By Michael Scoular (Contributor) – Email

Print Edition: October 8, 2014

Clouds of Sils Maria

Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep opens with a lively film production office, the soundtrack filled with prop orders, airplane arrivals, and chatter about a film director whose artistic powers are on the decline. However, his new film about the life of an actor doesn’t have a word of dialogue that isn’t part of a phone conversation (or about to be interrupted by one) until after its first fadeout — Assayas’ way of adding a few breaths between scenes.

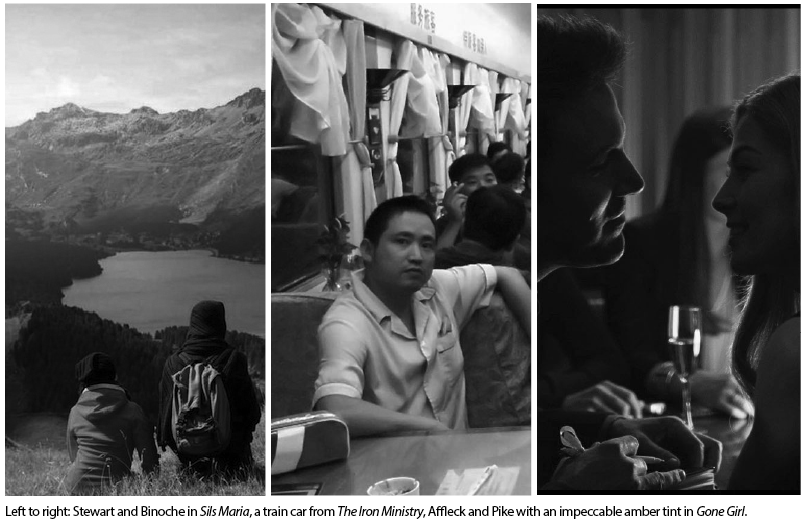

Set totally in the present (more on how that works in a bit), Sils Maria could be described as a drama about an actor, Maria Enders (Juliette Binoche) who is offered to play the older lead in a play (Maloja Snake) where she once played the younger, star-making part. This is a work surprisingly resilient to narrative progression — Enders deliberates, but the majority of the film is spent in attempted isolation, reading the play and arguing about it with her personal assistant (played by Kristen Stewart) on the lower foothills of the Swiss side of the Alps.

Taking place after Maloja Snake’s playwright’s recent passing (Sils Maria would make a great double bill with Alain Renais’ You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet), this death doesn’t hang over the film so much as ease it into an alternate world. The two take refuge from a world of publicity by talking about movies, their generational differences, and the blurring roles of their informal reading of the play. Much of Sils Maria comes across as a combination of the easy conversational work of Whit Stillman (a night where Stewart argues for the legitimacy of YA entertainment) with Assayas’ own background in film criticism (the silent mountain films of Arnold Fanck make a recontextualized appearance). Binoche and Stewart give loose, open performances — the film’s tone and narrative direction seem completely free to go wherever the two might improvise; as Sils Maria eventually draws toward a conclusion, any sense of loss comes not from the details of a narrative, but the end of their performances, which Assayas elevates through a Pachelbel-scored sweep of natural phenomena.

The Iron Ministry

A perspective completely open to the natural world guides the work of the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL), responsible for some of the best documentaries of the last few years (Sweetgrass, Leviathan, Manakamana). The Iron Ministry, directed by J.P. Sniadecki, works like a video corrective to Lixin Fan’s Last Train Home, which, like The Iron Ministry, was recorded on cross-country Chinese trains, all narrow aisles and crowded compartments, but focused on a single family returning home for the holidays. Snidecki’s work was recorded over three years, and is far more wide-ranging. Much of it takes place in conversations: both those that occur between passengers (from politics-debating students to religion-discussing strangers) and take place between Sniadecki and other commuters, where his role (Sniadecki’s American) and his camera (notably the space it takes up) are acknowledged.

The SEL’s commitment is to document people with minimum interference (scenes are not staged, title cards don’t summarize) while also not ignoring the difference a recording device makes. This approach results in several moments of gradually uncovered honesty but also performative flair: one child gives the best comedic monologue of any movie, fiction or non-fiction, this year; and as Sniadecki’s exploration of roomier, upper-class quarters gets blocked off by government officials commanding “no filming,” the work acquires some of the urgency that drove the train/class-division action film Snowpiercer, released earlier this year.

But The Iron Ministry isn’t after nearly the same kind of goal as Bong Joon-ho’s movie: at multiple points the image breaks off into abstracted motion that uses the shake of traincars and pinprick lighting of tunnels and interior artificial lamps to similar ends as the experimental passages that divide Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life or open his To the Wonder. (It’s likely that Sniadecki’s work has a more appropriate comparison, but the beauty both are after is not separated by much.) Whether these shots or the Tibetan fable recounted by one woman that gives the work its title, Sniadecki’s documentary imparts both realistic detail and a sense of grand imagination within several rural and factory workers of an otherwise over-generalized Chinese people.

Gone Girl

David Fincher’s Gone Girl wasn’t playing as part of VIFF, but I saw it in between screenings at the festival (simultaneous to its opening the New York Film Festival), which had the effect of including it as part of the larger dialogue that emerges between movies seen back-to-back-to-back. Gone Girl can and will be compared to seemingly any bit of relevant culture on marriage and manipulation. However, its largest debt comes from within the film world. Like the “comedies” of Stanley Kubrick, Fincher’s humour is in tune with societal ills, distorting human problems until they offer only one way out — in this case, marriage as plot. As with his contemporary Steven Soderbergh, Gone Girl is a digital montage that picks up on political signals (domestic abuse, tragic publicity, patriarchal order) only to divest itself of any easily identifiable ideology, dipping into de Palma-like excess along the way (though, like in Soderbergh’s Side Effects, de Palma’s lurid excess becomes a cold knife in the ribs in Fincher’s hands).

Fincher, keeping the same major creative team from The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, has not evolved beyond the slick cutting rhythms and multiple timelines of that first title. Tied to the script by popular novelist Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl casts a web of references and critical observations over a slight story that is more notable for the performances it allows (Ben Affleck, smile and chin critiqued, voice and speeches perfectly mocked; Rosamund Pike, taking on roles in flashback and parallel, voiceover spilling out comedy as much as Affleck’s does his barely disguised loathing) than the large gaps it distracts from. Amidst the information overload of careers, financial setbacks, and fucking, the novelist witticisms of jokes about Proust, quinoa, and book release parties, Gone Girl’s aims are limited to calling out fakers. Fincher is a director famously interested in “leaving scars,” but Gone Girl is a work of flattered intelligence (the twists! the scathing remarks about marriage!) to the detriment of any lasting effect it aims for. Like Fincher’s Panic Room, Gone Girl is immediately effective at charting suburban architecture, and, aside from some spare actorly insights (Affleck’s compulsive narcissism, Pike’s misanthropic need for silence), lousy when it comes to filling it with anything that can’t easily be piled in with the trash.