Disfigured dismantles ableism in fairy tales and makes it fun

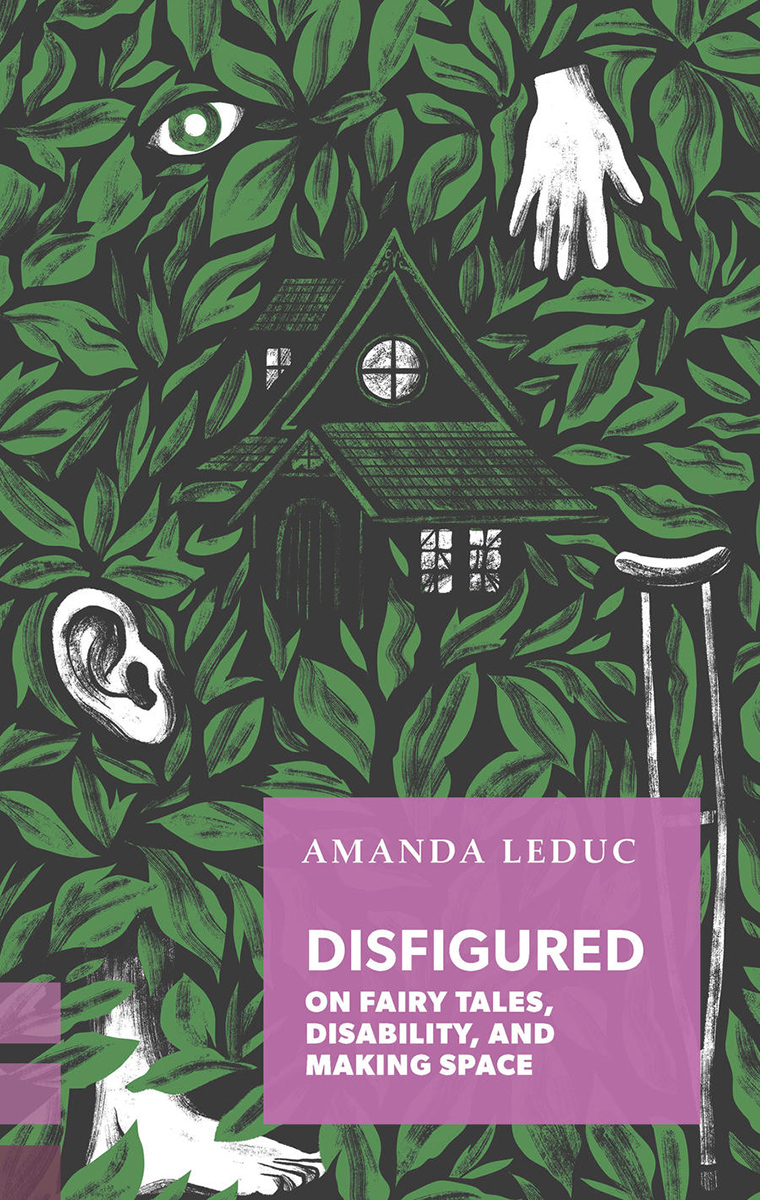

Amanda Leduc offers a stunning criticism of the ableism in fairy tales with her autobiographical book Disfigured, released earlier this year. After taking a stroll in the forest with a walking stick, Leduc struck inspiration and began to make connections between the fairy tales she loved as a child and her experiences as a person with cerebral palsy.

What’s charming about Disfigured is that it’s not written by an academic who specializes in folklore, and Leduc avoids complicated or technical jargon. The book makes it clear it’s more of an autobiography than it is a fact-filled non-fiction piece. Instead, it appeals to the youth in us all, capturing what children who grew up with Disney loved about the movies instead of focusing on archetypes or abstract symbolism. That’s not to say it doesn’t satisfy a craving for psychoanalysis of stories, however, as Leduc ties in quotes from field experts to present a well-rounded argument to her readers.

Disfigured reads almost like a love story to Leduc’s younger self — a whimsical but physically awkward girl who fantasizes about one day looking beautiful in a white wedding dress, but unable to incorporate a wheelchair or crutches into that dream. Interspersed between the history of fairy tales from a range of cultures and the recounting of individual stories are memories from Leduc’s childhood. These almost-mournfully described flashbacks are where the book shines, offering a pathos that’s extremely effective. They give an emotional sense of how fairy tales are innocently able to influence children into associating characteristics like ugly, deformed, or disabled with characters who are evil or who are transformed to become beautiful in a happy ending.

Disney is also heavily criticized — which is both expected and appreciated — for its subtle but nonetheless damaging incorporation of ableism. Scar from The Lion King is a character who’s based entirely on his disfigurement. The Hunchback of Notre Dame leaves Quasimodo with friends, but not love, and exploits him for “inspiration porn” — a term to describe the condescending phenomenon of inferring that those with disabilities who meet lower expectations than able-bodied people are huge sources of inspiration. Leduc’s childhood favourite, The Little Mermaid, made her retroactively realize that she related more to Ariel as a mermaid than as a beautiful princess who could walk on land with ease. For a little girl with cerebral palsy, though, there was no Ursula to strike a deal with or magical transformation that took place — for Leduc to gain her legs she had to undergo surgery and therapy.

Most importantly, this book is an eye-opener for able-bodied readers everywhere. It describes disability rhetoric and sets a good foundation for anyone wanting to become a better ally for those with disabilities. It sets down a broad and working definition for ableism from scholar Talila A. Lewis as “a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, and excellence.” The book also contrasts the medical and the social models for disabilities. Leduc helps readers imagine a future where we can accept differences in others without judgement, instead greeting them with a willingness to accommodate so everyone can function optimally in society.

Disfigured rejoices in the nostalgia and love of childhood fairy tales while also questioning their use of a binary: if you’re good, you’re a handsome hero or a beautiful princess, and if you’re bad, you’re the ugly stepmother, a hag, or a sorceress. It does so while effortlessly weaving in stories from the author’s childhood to show that they weren’t just stories; they became internalized for many children. This autobiography offers a fresh perspective on age-old tales, encouraging readers to question what they know about disability and to learn something new about stories they thought they knew through and through.

Chandy is a biology major/chemistry minor who's been a staff writer, Arts editor, and Managing Editor at The Cascade. She began writing in elementary school when she produced Tamagotchi fanfiction to show her peers at school -- she now lives in fear that this may have been her creative peak.