Print Edition: January 15, 2014

8. The Dilettantes by Michael Hingston

It’s obvious why this title landed here. The book is about SFU’s student run paper the Peak, but that’s not the only reason we’re into into it. The Dilettantes captures what it’s like to be a student in the Lower Mainland of B.C. Not since Neal Stepson’s The Big U — another first book by a great author — have we been able to kick back for a quick comical read about the realities of university life. Its ironic look at academic life will have you quoting lines during your next classroom debate. Hingston wrote this for students, not for book reviewers. National reviews of this book have been unfair by missing the target audience. Read it. — C.D.

7. After Visiting Friends: A Son’s Story by Michael Hainey

This was my absolute favourite book this year, possibly because I also work for a newspaper. In short, Hainey goes in search of the truth behind his father’s unexpected death by heart attack 20 years ago. The newspapers blandly report Bob Hainey died “after visiting friends,” but he was a newspaperman, so it’s more than possible that other journalists are covering something up to take care of their own. Michael’s search takes him across the country, and ultimately ends with a question: does knowing the truth change anything at all? And if it does, was it worth it? — D.B.

6. Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

This is possibly the weirdest historical fiction you will ever, ever read. I hated the first two chapters, because it wasn’t until the third chapter that things started really falling into place — in short, our protagonist Ursula Todd restarts at the beginning of life every time she dies, and is implanted with the innate sense of how to avoid making the same mistakes again. It’s like watching someone read through a choose-your-own adventure and begin again and again and again, following different variations each time. The cherry on the cake: you know how hypothetically time travellers always talk about going back in time to kill Hitler? That’s a thing. But can she pull it off. — D.B.

5. Canadian Foreign Policy in Africa: Regional Approaches to Peace, Security, and Development by Edward Akuffo

Putting a formal political science book on this list is totally pretentious. Yes, the book is dry. Yes, it’s academic. Yes, reading about foreign policy — along with all of the genre’s acronyms — puts most of us to sleep. And yes, the book costs way too much: around $100. But until Akuffo’s work there hasn’t been a single book completely dedicated to the topic. The content spearheads a new exploration in international relations, looking to reframe issues like security and development. Too often Canadian scholars rely on the United States to crack the question of peace, order, and good governance in Africa. We have our own political science scholars that can untangle the problem, too. — C.D.

4. Who Owns the Future? by Jaron Lanier

A lot of people are worried about what the internet is doing to our literacy and economy, but few people try to come up with real solutions. What do you do when new technologies like Instagram replace the Kodak factories that used to employ thousands of people? This powerful missive explores the dark side of technology fthrough lessons Lanier learned as the father of virtual reality in Silicon Valley. It cracks our ideological beliefs about what we can do for technology and what technology does to us. Digital technology has the same trade-offs and limitations analog has always had. — C.D.

3. Worst. Person. Ever. by Douglas Coupland

Douglas Coupland’s latest novel is perfect if you’re looking for an asshole. Raymond Gunt (who I will loosely label as the protagonist) is perhaps the biggest asshole you will ever meet. To be let into his mind for 317 pages is disgusting, revolting — and enlightening. His callous selfishness and general wolfishness makes the reader take a step back and consider not only how rude the rule is getting as a whole, but what that means. Are goodness and rudeness mutually exclusive? On a non-philosophical note, it’s cathartic to watch a jerk say exactly what you wish you could to screaming babies and sexy women, and then get exactly what’s coming to him for other miscellaneous everyday asshole-ishness. — D.B.

2. The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America by Thomas King

Thomas King has been called the “Canadian Mark Twain.” His latest book is a crash course in the historical catastrophe of North American First Nations peoples’ relationship with settlers. But this book isn’t the dry, recycled tale you keep hearing about. King has one foot in the past and another in the present; every story in the book is linked and contextualized to the issues of today. King’s sentences are loaded with heavy comical punches that land critical blows on both sides. Humorous, loveable, and above all: full of truth. — C.D.

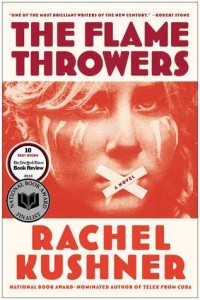

1. The Flamethowers by Rachel Kushner

The star of this book isn’t a character (although they’re also strong and intriguing), but Kushner’s prose: her descriptions and phrasing wrap the reader up like a silk scarf — strong, soft, and comforting. It takes place in the ‘70s, when there was still a scent of newness to now-nostalgic ideas: the characters ride motorcycles before they are cool, are part of the New York art scene before it becomes pretentious, and take part in the Italian revolution before mass media made political uprisings seem commonplace. The theme of aesthetics versus violence stays true today, and the flashback to a long-gone era comes with an ache of nostalgia for a time when things were simpler, even though they never were simple in the first place. — D.B.