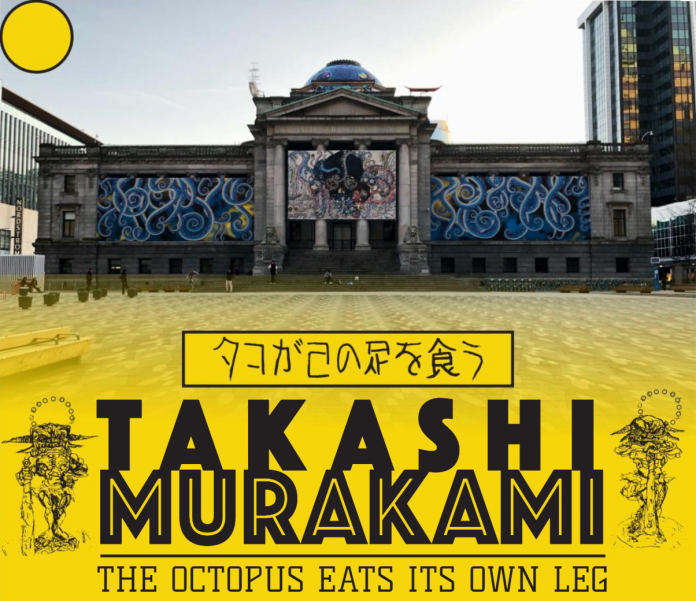

Upon entering the second floor of the Vancouver Art Gallery, a gold leaf wall with the mega black title: The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg marks the threshold of the journey through the oeuvre of artist Takashi Murakami we viewers are about embark on. The exhibition marks the first retrospective in Canada for the artist as the works presented span the past 40 years of his career.

Upon entering the second floor of the Vancouver Art Gallery, a gold leaf wall with the mega black title: The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg marks the threshold of the journey through the oeuvre of artist Takashi Murakami we viewers are about embark on. The exhibition marks the first retrospective in Canada for the artist as the works presented span the past 40 years of his career.

The first few works of Murakami’s exhibition are not the anime-esque design which is advertised in the murals around the exterior of the gallery. Instead, there are four muted, traditionally painted rice paper canvases which study the movement of a turtle.

Then, across the room from the turtle studies is a massive 10-by-25-foot swirling blue multi-panel mural done in the style of Nihonga painting, which Murakami has a PhD in. Nihonga is a type of Japanese painting done on rice paper which uses mineral powders to create vibrant, uniformly-coloured paints. The subtle variations in the colour are mesmerizing. The journey through his works begins awash in a sea of blue — the curator is telling viewers that Murakami’s seemingly lighthearted works are not to be mistaken as kitsch; he has a PhD, and the art history chops to prove it.

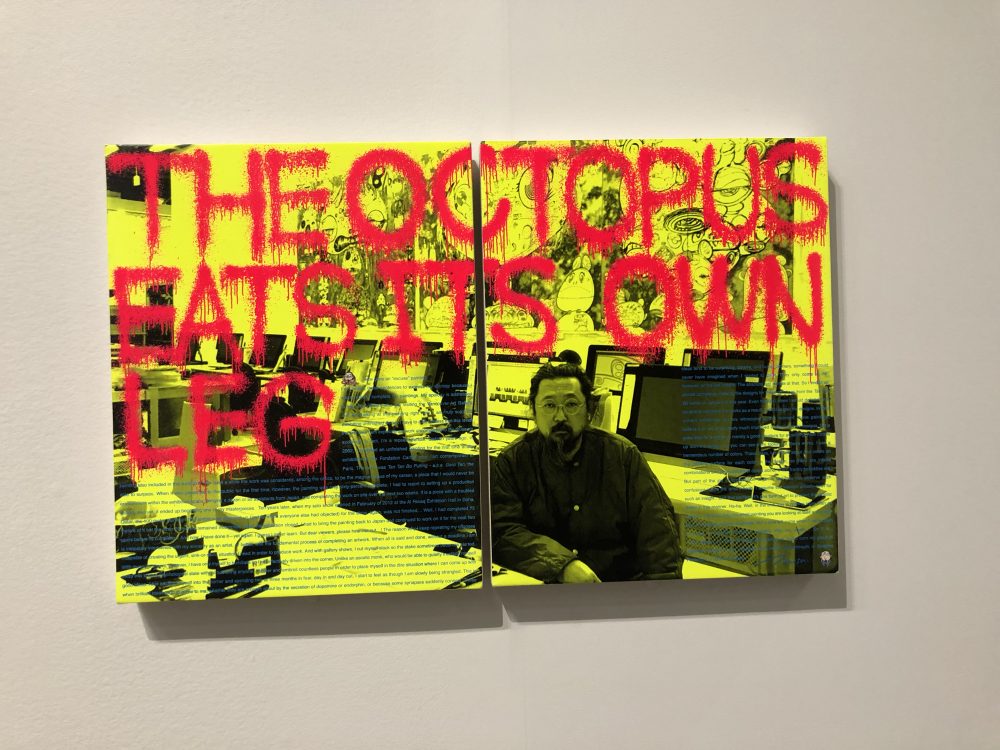

Around the first bend, we‘re introduced to Mr. DOB. Murakami designed the character to act as a logo for his studio, but also to be a self-portrait and means of self-expression by way of an alter ego. Mr. DOB appears in most of Murakami’s work from this point on, appearing in various distorted, altered, and multiplied forms. In one of the videos paired with the exhibition, Murakami notes how Mr. DOB reflects his mental and emotional state when it appears in his works. The thing that will strike viewers the most is Murakami’s openness and honesty about his personal struggles with creating art, and his crippling social anxiety. This becomes most clear in the way the curator pairs the introduction of Mr. DOB five feet across the hall from a small painting of a photo of the artist in his studio with a letter written by him stroked over it — a personal note before we enter the first room of the Murakami spectacle as advertised.

The work is titled The Tragicomedy of a Painter Living Day in and Day Out in His Studio Haunted By Deadlines (2018), and relays an apology/excuse from the artist as to why a few of his paintings are exhibited unfinished. He acknowledges his creative strategy is to set himself deadlines which he cannot miss, and then wait till the very last minute to develop the design, spending day after day in fear till he feels like someone is slowly strangling him. He says this feeling tends to evoke brilliant, surprising, and bizarre ideas — this is why some of the paintings are not yet completed.

Murakami’s honesty seems to tie in strongly with the note on the front wall regarding the meaning of the phrase, “the octopus eats its own leg.” Interestingly, the title is itself a meaning — it is the English translation of a Japanese phrase which means to sacrifice or feed on oneself to survive in hard times. This is in reference to how an octopus will eats its own leg for nourishment to avoid starvation, but does so knowing the leg will grow back. The gallery was titled with the interpretation of the phrase because of the significance of this procedure to the way Murakami runs his practice.

His openness about his struggles really brings him from the level of an untouchable master artist to a fellow creator wracked with his own set of deficiencies. This maybe has a lot to do with the art theory and style that he created and works in.

In the great room across from his self-portrait and note, we finally begin to see traces of the style which Murakami is best known for. His theory of art, one he calls Superflat, is made up of vector-like designs filled with restricted tones from a restricted colour palette. His style seems to be heavily influenced by anime and manga, but the core concept of it is actually birthed from classical Japanese paintings in which bright colour accentuations burst out from refined, simple images and designs. The works on each wall of this great room all depict psychedelic distortions of the aforementioned Mr. DOB in some form or another, insinuating Murakami’s personal connection once again to the works.

In one of the videos in a corner nook of the gallery, Murakami muses over how comic writers are in some way the highest level in Japanese society, because of their influence over otaku (obsessive collectors and fans of anime and manga), and their ability to drive the economy. He copies the style of these artists to harken on their work and its power while also appropriating classical Japanese art traditions. He folds the two together to tear down the boundaries of high and low society, as well as the traditional ideas of low, high, and commercial art.

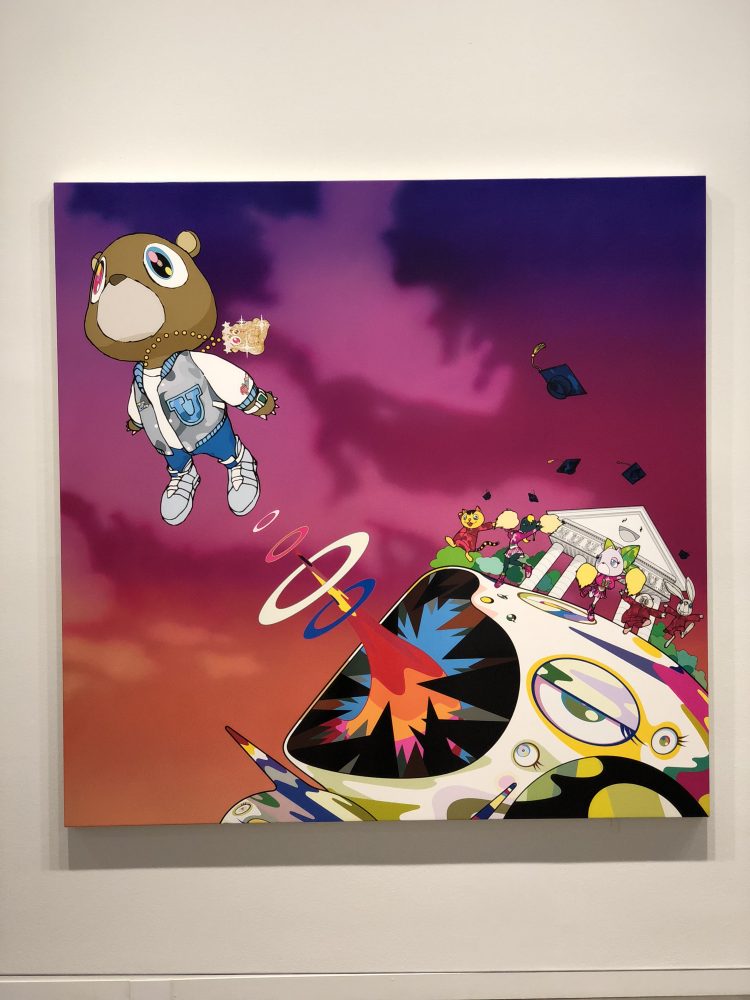

This breaking of boundaries becomes most clear when passing Murakami’s Kanye album covers. The commercially made and financed album cover paintings are displayed alongside all of his other non-commercial “high art” works with no distinction. This is exactly what Murakami’s Superflat theory intends to do — to flatten out the lines between commercial and non-commercial art, to bring together current and historical art practices, to remove social structures, and to put himself into his work.

His artistic practice as well is one that, like Warhol and other prolific artists of the past, brings question to the involvement of the artist in the artwork, and thus the intrinsic value of the work. He begins with a small sketch which he hands off to an assistant who digitizes it, enlarges it, and then refines it. It goes through revisions, and then is handed off to assistants to plan onto a canvas, and then paint or silkscreen under Murakami’s supervision. This process is much the same as the many commercial graphic design, architecture, film, and photo studios around today. A single owner or several partners have a firm and sponsor assistants and apprentices to carry out their ideas and works which they supervise and then deliver to clients.

The way I see it, Murakami’s moves to blur lines paired with his studio procedures emphasizes how he is an example of the rebirth of the studios and artists’ workshops of the past. If we’re honest, Apple is the Medici family of our time, sponsoring contemporary directors like Spike Jonze to direct their commercials, and licensing up-and-coming musicians’ music for their ads.

This is the same process as the days of high art from the past. Wealthy families pay artists to record their images and stories, and to create entertainment for them. Corporations, essentially the modern class which holds most of the wealth now, sponsor artists to make the works that will position them well with the consumer.

This is the same process as the days of high art from the past. Wealthy families pay artists to record their images and stories, and to create entertainment for them. Corporations, essentially the modern class which holds most of the wealth now, sponsor artists to make the works that will position them well with the consumer.

Murakami takes this legacy on, and presents it as one where art can regain its value and functionality in a modern society. His toys and merchandise are only an extension of this process of taking down the boundaries between prestigious elite art and commodity for the masses.

All in all, this exhibition demonstrates extreme care in modelling itself after the way Murakami slowly revealed himself in his works over the years. The journey through the show presents the viewer with a nuanced look at all of his periods of work, but also at the struggle and emotion that he sincerely imbues each work with.