Print Edition: October 10, 2012

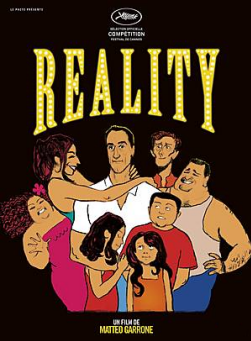

Reality (Italy)

Matteo Garrone’s Reality might at first seem to be a relentless satire of reality television and its hypnotic vacuity. Local Napoli seafood shopowner Luciano (Aniello Arena) reluctantly assents to audition for Big Brother to satiate the cries of his time-invested, celebrity-adoring children. He goes, he introduces himself to an audience that may or may not exist, and then he waits for results after the interview begins.

In the moments after any interview, instant replay and analysis take over the mind, even the most casual sentence becomes something to be taken seriously, but Luciano and Garrone, take this more than a few steps further than even that. For Luciano, the distinction between the possibility of a larger audience and the reality of the one surrounding him disappears, and the question of if he should change the way he acts to stand out, to be exceptional and noticeable by a higher power, seizes him completely. This conviction bears a spiritual echo, and rather than make some sort of comment that reality television is the new religion, hardly worth dredging over a feature length, Garrone takes this highly visible medium and makes it the unexpected seed for lifechanging belief – initially self-serving, but gradually growing into something that makes the surface beginning of Reality look unrecognizable from its spiritual end. Its dreams of show business acceptance, reminiscent of Visconti’s Bellissima in its shattering volume and impassioned argument, fade away, moving to a direct invocation of Tolstoy’s “Where Love Is, God Is,” and Plato’s Cave, only with its shadows encased in holy light and its subject unchained and gleeful.

But that isn’t to say Garrone is all references here. They are used to make the topic unmissable, as is the ubiquitous religious iconography—neon-illuminated, wall-hung, carried, packed into the frame—but what shapes this perspective changing is Garrone’s distinctive camera movements. As in the journalistic Gomorrah, Garrone shoots with roving camera in long, long takes, preserving continuity of time and place. Rarely stationary, rather than cutting to, the camera glides, turns from a close-up of a face, to behind in an over-the-shoulder perspective. Viewpoint splits between what Luciano wants to see inside himself, changing, searching for what this all could possibly lead to, and outside, as family members question his new motivation (“It’s all in your head”), and “the one who says he is from Big Brother” is revealed to not have the answers he seeks. It’s a brilliant relation of the conflicted Ivan Karamazov’s conversation with himself, or possibly another: “As long as I do not know the secret … two truths exist for me: one truth is theirs over there, of which I know nothing, and the other truth is my own. And I am still not sure which of the two is worse.”

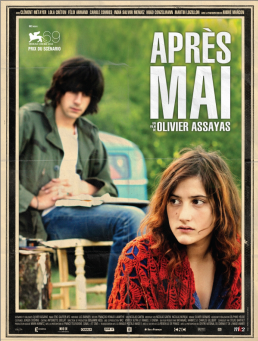

Après mai (France)

It’s either hopelessly limited or exactly appropriate for an undergraduate to try and write about Olivier Assayas’s Après mai. If not for the young thinkers who want to protest inequality and injustice today, then who is this film for, but at the same time, Assayas is addressing a specific group he knew growing up in 1970s France, with his own specific set of memories, critical thoughts, ephemeral love for the people he knew. Someone just starting out in that position, in a wholly different climate, with no way of knowing how to truly understand this experience (and the unique address of Après mai) can’t be completely trusted to have a critical perspective on it. But maybe, what makes Après mai so difficult to talk about is that Assayas tries to bridge this unthinkable divide, impressing a few condensed hours of foolish mistakes and beautiful mistakes of the young people he was and knew to another, tracing the path from aimlessly wanting to be something, to something with direction.

Lest the recreations of young free love, substance-fuelled bonfire parties, protests in the streets and vandalism after dark get construed as merely reverie, glory, and episodic genuflected period detail, the opening of Après mai has a professor speaking preceding a reading that probably won’t completely hold the attention of his students anyway. It’s an effort to balance the accepted ideals and summations of the era, setting up a reinvigoration of the past as people, from a different time, to be judged or at least reconsidered. Après mai’s (non) judgmental depiction of out of school freedom counterbalances restoring life to the past with viewing it through a critical lens. The campfire guitar listening, student group assembling, alternative weekly distributing that follows could be dismissed as trivial, but the observing, struggling to grow as thinking, expressing individuals are always within eyeline in the corners of Assayas’s frames, doing over correspondence and shared internal conflict.

What strikes about Assayas’s film, even more than the soundtrack or the attraction of flinging Molotov cocktails and love in the grass, is the way its main character Gilles (Clément Metayer) and the smaller group of friends of his that take up most of the movie’s focus talk and think about themselves. Assayas frames their story in a way that judges by what it keeps and excludes from the time, but also does not judge in an enclosing way what’s included. They are in their own minds, sizing up society and incorporating all the influential speakers they find agreeance with, but as this is happening there is the beginning (nearly everything done in Après mai is for the first time) of searching beyond these ideals of self-greatness, being the one to understand everything. Ideas about movements, philosophers, political film groups and institutions are challenged. The police state is attacked in thoughts, but the only one harmed when action is taken is a school security guard. Rejection is valued, but the realization that there must also be communication, a consideration of others begins to take hold. What opens with a scratched out anarchy symbol in a desk becomes a scratched out consideration of the people known to Assayas, and his audience. The title indicates an “after” and the movie depicts the generation immediately following the events of May 1968, but this after is unending, and Assayas, by personal tracing, after-images of clarity, resurrects and resends a perspective, to be denied or accepted neither, but to exist consciously in the gap between learning by observing and knowing by experience.

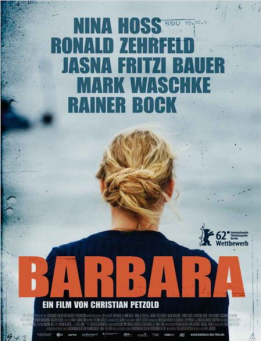

Barbara (Germany)

Limited in location, emotion, and narration, Barbara is too confined, too neat, too easily observed for what it is, it seems. It’s straightforward almost to a fault, and every line seems to hold meaning related to some person characteristic or feature of the plot. But these mechanisms of lines, visually and speaking that give away everything are exactly too-everything. Christian Petzold’s film sets up these boundaries not to go outside of them, to break their hold flamboyently, but to go inside of them, immobile for the most part, but holding what will matter, if anything in this movie can be said to matter more than every other detail and its invisible counterpart, underneath.

Barbara (Nina Hoss), relocated to a small East German town so separate it exists like an island in the film, has been tasked with carrying out the practice of town physician. All along a central colleague-observer (André, portrayed by Ronald Zehrfeld) and the entire environment amd its population hold her in sidelong glance. Uncommunicative, but profiled precisely by her new neighbours as she reorients her routine but seeks to break it, Barbara works at deflection, at the removal of all flourish to fit in. Petzold’s frames are extensive, but only in that they cover the minor extent of the medium-sized hospital and sub-standard quarters Barbara finds herself in, motionless save for when Barbara commutes via bicycle. This one act open to deviation as visible by everyone provides most of the film’s counter to the control of ruling bodies. The land, which could never be seen this way based on the in-town streets and indoors setting of the rest of the action, is windswept and expansive, and densely treed in an Ivan’s Childhood-like dalliance.

This austere, easily interpreted exterior giving way shows itself in the most overt reference in Barbara, as Barbara in one scene chooses from the limited library the one English-language book: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Aloud the account of faking a death and escaping is read, and it’s easy to see where this could be applied to prediction of movement, perception of tendency. But this is a diversion as skillful as the storytelling of her intelligent, ingratiating overseer. Huck Finn is a most frequent unspooler of tales to disguise true paths and inclinations, and Barbara, translating, finds a hidden appeal of messiness in her non-reveal. At all points, Barbara is requested—ordered—to work within a system for the benefit of everyone else and her own slow detriment. What Petzold has crafted is the insertion, forgettable, missable, small, of barely noticeable freedom into this stifling command.

Ernest et Célestine (France, Belgium)

While it’s likely a result of seeing this in a film festival less than 24 hours after Olivier Assayas’s latest, the commonalities between Ernest et Célestine and Après mai are less superficial, more indicative of a shared inclination towards creation over stultification.

Hand-animated Ernest, a post-hibernation bear, and Célestine, a mouse whose job requires venturing into supposedly predatorial territory, occupy the centre of the film. Similarities come in the desired demolition of dictating forces, the urge for change to inequal rights among classes of people, and undivided love and attention to art, all mixing and coming up for animated air.

Imprinting ideas on children is something not ignored in Ernest et Célestine, as it opens with a familiar ancient, though not dead, idea of telling stories to instill fear and obedience in impressionable minds. The ideas listed above are notable criticisms, ones that usually indicate a position of cynicism or liberalism, but what directors Benjamin Renner, Vincent Patar and Stéphane Aubier do is bring this to its unaligned essence, creating a movie that doesn’t condescend, forcing an ideology on children, but instilling cause for hope: it is for creation and love, against not caring and separation. That the oppressive forces in the film are in the form of a police state and an inattentive-to-minorities ruling court of law that segregates people based on their background is what makes the Après mai resemblance so noticeable, but Ernest et Célestine does have branches in abundance as well.

While no less concerned with what goes on in the mind and the heart, Ernest et Célestine is a film of velocity and wall breaking comedy, flying through locales with unrestrained optimistic fierceness. A beautiful break from the monotony of computer graphics, Ernest et Célestine is also divergent from the majority of the classically animated Disney tradition. Backgrounds are as watercolor paintings, splashes of color against white space, scored by playful jazz. This is animation as spur to imagination, not merely the “imagination” of anthromorphization, whether it’s mapping out a world in quick strokes, a King Kong-esque action scene, or beautifully, rebelliously, doing away with assaultive differences.