By Michael Scoular (Contributor) – Email

Print Edition: October 1, 2014

The Princess of France

(La princesa de Francia)

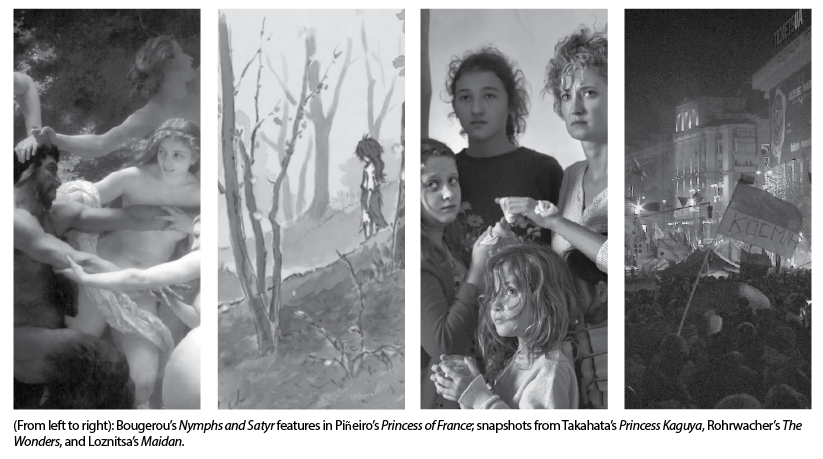

An adaptation of Love’s Labour Lost by Argentinian director Matias Piñeiro (his third Shakespeare re-working in a row), The Princess of France has a grand, exciting opening that involves a radio song request, an evening game of football, and a merging of the two into elevated normalcy — a mode Piñeiro uses rather than a proscenium arch. His style of adaptation is to evoke the feeling of Shakespeare’s work — the endless wordplay, using screen entrances and exits to mix up already complicated relationships, and the mistakenly exchanged objects and letters that reveal or destroy hidden desires — rather than having his characters speak the playwright’s language (though a radio performance of the play does figure into the plot). Piñeiro’s narrative tricks (dreams, perspective shifts, jump cuts) and the cast’s youthful exuberance sometimes give off the sense of early Godard (minus the politics), where a complete understanding of the movie’s humour, freedom, and excitement seems impossible without knowing the speakers’ language and how it is being stretched to the point of breaking.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya

In its middle portion, The Tale of Princess Kaguya approximates the last-act trickery of the same play Piñeiro draws on (gifts, masks, and the significance of saying “no”). But it’s more notable for representing the end of a remarkable era, as was The Wind Rises, which was released in Canada earlier this year. With these two final films from the primary directors at Studio Ghibli, the animation studio will be suspending the creation of any new productions. What it will look like on the other side is unknown — a summary of a news conference incorrectly translated as saying the studio was done for was so believable it took a Variety story to counter the claim. But not only is hand-drawn animation an endangered form (Pixar’s attempt to approximate the style two years ago was simply hideous), so too is the studio’s expressive qualities. The idea that there is a personal perspective on the world behind a Miyazaki (or in this case, Takahata) film seems, at least in American animation, to be virtually non-existent.

With Princess Kaguya, the sense that this is a late work, fixated on mortality as much as bold expressivity, is unavoidable; it complicates what is, for much of the first half of the film, a fairly standard fairy-tale adaptation. Like Takahata’s My Neighbors the Yamadas, the animation style is distinct from most of Studio Ghibli’s productions. Watercolours trail off into the horizon, and charcoal strokes provide basic outlines, or, in one moment of complete abandon, pure abstraction. Princess Kaguya engages with traditional forms of animation and custom only to upset them. It is both familiar to those who have seen other Ghibli protagonists admirably stare down societal rules, and surprising to see them come out of animation — similar to the melancholy poetry of Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, but in a way that completely diverges from that example by the end. Together, the works are complementary, but apart, Princess Kaguya seems more profoundly disquieting, a complete-arc epic to Miyazaki’s art-and-war historical essay.

The Wonders

(Le meraviglie)

This year’s winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes might look modest. Its plot is centred on the threat of industry regulations on a rural bee-farming family as well as a reality TV competition, and is light on dramatic incident. What is there has little purpose beyond emphasizing the separation in perspective between the family patriarch, Wolfgang (Sam Louvyck), and the oldest of four daughters, Gelsomina (Alexandra Lungu).

Director Alice Rohrwacher has made not so much a coming-of-age tale, but a film, shot in 16mm, that inhabits the experience of wanting to be over with coming of age while being “too inside things,” as one character puts it, to know where the process would begin or end. In other words, it’s a great teen movie, with pop songs, the attraction slash repulsion of adulthood, and the relationships between sisters (and mother figures) all filling in detail in ways a more impressive plot would not.

The prize at Cannes came from a jury headed by Jane Campion. While it would be reductive to say the two filmmakers are on the same wavelength in The Wonders as in The Piano or Top of the Lake, so much of each performance of the cast comes out of the actors reacting to and moving through their physical environment — in this case, doing the actual work of coralling bees and extracting honey — but in a way that does not reduce them to figures in a landscape or diminish their emotional and social character.

Maidan

Sergei Loznitsa’s documentary of this year’s Ukrainian revolution opens with a landscape of human faces filling the frame, many turned upward to sing their national anthem. While images from the protests were spread across Twitter and in international news reports, Loznitsa’s documentary gives form to the experience of protest. Maidan is not full of context, nor does it pose itself as an exhaustive account of the revolution: one of the work’s few title cards calls this “the story of…” what happened in Maidan.

Social media makes us more aware of worldwide movements in a way traditional news channels never could. This week we see tens of thousands occupying Hong Kong’s city centre, following violent student-police confrontations months ago in Taiwan, calling for democracy. Meanwhile Ferguson, Missouri remains a confrontation of racist police brutality, and countless developments from earlier this year will not get a fraction of the time or timeline space with everything constantly updated and scrolled through. In contrast, the act of photography becomes a way to slow things down.

Loznitsa’s approach is formally controlled: a static mounted camera, holding shots for minutes at a time, allowing protesters to drift past toward a centre stage. There, church representatives, speeches, and updates are sent over loudspeaker before violence visits Maidan, and the stage becomes a background voice for injury updates and calls for support. Many protesters were taking photos of their own, joining in song, or listening to poetry. The camera, set just above eye level, captures deep compositions of nationalist protest (the anthem as rallying point takes on new meaning for people looking to reclaim Ukraine) so full they transcend a comparison with Brueghel, in whose work the eye is unable to take in everything but finds scenes in the margins of the frame as much as at the centre.

Maidan is the type of work that will outlive its festival setting and awards, living as historical document and war photography. Where mass media generalizes, artists find specificity.