A Trip Through Time

She wipes the grime off of her forehead with the back of her hand. When she’d entered the chamber it was cool — slightly cooler than then the crisp summer air beyond the narrow corridor — but now it was stifling in the dim, hollow space. She peers through the torchlight; her breathing is heavy. She’s been awake for days, and though exhausted, her body feels light and buzzing like an insect. She imagines she can fly, if only she had wings to carry her off.

One of the elders holds a bundle of dried plants to the solitary flame in the center of the wide, squat chamber. It’s difficult to make out the figure, adorned in ceremonial dress that obscures her features, and the air is thick with sweat, smoke, and shadow. The herb bundle produces a fragrant, cleansing aroma, a sign that the ritual is complete. How well she performed was still in question, but she followed the rites exactly, and her long vigil has come to an end.

Another figure approaches with an offering of water. She gingerly lowers herself onto a deer-skin that has been laid out on the cold earth, and crosses her legs before gratefully accepting. She recognizes her sister by her stature, for she is younger and much shorter than the others, apart from her grandmother who is too old for the ritual now. Those not directly involved, such as her mate and their children, are waiting outside, guarding this sacred place. The water runs down her throat like the first seasonal rains into a dry creek bed. It feels like renewal, and she tips her head back, water overflowing her lips and running in muddy streaks down her dusty chin and onto her exposed body. She is the only one nude, for there can be nothing obscuring the bond between her and her ancestors.

Her eyes scan the curved walls and domed ceiling of the dark chamber. She’s been here many times before — participated in the ritual many times before — but never like this. The familiar recesses in the walls appear to have taken on an unfamiliar quality and she finds it disquieting that she had never seen it this way before. Her gaze lingers on one of the alcoves, and on the skull placed gently within it. Then, her eyes drift to the recess above it, which sits empty. A spot reserved for her, someday.

It should have been her brother, but he tragically died in the winter chill before he could retrieve the bones of their father from the resting grounds to transport them here to rejoin the clan. It was then that the responsibility passed to her. Only those who complete the ritual, as she just had, can find their way back here after death. Many generations now lined the sacred walls of this place, protecting the great line’s future. The rest of her people, once returned to the earth, may watch and guide, but can do little more. She can feel them watching now.

She hears a call from outside, and the sound echoes and pulses around the smooth, pocketed walls. It’s time. She rises to her feet and makes her way to the narrow tunnel that serves as the entrance to the chamber. She’s an imposing figure, and has to make herself small to navigate the passage. She can see the sky beyond the aperture of the cavern. It’s a deep, ocean blue. She brushes her hands against the rocky pillars that support a massive capstone which marks and guards the entrance. Ducking under the stoney roof, she emerges, and her mate drapes a skin around her shoulders. She is still damp with sweat, and her skin contracts in goosebumps against the chill. He brushes a few strands of hair from her face and tucks them behind her ear before gesturing for her to turn around.

The highground of their summer encampment gradually slopes down, running into the shoreline of a narrow inlet where the family has fished since the last of the ices melted from this place long before she was born. Beyond the waters, past the far shore, two large mountains rise up, piercing the sky with white-capped peaks and sheer rocky cliffs. She watches the snowcaps shift to a pale pink. This is the moment of truth.

She sits with her back against an elm tree, warm in her furs, belly full of smoked meat and berries. The sky is streaked with high wisps of mist streaked with fire and fringed with gold. A low puff of cloud rings the tallest mountain peak, which pierces the haze to meet the luminous heavens. The sea, calm and placid, glimmers in the dawn like earthen starlight. On this day — the longest of the year — she has completed a once-in-a-lifetime ritual, and she has performed it well. Her ancestors have deemed it so. Secure in this, she lets her weariness take her, and falls asleep, dozing in the shade of eternity.

The Problem of Imagination

As much as we might like to tell ourselves otherwise, human beings are not separate from nature. Yes, we have come to construct our habitats rather than bivouacking in caves, but so do beavers and bees, and we don’t see them as apart from the natural world. Indeed, the worlds we create are often ideal for other species. Raccoons, foxes, rats, birds, and insects often thrive in urban environments where food is abundant and apex predators are few. These animals are typically regarded as pests precisely because they’ve adapted so well to what is supposed to be our world. Who the hell do they think they are, after all?

The human impulse to create a barrier between ourselves and an often unforgiving environment is understandable. We lack strong defenses like thick hides, or sharp talons to ward off predators. To venture into the wild places of the world can mean encountering Tennyson’s “nature, red in tooth and claw.” It can be frightening, and anxiety-producing. When we hear that large predators have wandered too far into human spaces, we often take action to remove them — in one way or another. Even if we venture into their habitats, like the ocean, and tragically become prey, we react as if the animals have declared war. In Sydney, a fatal, unprovoked shark attack (their first since 1963) led to calls for a culling.

The disconnect is that while our evolutionary biology tells us to fear the bat that swoops too close to our head, our technology has radically changed our relationship to the rest of nature. The saying, “it’s more afraid of you than you are of it,” has never been more rational. We have provided animals with many good reasons to fear us. Sure, we kill to sustain ourselves, as many animals do, but we also kill out of malice, greed, boredom, or simple disregard.

We drive species into extinction all the time. Often we don’t even realize we’ve done it until it’s too late — but other times, we’re all too aware — as the novelty of a species’ fleeting existence increases its market value. We wipe our species because we’re careless, like introducing pigs or rats to remote islands. (If you want to have your heart broken, listen to John Green talk about the Kaua’i o o on his podcast, The Anthropocene Reviewed.) Sometimes we wipe out whole ecosystems for farmland or plantations, or pave a road through their home and remove the critters one at a time with our Michellins and our Jeeps. We see the devastation, but then swipe to the next video — a skater crushing his nuts on a rail — and the world is put right again.

Even though our primitive need for abundance and security is well understood, and despite the obvious destruction we leave in our collective wake, we can’t seem to shake ourselves from the patterns that pervert our ability to live in concert with the rest of the world’s inhabitants. We’re like a good friend who doles out the very best advice, and yet applies none of it to our own lives. Whether it’s carbon in the atmosphere, poison in the water, or desolation on the land, we look at the rest of the world and wag our finger, and then use that same appendage to order a shirt that will ultimately find its way to a Guatemalan river; or we unnecessarily upgrade our cell phone with a lithium battery mined from the Congo rainforest, to repost an Orangutan fighting off a digger “destroying its jungle home” in Borneo. A sight like that is enough to make you side with Thanos.

We do know better. We’re not an inherently evil species. So why, with all our wisdom and knowledge, can we not escape the pull of primal impulses that create so much collateral damage? Is the answer to be found in more data, logic, and rationality? Maybe it’s to be found in the recesses of our past — in another persistent and universal instinct.

My Dog, the Dreamer

My dog, much like his owner, has an affinity for sunsets. Every evening, whether the skies are brilliant hues or shrouded in brooding clouds, he perches atop our sofa and surveys his street. From this vantage point, he silently bids farewell to the neighborhood.

As the sun sets on the town below, my furry friend becomes a solitary philosopher, lost in his own musings. He watches the world transform from day to night, a ritual as reliable as the moonrise. I cherish these moments, observing him in his sunset reverie. Sometimes, he turns to me, as if to say, You see this, right? It’s a nonverbal acknowledgment — a shared sentiment between two beings with a history that spans millennia.

In the grand tapestry of human evolution, there exists a span of time when our distant forebears made the profound leap from instinctual beings, concerned solely with the immediacy of food, shelter, and survival, to creatures capable of contemplating the future. It’s a mystery that unfurled over millions of years — a transformation that reshaped our perceptions and redefined our very nature.

We, the descendants of those early visionaries, once gazed through tall grasses and dense forests, always on the lookout for what lay around the next obstacle. But as landscapes shifted, we adapted. To survive, we had to see danger before it arrived, and so, we stood upright and set our sights on the horizon. We became tall to gaze into the distance, beyond the veil of the immediate.

Our ancestors began to imagine the bounty and peril that could await them over each new horizon. The prospect of a grove of trees brimming with fruit, the presence of a herd, or the lurking shadow of a predator — all these uncertainties required foresight, predictions, and strategic planning. We learned to thrive by forming communities, relying on numbers, and devising ways to organize our societies. Was it the relentless pursuit of the future — the eternal fixation on the next frontier — that laid the foundation for the consciousness we hold today?

As I sit here, sharing this moment with my dog, absorbing the beauty of the skyline together, I’m reminded of the enduring bond we share — that our species share. He, too, looks out to the future, acknowledging the close of another day. Dusk fallen, he crawls closer, patiently awaiting an invitation to nestle in my lap. It’s a legacy, a connection that stretches back over 30,000 years — a testament to the intertwined destinies of two species that recognized the potential of linking their fates together.

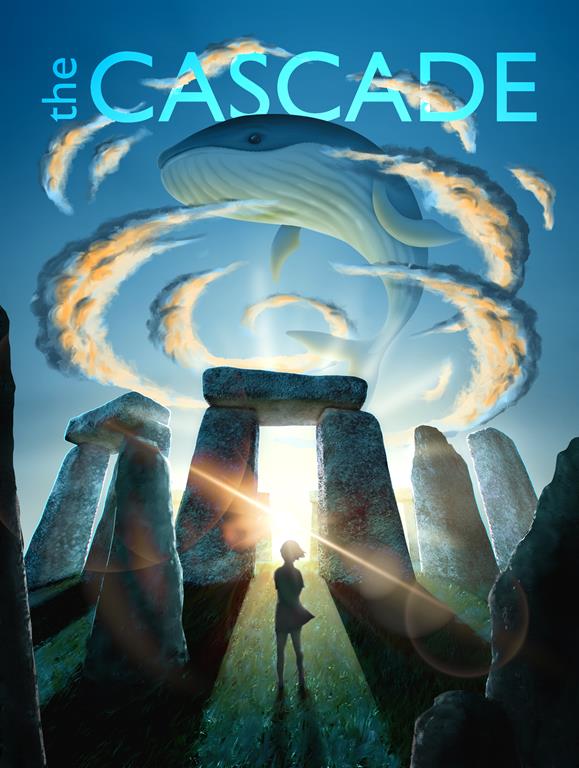

A Bit about Megaliths

Megalith is not a common term, but after explaining that it simply translates to large rock, and refers to human-made stone structures, the first image that pops into people’s mind is usually Stonehenge in England, or perhaps the infamous Moai of Easter Island. Truly, those are fantastic examples of megalithic structures, but megaliths pop up all over the globe and date from the prehistoric to the present day. Apparently there is something in the human condition that tells us we can wrest a sliver of immortality from the earth to mark our brief existence on it.

Megaliths often correlate with loosely agricultural societies — people who are cultivating crops and domesticating animals, but haven’t fully stratified into specialized groups of warriors, builders, and artisans — but even this is difficult to ascertain. Megaliths, like the societies who erect them, come in many variations. They also serve a variety of functions. Some mark tombs, while others serve as meeting places. They are meant to be a mark upon the landscape, so indelible that they become the landscape. The stones can be transported for hundreds of miles, or used where they are found, as with glacial erratics, carried from afar and deposited after the ice recedes. Many of the deeply personal meanings of these sites have been lost to time, their messages buried with their builders and caretakers, save one: we were here.

The dates and arrangements of megaliths tells us a little about their purposes. Some appear to come at the end of a sustained period of inhabitation, turning the location into, in the words of Julian Thomas, professor of archaeology at the University of Manchester, “places of memory.” Thomas discusses the mysterious meanings of megaliths on the BBC Radio podcast, In Our Time. He explains that while some megaliths are in “conspicuous” locations, like prominent hillsides or along “natural routeways” to ensure that they will be seen, others turn things around to have “commanding views” — of coastlines, cliffs, rivers, or mountains.

In the same conversation, Susan Greaney, lecturer in archaeology at the University of Exeter, mentions that scholars are taking a closer look at how these structures are situated within the landscape. “We get monuments,” says Greaney, “where particular clefts in mountain ranges nearby, or particular viewpoints of distinctive hilltops are deliberately showcased from the monuments in relation to the movement of the sun.” It’s not a stretch to think that some of these sites were places of ritual, connection, and spirituality. Religious traditions in cultures without the written word often draw heavily from the environment and the natural world.

“It’s very likely that you don’t have an idea of different realms,” says Thomas, “like heaven or hell or an underworld. Instead, I think it’s likely that spirits, deities, and ancestors are understood as being imminent in the landscape. When people are actually constructing these monuments and reorganizing the landscape, it’s as if they’re engineering the cosmology.” Thomas thinks that these sites could be places of profound meaning, especially those with hidden chambers. “Being inside these monuments is going to be quite an experience.”

Researchers have studied the acoustics of prehistoric chambers around the world, and found a recurring characteristic: they resonate with particular frequencies that induce physical and cognitive effects on the human brain. Specifically, deep male voices attuned to 70Hz and 114Hz echo and compound in the “super-acoustic” rooms. During experiments, volunteers exposed to these frequencies tend to experience altered states of consciousness, signaling that these could have been transcendent events. “You’re entering into a dark space covered over,” says Thomas. “You crawl down a low passage or crouch, and then you open out into a big open area where you’re encountering the remains of the dead. All of this I think is going to be an almost overwhelming experience.” Some might call it Sublime.

Encounters with the Sublime

“I laid on a log in front of my camp for the night and cried, watching the sunset,” wrote Katie Purdey, recounting in an email her recent solo trip to Juan de Fuca Provincial Park. “The tears came from a deep sense of relief and realization that life could be more simple than I was making it out to be.”

Curious about the deep-seated connections between human beings and our environment, I asked Purdey, a UFV alumna, what drives her to regularly get out into nature, and just what it is she gains from the experience. She replied that getting off the grid acts as a “form of release. It’s a way to off-load the external pressures of day-to-day life, and to sort through the noise in my mind.” As a coach with a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology, Purdey understands the importance of health — body, mind, and soul. “When I decide to go out for a hike, run, or adventure of any kind, I make a commitment to set aside that time to be present with myself and my surroundings. It’s a way of slowing down, and a way of coming back to a more centered way of living.” But it wasn’t always this way.

“My relationship to the environment has changed substantially over the years,” says Purdey. “As I spend more time exploring the outdoors, I’ve developed a greater appreciation for the natural beauty it holds and make stronger efforts to support the well-being and integrity of the habitats around me.” It’s far from a universal ethic. Nature and wilderness tend to evoke contrasting emotions — a dichotomy embodied in the depiction of “the woods” in the stories we tell. Forests serve as the setting for many of our fairy tales, and embody the mysterious and unknown. They often conceal threats which appear in animal, human, or supernatural varieties. However, they also shelter oases: picturesque cabins, sunny glades, and benevolent creatures who can provide care, respite, and aid to lost travelers. For as long as we have been constructing barriers between human societies and the wilds, we have been longing to reinforce that ailing connection.

In the early 1980’s, in response to widespread burnout and stress-related illness, the practice of shinrin-yoku emerged in Japan. Translated as “forest bathing” or “taking in the forest atmosphere,” the objective was to immerse yourself in nature, allowing your senses to fully absorb your surroundings, and reconnect with the environment. Unlike a hike or nature walk, forest bathing is about slowing down and realigning with a more natural pace, and contains many of the same elements as meditation and mindfulness. The benefits aren’t just anecdotal. A 2019 study found that “Forest bathing activities may significantly improve people’s physical and psychological health.” Amazingly, the researchers found that the practice demonstrated an ability to “regulate blood pressure, reduce blood glucose, regulate endocrine activity, relieve mental disorders, fight cancer, boost immunity, and treat respiratory diseases.”

The benefits from sojourns into nature aren’t limited to those that arise from tranquil relaxation. According to a 2018 study, researchers found that feelings of awe correlate with increased feelings of humility — a core virtue that works against narcissism, arrogance, and egoism. When we face the truly awesome: something that instills wonder, reverence, and terror in our hearts, our daily irritations and paltry ambitions lose their standing.

Both light and dark natures exist in the obscured hearts of the woods — as they do in people — which makes them a metaphor for our own inner natures. For wayfarers like Purdey, the experiences can be profound. “I’ve also had emotional reactions to certain animals crossing my path… they felt welcoming… as if they were sent as a sign.” She doesn’t always know what it’s supposed to mean, but that “it comes again, as a release. An unwavering sense of, `I am right where I need to be, and everything is going to be okay’.” In an increasingly urbanized world, many are finding the source of rejuvenation in our ever-dwindling wild places. It’s far from the first time.

Capturing the Sublime

“The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is astonishment: and astonishment is that state of the soul in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror.” — Edmund Burke

Whenever I get too close to the Stawamus Chief, a cold chill runs down my spine and I feel a creeping onset of unease. However, unlike those who summit it, where a healthy level of fear is warranted, my dread comes at the base of the mountain. It’s an odd feeling. As the sheer cliffside takes up more and more of my field of vision, my apprehension mounts. Sometimes I even need to steady myself when I crane my neck to take it all in. I know I’m in no danger, and yet my senses become overwhelmed at the monumental structure. This is the experience referred to as The Sublime.

“For Burke, it’s about a kind of aesthetic, or a psychological experience,” says Dr. Heather McAlpine, UFV’s English department head. “Prior to Burke, it was coined by Longinus or Pseudo-Longinus who was a kind of rhetorical authority in the classical period, and in that period of time, Sublime is used to talk about oratory — using language or using delivery that will uplift the listener … It’s a rhetorical term at the beginning, and then when Burke gets a hold of it, he kind of changes it a little bit around.”

I wanted to ask Dr. McAlpine, an associate professor of English with a keen interest in Romantic literature, to help me better understand the way that the human relationship with nature was changing in The Romantic Period. “The Sublime bridges the gap between the earlier 18th century enlightenment rationality and the Romantic period. We see The Sublime emerge at a time when the focus on rationality and science was kind of wearing thin on people. They were thinking, Okay, science is great and everything, but is it helping us live better lives? Is it helping us understand love or sociability?” At a time of increasing urbanization — in the heart of England’s Industrial Revolution — many began to regard the natural landscapes differently.

Increasingly, the wilds were seen and portrayed as sources of spiritual renewal and purity — a way of nourishing the soul. Mountain spires, roiling seas, and cascading waterfalls became powerful symbols, embodying a quasi-divinity of their own. In the words of Dr. Kristian Urstad on the podcast, The Wisdom Of, the subjective feeling we encounter is due to the perceived contrast between “these natural enormities, and how small and mortal it is that we are in comparison… The Sublime is the experience of natural beauty that makes us fear for our security and our existence. It’s the experience of a natural beauty so majestic that it invokes the perilous.”

“The Romantics were all about recording the movement of their own mind in these moments of experience,” says McAlpine, who devotes much of her scholarly work to how poetry in particular grapples with the task of expressing transcendent experiences. She notes that Burke in particular seems to be encouraging people to try to have these experiences; to test it for themselves. In that, Burke sounds like a psychonaut: someone exploring altered states of consciousness, aware of the limitations of language and art to convey the truly ineffable, and encouraging a more personal exploration.

And explore, they did. Writers and artists trekked through the countryside in search of earthly inspiration, attempting to communicate to their audiences the upwelling of emotion they felt. Culturally, it altered the relationship with the land, and the objects they found there, as seen in a 2013 study. In the words of the study’s author, Kate Mees, the thousands of megalithic structures dotting the British Isles came to represent an important link to the past, “provoking contemplation and serving as memento mori” (a reminder of death’s inevitability). Mees contends that this “re-evaluation of prehistoric monuments” was associated with Romanticism, was “indebted to the taste for the picturesque and the sublime,” and “offered a sensory point of reference to the past.”

This new depiction even stimulated tourism. Ancient stone structures became “part of planned walks in order to encourage the contemplation of past civilizations (…) Ruins could raise the imagination and their presence could stand for a number of values, as reminders of the power of time and the ultimate fragility of human endeavour.” Much as the Romantic poets and painters were trying to replicate the sublime through their works, British estate owners in the 18th century began incorporating “prehistoric remains, either genuine or artificial,” into their designs. But the sublime is just a word, imperfect as it is, for the subjective experience we feel in the presence of something that forces us to face our diminutive existence. Can that truly be captured and conveyed, or is something fundamental being lost in translation?

Conserve only the Beauty

In 1851, when the world was still heavily reliant on whale oil for illumination and machinery lubricant, Hermann Melville published Moby Dick. The tale follows the exploits of the crew of the Pequod, a whaling vessel captained by the single-minded Captain Ahab in his dogged pursuit of the great white whale who took his leg. Moby Dick, a massive sperm whale, is a symbol of the sublime for both the reader, and for some of the ship’s crew. He’s depicted almost like a demigod: a whale greater and more terrible than all others, and the ruination of the ship’s crew comes from attempting to capture and kill something genuinely awe-inspiring.

Ishmael, the story’s narrator, tries and struggles in vain to express what it means to be in the presence of Moby Dick, but ties himself in knots, wrestling with the whale’s vast whiteness — a quality that “appeals with such power to the soul” but that he can’t quite pin down. Moby Dick represents to Ishmael a kind of infinity that “shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation.” The whale is something that cannot be truly understood by mere mortals, let alone slain by them. The attempt only results in destruction.

Around the same time, a group of American landscape painters who were influenced by the Romantic style came to be known as the Hudson River School. Prolific in the mid-19th century, these painters played with light and shadow to depict detailed, idealized representations of nature and landscape, often bathed in a divine luminescence. The paintings created by Hudson River School artists are full of atmosphere, depicting majestic spires, towering waterfalls, picturesque lakes, and tranquil meadows. Some of the works are truly stunning, and emerged alongside the expansion of the American frontier as settlers colonized westward. The art went hand-in-hand with the idea of Manifest Destiny: the belief that white Americans were preordained by God to spread across all of North America. The conviction was often invoked to justify the removal or slaughter of Indigenous peoples to pave the way for democracy and capitalism.

The 2018 hit video game, Red Dead Redemption 2 pulled heavily from the Hudson River artists for inspiration for the game’s visuals — and to be fair, it looks stunning. But then, what doesn’t these days? The resolution and realism of the imagery we flood our eyeballs with gets better every year. I was even able to generate incredible images to pair with this article with the benefit of AI. It’s never been more simple to capture and transmit what should be a sublime experience — and yet, it feels like it’s that much further out of reach. I emailed Dr. Alex Wetmore, assistant professor of English at UFV, for help in looking at this problem.

“So where does this leave the sublime now?” asks Dr. Wetmore, rhetorically. “Some thinkers have argued that, given how the domain of pure, unspoiled nature is shrinking and more and more of human experience is mediated by technology, the natural sublime is being displaced by experiences of the “technological sublime,” where people increasingly take refuge (spiritual, psychological) in digital, artificial environments.”

Wetmore reflected on a recent experience playing Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom with his children, at a moment when the protagonist leaps from a floating island to a lake far below. “We all exclaimed ‘whoa!’ when it happened, and I felt a similar nervous thrill to when I’ve been hiking up in the mountains in B.C.” I too have had similar moments of awe in video games, from the time I first set foot on a Halo ring in 2001, to a thunderstorm on the plains in Red Dead 2. What’s funny is that the better graphics didn’t produce a more emotional experience — it simply diminished previous ones by comparison.

“The pleasure seems very much akin to the sources of sublime feelings the Romantics represent so memorably as inspired by nature,” writes Wetmore. “Yet the environment is also entirely virtual and artificially created.” He asks, “Is this a degraded or lesser experience because the “nature” depicted in this game isn’t purely or authentically “natural”?”

I think at the core of the truly transcendent emotional reaction that philosophers like Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant describe as Sublime suffers from generation loss: the problem of diminishing quality when you make subsequent copies of copies. What happens when you describe the indescribable, and then ask someone to reproduce it? The feeling at the heart of the existential moment when you’re filled with an awesome terror and reverence should evoke a feeling of oneness with the universe while humbled in the presence of it. It’s the juxtaposition of profound connection to the planet, and disconnection from our own ego. Can we say this is so for the Western conception of the sublime?

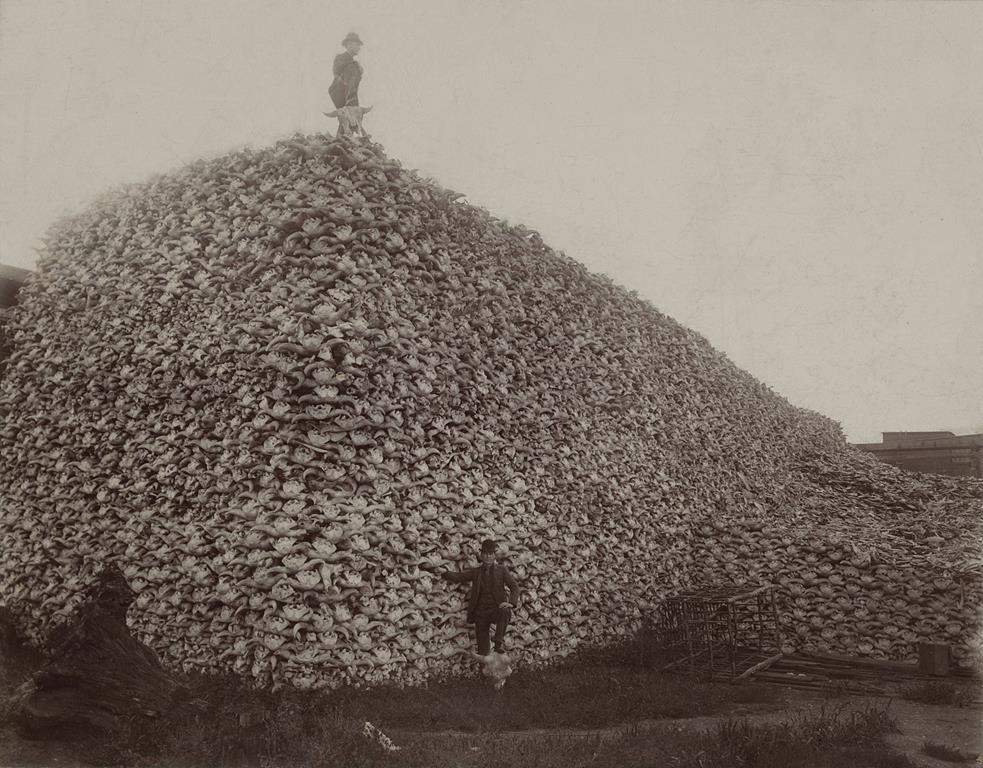

Hand-in-hand with the settlement of the West and its mythological depictions by the Hudson River School painters was the absolute eradication of the American Bison. With an estimated population of well over 30 million bison in 1800, thanks to widespread settlement, tourism, and the desire to starve Indigenous people of an important resource, Bison were hunted without mercy beginning around 1840. According to the U.S. National Park Service, “By 1894, Yellowstone National Park hosted the only known wild herd in the United States.” Roughly 300 Bison remained.

So too with Moby Dick and the whaling Industry. Even though petroleum became more widely available beginning in the 1860s, it was not the stay-of-execution for the whales that commentators believed it to be. In 1861 Vanity Fair ran a cartoon depicting whales throwing a “Grand Ball” in celebration of oil wells discovered in Pennsylvania. It was too optimistic. What the prevalence of cheap, abundant petroleum really did, was fuel a frenzy of technological developments that would wreak havoc on the whales (and many other species besides). Sail ships, rowboats, and spears gave way to massive steam-powered vessels and exploding harpoons that allowed whalers to hunt larger species more efficiently, and in new territories. Blue whales — the largest known animal to ever exist on the planet — were suddenly in play.

The 20th century turned out to be the worst time in human history to be a whale. Estimates now put the number killed at roughly three million. Despite requiring fewer whales for industry and illumination, they still made their way into luxury goods like corsets and perfumes. Factory ships were developed so they could be processed at sea, increasing the number of whales that could be hunted. A perfect example of the tragedy of the commons, the international competition for a shared resource in decline only energized the industry. In the years following WWII, Soviet fleets killed approximately 550,000 whales (while only reporting 360,000), despite warnings from their own scientists dating back to the 1930s. As with animal pelts and ivory, the more rare these goods become, the more profit and prestige they command. As species decline, the pace to extinction quickens. Without serious intervention (sometimes on an international scale), the planet’s rarest and most spectacular creatures are living on borrowed time.

Is it an overreach to claim that the commodification of Sublime experiences causes these global horrors? Probably. But it may exacerbate them. If romanticizing the environment led to a renewed devotion to its stewardship and protection, we’d have long since addressed our tendency to rampage across the earth. Artificial sublimity, for all its beauty, fails to instill the terror and reverence required to drop-kick us out of our apathy and self-regard.

Perhaps — regardless of their intentions — the Romantics (and those who followed them) only succeeded in vaccinating their audiences against the truly sublime. Maybe by giving their audiences a weakened dose of the genuine experience, they were immunizing the population from the effects of the real thing. Maybe we still are.

“…at a certain point we’re gonna have to build up some machinery, inside our guts, to help us deal with this. Because the technology is just gonna get better and better and better and better. And it’s gonna get easier and easier, and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen, given to us by people who do not love us but want our money. Which is alright. In low doses, right? But if that’s the basic main staple of your diet, you’re gonna die. In a meaningful way, you’re going to die.” — David Foster Wallace.

An Uncertain Future

He reaches out to touch the rough granite obelisk. It’s close to 8 p.m., and yet the grassy knoll on which he stands is bathed in daylight. Twin mountains, rocky and naked, stand in the distance on the other side of a wide inlet. He hears the waves, gently lapping on the shore a short distance from him, but he cannot smell the brine of the ocean. He hears the calling of seabirds, but cannot see them soaring above his head.

His palm strokes the rough surface of a megalithic dolmen: an entry marker to an ancient burial tomb. He cannot enter, but he’d read a description of the site, and feels he knows what to expect. He’s more interested in the rocks anyway, curious how primitive humans would have moved the massive objects — not so interested in the why.

Sensors transmit information to the gloves he’s wearing, causing tiny vibrations to ripple through his palm and fingertips. He makes a slight adjustment to look behind one of the standing stones, but sees that there is a missing patch in the rendering. It frustrates him. Stonehenge was better, he thinks, before remembering that this location was included as a free bonus. Still, he considers it a second-rate product, and asks his virtual assistant to remind him to leave a review.

He opens a small window in the corner of his field-of-view, and selects an image. Instantly, a vibrant, semi-opaque menu is superimposed on the landscape. Even though it’s projected mere millimeters in front of his eyes, it appears to hover at arms-length just in front of him. He reaches out a hand and scrolls through the menu: Serpent Mound, Ohio; Machu Picchu, Peru; Knossos, Crete. He’s unsure where to explore next.

A notification window pops up from the bottom of the screen with a news bulletin: “Last known Orangutan dies in captivity.” Oh no, he thinks, lingering for a moment on the image in somber reflection before clicking back to the menu. Gesturing with his hand, the options scroll past in a blur until they halt at the top of the menu, with “Angkor Wat, Cambodia” displayed. I think that’s where Orangutans lived, he ponders. They didn’t. They lived in the jungles of Borneo, and Sumatra — and for a time — in the transience of human memory.

Long ago, when DeLoreans roamed the earth, Brad was born. In accordance with the times, he was raised in the wild every afternoon and weekend until dusk, never becoming so feral that he neglected to rewind his VHS rentals. His historical focus has assured him that civilization peaked with The Simpsons in the mid 90s. When not disappointing his parents, Brad spends his time with his dogs, regretting he didn’t learn typing in high school.