Date Posted: October 13, 2011

Print Edition: October 12, 2011

In coming to Vancouver from Abbotsford, the Vancouver International Film Festival (VIFF) was not only a wider selection of movies, but an opportunity to see them with other movie lovers. The infectious laughter at I Wish and the rush of applause at the end of Bullhead were unbelievable compared to my previous theatre experiences, and while the quality of the movies and their projection is worth noting, it was those moments that made the largest impression on me as a first time attendant of VIFF. Seeing some of the same people at the various screenings and the way a conversation can be started with anyone waiting in line or for a movie to start (because everyone at VIFF shares that common interest) are what is missing on a trip to the multiplex. The movie itself is the centerpiece, utterly unchangeable, but the interactions with other movie critics and devotees that can be made at a film festival are at times more worthy motivations for attending the festival.

The following is what I saw in the first six days of VIFF; check back next week for the second, and final week of coverage.

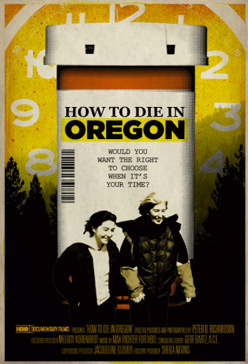

How to Die in Oregon (USA)

How to Die in Oregon is a documentary centered on the issue of assisted suicide, or as the people in the film prefer it to be called, “dying with dignity.” Attempting to raise awareness of the topic without overtly taking a side through voiceover narration or a barrage of one-sided statistics, the movie relies on brief context. It provides title cards and a heavy emphasis on interviews with patients considering the route of planned death via ingestion. How to Die in Oregon covers a surprisingly high number of cases, yet each portrait ably details their current situations in life through unbroken dialogues. In all the homes the camera enters—whether that of an elderly man who’s content with the life he’s lived or a middle-aged mother with months to live—the subjects’ intelligence, humour and self-awareness are intimately portrayed. The process of dying is heart-rending, conflicted for some, and shown quite simply as unvarnished as it is.

How to Die in Oregon is a documentary centered on the issue of assisted suicide, or as the people in the film prefer it to be called, “dying with dignity.” Attempting to raise awareness of the topic without overtly taking a side through voiceover narration or a barrage of one-sided statistics, the movie relies on brief context. It provides title cards and a heavy emphasis on interviews with patients considering the route of planned death via ingestion. How to Die in Oregon covers a surprisingly high number of cases, yet each portrait ably details their current situations in life through unbroken dialogues. In all the homes the camera enters—whether that of an elderly man who’s content with the life he’s lived or a middle-aged mother with months to live—the subjects’ intelligence, humour and self-awareness are intimately portrayed. The process of dying is heart-rending, conflicted for some, and shown quite simply as unvarnished as it is.

But while the people and the cause they support are moving and convincing, the problem of How to Die in Oregon is, despite its director Peter Richardson’s claim that the movie is not intended to take sides, apparent in its leaning. The singular interview subject not on board with choosing his own death date is shuffled off after three minutes. Anyone opposed to the option is considered a religious nut. Taking on a highly relevant and contentious issue, How to Die in Oregon hopes to be a zeitgeist-seizing important movie that will be shown to unconvinced friends and family. But in its slant, How to Die in Oregon falls far short: it refuses to be as open-minded as it asks its audience to be, and accomplishes little beyond being a collection of moving tributes.

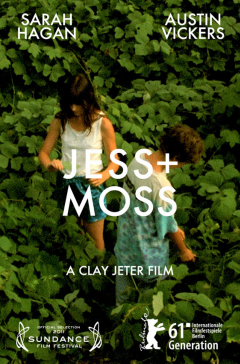

Jess + Moss (USA)

Jess + Moss is a kaleidoscopic, nostalgic showcase for director Clay Jeter’s considerable talent. Consisting of moments locked in Moss’s memories (and Jeter’s, using settings from his own childhood): the hopscotch narrative, of a summer spent doing nothing except spending time together, is realized through saturated colours and film stocks with varying levels of graininess and exposure. The experimentation with time and aesthetics is intriguing, fed through the conceit of a tape recorder Moss uses to hold on to all of the fleeting minutes of the formless season, but the execution on the part of the young actors is less successful. With a heavy emphasis on tape playback sounds and soundtrack, the two children factor little into the movie dialogue-wise. Unfortunately the little that is theirs is fumbled, giving off the efforts of strained casualness, rather than unforced realism. The shots are beautifully framed, but the young actors are not as skillfully blocked.

Jess + Moss is a kaleidoscopic, nostalgic showcase for director Clay Jeter’s considerable talent. Consisting of moments locked in Moss’s memories (and Jeter’s, using settings from his own childhood): the hopscotch narrative, of a summer spent doing nothing except spending time together, is realized through saturated colours and film stocks with varying levels of graininess and exposure. The experimentation with time and aesthetics is intriguing, fed through the conceit of a tape recorder Moss uses to hold on to all of the fleeting minutes of the formless season, but the execution on the part of the young actors is less successful. With a heavy emphasis on tape playback sounds and soundtrack, the two children factor little into the movie dialogue-wise. Unfortunately the little that is theirs is fumbled, giving off the efforts of strained casualness, rather than unforced realism. The shots are beautifully framed, but the young actors are not as skillfully blocked.

Still, Jess + Moss’s less accomplished elements do not hide the fact that Clay Jeter has the tools to make something great. His still-frame compositions of Jess and Moss’s dilapidated living arrangements recall Jim Jarmusch’s Permanent Vacation, another movie in a convincingly-detailed time and place, but not possessing a great performance or a fantastic script. However, as with that debut, there is real potential here; that, in the end, is what makes Jeter the most exhilarating part of this movie.

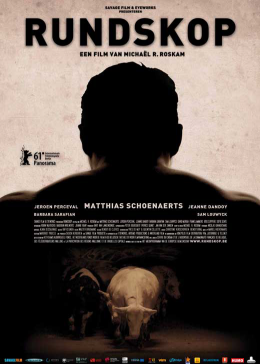

Bullhead (Belgium)

Bullhead is another debut film, but one occupying a completely different level of accomplishment. Focusing on a tortured man working in the business of dealing cattle steroids, Michael R. Roskam is able to pen a script that never veers from what seems credible in the movie’s universe. It does this by alternating scenes, expansive and shrinking, that work with lead actor Matthias Schoenaerts and cinematographer Nicolas Karakatsanis to create a palpable character in a stunning, lived-in world. While its primary focus is singular, the quality of Bullhead’s secondary characters ground the movie, serving as a contrast or a lift from the brooding, massive presence of Schoenaerts’ performance. Their humour and mixture of heightened realism and low-key monotony accomplish what couldn’t be filled in if Bullhead was solely a character study.

Bullhead is another debut film, but one occupying a completely different level of accomplishment. Focusing on a tortured man working in the business of dealing cattle steroids, Michael R. Roskam is able to pen a script that never veers from what seems credible in the movie’s universe. It does this by alternating scenes, expansive and shrinking, that work with lead actor Matthias Schoenaerts and cinematographer Nicolas Karakatsanis to create a palpable character in a stunning, lived-in world. While its primary focus is singular, the quality of Bullhead’s secondary characters ground the movie, serving as a contrast or a lift from the brooding, massive presence of Schoenaerts’ performance. Their humour and mixture of heightened realism and low-key monotony accomplish what couldn’t be filled in if Bullhead was solely a character study.

As for where the movie’s attention mainly lies, while much of Schoenaerts’ portrayal of the character of Jacky is memorable for what comes from the repeated animalistic parallels, which come close to becoming overbearing symbolism, the way he carries the movie (in his face and in his movements) erases disbelief. No matter what he is called over the course of the movie, Schoenaerts makes it seem natural. The allusions might as well not exist, for all the effect it has on him. And that is what makes the twists of the plot, the sometimes crude subject matter, and the grandiose qualities of the movie all not merely passable but something that adds up to a satisfying first feature from Roskam.

I Wish (Japan)

Hirokazu Kore-eda has become known for tackling familial stories with an Ozu-like style, both visually and in his avoidance of sentimentality. The difference that comes with the generational divide, often irreconcilable between parents and children, is a familiar theme, but in I Wish, Kore-eda takes a more lighthearted approach to the subject matter.

Hirokazu Kore-eda has become known for tackling familial stories with an Ozu-like style, both visually and in his avoidance of sentimentality. The difference that comes with the generational divide, often irreconcilable between parents and children, is a familiar theme, but in I Wish, Kore-eda takes a more lighthearted approach to the subject matter.

The exuberance of the child actors playing the schoolchildren, that are at the heart of this film, is a welcome change from the far-too-intelligent, mechanical acting style that is prevalent in many current child actors in Hollywood. Yet this air of playfulness does not completely omit the uncompassionate nature of life that Ozu was able to draw from and portray on the screen that Kore-eda follows. It is not the forefront of the picture, which mostly stays on the high adventure of the children, but moments where a group of drunken grandfathers wonder, “Does this young generation feel strongly about anything?” or the children’s enthusiasm turns into small realizations work in tandem with the relentless laughs that arise from the playful line delivery and physical comedy to make for a movie that, while not as poignant as the best of this director or his influences, is still more than enjoyable fluff. I Wish could have stood to lose 10 mostly unnecessary minutes from the end of its running time, but Kore-eda’s timeless, universal sense of humour makes I Wish one of the most effortlessly entertaining movies of VIFF this year.

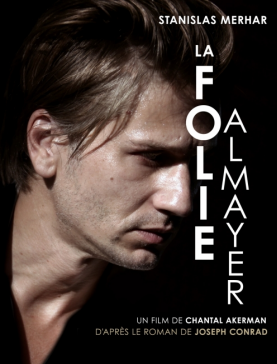

Almayer’s Folly (Belgium, France)

Chantal Akerman, a groundbreaking filmmaker in her earlier works, has a unique style, along with common themes and elements of characterization in her works. Almayer’s Folly continues her exploration of the effects of uprooting on culture and behavior, along with her stylistic strokes of sharply drawn characters who are observed, rather than listened to, over long takes.

Chantal Akerman, a groundbreaking filmmaker in her earlier works, has a unique style, along with common themes and elements of characterization in her works. Almayer’s Folly continues her exploration of the effects of uprooting on culture and behavior, along with her stylistic strokes of sharply drawn characters who are observed, rather than listened to, over long takes.

Almayer and his daughter Nina both undergo a deepening sickness as they are forced to endure the hot foreign waters and forest of Malaysia – though Akerman shot in Cambodia (she also changed the time period from Joseph Conrad’s novel) and are forced to go through a white education against their wills, respectively. While the simplicity of story and dialogue seem to betray whatever narrative depth could be gleaned from so rich a source, Akerman seeks to draw out the indescribable feeling of being stuck in limbo, belonging to nowhere. The essence of character is conveyed, for despite the lack of context, (coming to it unfamiliar with the novel or the politics of the region) by the final, unforgettable shot; every line and feature of the faces inhabiting Akerman’s frame is familiarized – it becomes known to us. Pulling out specific scenes would suggest this is a slow moving film, and yet the experience rushes by, despite a running time of over two hours. What is taken away are shots like Nina, against a blue backdrop of twilight sky and murky water, smoking a cigarette. She doesn’t need to say much, because the camera says it all. A maddening, beautiful movie.

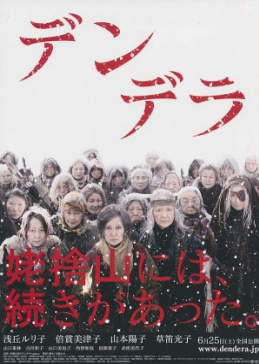

Dendera (Japan)

There are derivative works, and then there is Dendera, in which son Daisuke Tengen attempts to continue father Shohei Imamura’s The Ballad of Narayama. While the latter had its twisted, grossly humourous parts, they were not meant to exist as just that, pointing to more than just sex and laughs in its story of how, in a small village, tradition dictates that mothers are abandoned for dead at 70 by their sons. Tengen bypasses whatever that story said about human life to use its construct to tell a revenge story that would be laughable if it wasn’t so sincere.

There are derivative works, and then there is Dendera, in which son Daisuke Tengen attempts to continue father Shohei Imamura’s The Ballad of Narayama. While the latter had its twisted, grossly humourous parts, they were not meant to exist as just that, pointing to more than just sex and laughs in its story of how, in a small village, tradition dictates that mothers are abandoned for dead at 70 by their sons. Tengen bypasses whatever that story said about human life to use its construct to tell a revenge story that would be laughable if it wasn’t so sincere.

With grade-school ethics and the supposed laughs that can be had from old women practicing with spears, replete with shrieking battle cries, Tengen weaves a dull revenge tale, supposing that the women abandoned for dead actually formed a cult-like band of survivors, hungry for killing. Turning an established tale around isn’t sacrilege on its own, but turning it into a movie filled with scenes, both dramatic and action, drenched in camp and silly violence smacks of desperation and unoriginality. This is not Tengen’s first movie, so the amateur shot selection (expect a lot of old ladies rushing at a shaky camera) is inexcusable and makes it clear why his name isn’t terribly well known at this point in his career, despite his familial connection. The opening shots the two movies say enough on their own; in both, an aerial shot of the mountain village covered in snow is used. In The Ballad of Narayama, unsteady helicopter footage and a greyness of colour show the village as realistic, a part of the mountain. Dendera opens with a postcard-ready steady flyover of a village looking more like a set than anything believable—whether for the purpose of entertainment or something more—Dendera fails on both counts.