By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: October 16, 2013

Enough Said (dir. Nicole Holofcener)

Every movie, beyond its worth as a coherent story or series of images, is a record of people and places at a specific moment in time. Being sucked into a narrative often takes precedence, which makes it possible to appreciate a classic film from the 1930s without constantly thinking of how everyone involved with its making has passed away, or how much of the landscapes or city streets in the background of a shot might still resemble their past record today. But these thoughts do show up, in website projects, in written remembrances, or in the merging of coincidence, such as an anniversary, with a movie screening.

In the case of Enough Said, the passing away of James Gandolfini since the movie finished its principle photography but before its wide release makes his performance more bittersweet, grow larger in significance. But as Ignatiy Vishnevetsky remarked at the time, what marks Gandolfini as a great character actor is how a case can be made for just about any of his performances as his best. Enough Said joins this group.

Galdolfini and Julia-Louis Dreyfuss are both divorced parents with daughters about to head to university, and when they both recognize this, and awkwardly say some variation on “me too!” at the party where they’re introduced, it’s also an introduction to Nicole Holofcener’s style of romantic comedy writing. Rather than perfect repartee and theatrical quotables, Holofcener’s characters are not funny in the way people trying to be funny often end up being, and the movie and its supporting characters embrace them for this.

Holofcener’s style can seem like a close cousin to television (the warmth of many of the relationships and the way characters struggle against the narrowness of their experience recalls a bit of Gilmore Girls), and yes, there is B-plot juggling, and yes, there isn’t much distinguished, musically or visually, about the movie. But Holofcener distills rather than overplays. Enough Said is a movie that respects the individuality of its characters, despite the fact that a romantic union is the subject, to the point where when the comedic staple of embarassment shows up, it affects both characters involved. Gandolfini and Dreyfuss both play with tired courtesy, familiar imperfection, and modest understanding as the scenes play out.

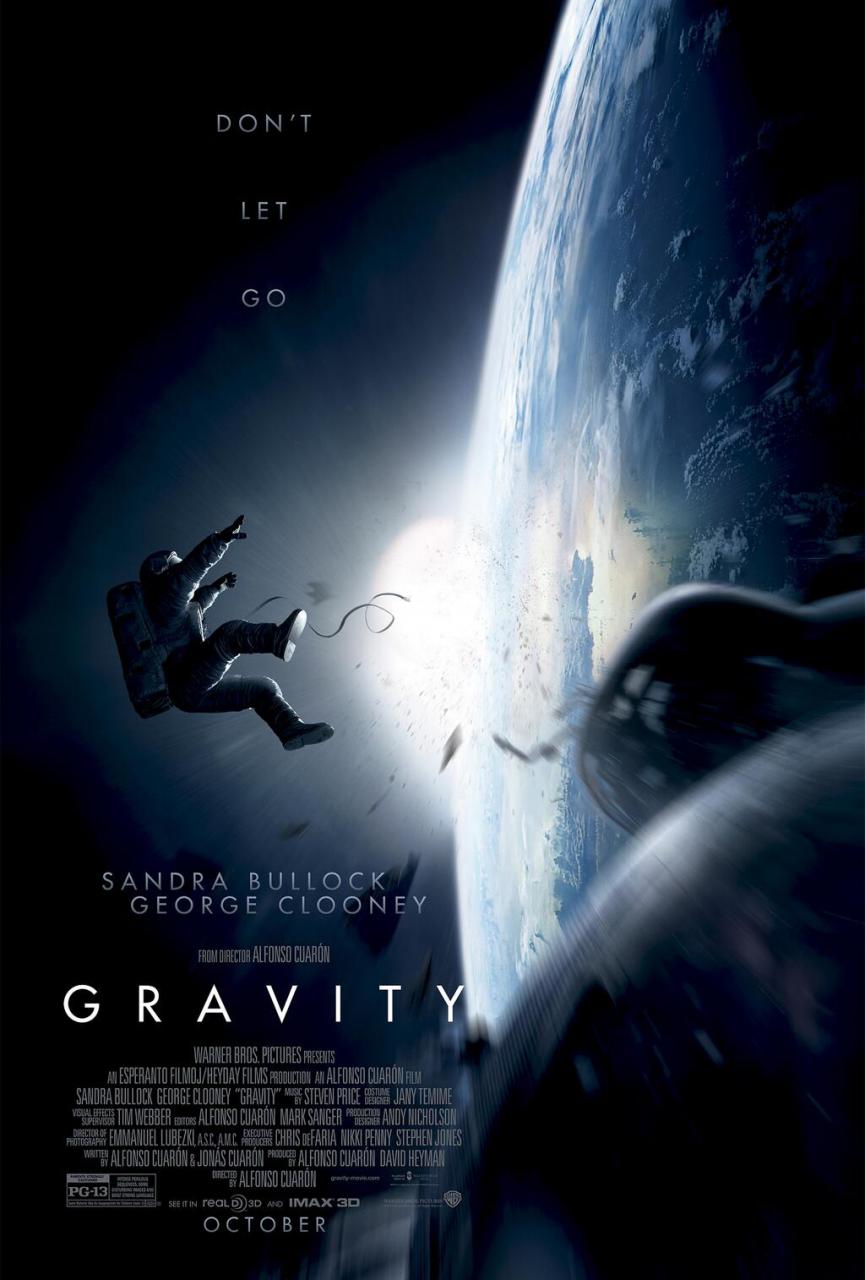

Gravity (dir. Alfonso Cuarón)

There’s nothing modest about Gravity, at least if you hear about it from awards bloggers and advertisement campaigns. The expanse of space usually brings up lofty questions, the key one here being how the idea of being impossibly small makes you feel, with the usual response as either meaningless fear or liberating perspective, but what Gravity suggests is that the whole thing is quite hilarious.

Alfonso Cuarón’s first film in eight years is basically 90 minutes of the seamlessly stiched-together long take (and apparently little else) director playing with excitement, with a little maxim-izing about keeping it together and moving on to make the whole thing relatable (with even this pitched to maximum volume). The ingredients for Cuarón’s space-physics model: the funny, talkative George Clooney, not the serious actor one, a melancholic new-on-the-job Sandra Bullock (reminiscent of her performance in the underrated The Lake House), no celebrating or hands-clutching-head shots of Mission Control, and everything that can go wrong going wrong.

Gravity’s presence as the first semi-realistic space movie in a while has brought out discussions of its attention to reality, and criticisms, because of its explanatory title card about the absence of sound in space, for its use of dramatic score. But despite its (sentimental) message of rationality, Gravity is a movie that cares mostly about dizzy subjectivity: a ridiculous Hans Zimmer-meets-Sigur Rós resurging wave of sound is how the mind, in 2013, chooses to accompany life-or-death situations, and despite the same problems of plane-separation, 3D allows the movie to loom as large as it possibly can, the scientific possibility of its subjects thrown to the wind.

Gravity is a movie where everything humans have launched into space is turned into a mortal weapon, which is less horrifying discovery and more of an opportunity for fun, pitched at such a concentrated level of out-of-breath adrenaline that it, switching between beauty and goofiness, begs to be counted as a reason to be happy to be alive.

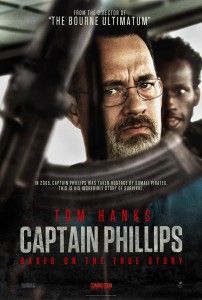

Captain Phillips (dir. Paul Greengrass)

Realism and shaky cam still have the same tired relationship (something wonderfully absent in Gravity) and Paul Greengrass is probably the name most associated with this marriage. At this point, most will be familiar with the logic of the style’s spatial leaps and unsteady hand, but simply accepting the mode Greengrass uses in Captain Phillips robs the movie of any of its contradictions, something carried over from Greengrass’ previous, mostly-forgotten Green Zone.

In that film, the objectivity and reliability of journalistic and military operations in Iraq were undermined, leading to a happy ending where comeuppance was served. Captain Phillips, on the other hand, is a Zero Dark Thirty-like account of Things That Happened, with some hints at the flimsiness of the intel everyone is acting on. Tom Hanks, in the main role, is believably serious, organizing his crew and operating according to protocol. Speaking without a trace of irony, he’s honest, loyal, faultless. The complications then, come from the film’s depiction of the Somali pirates that attempt to board and take hostage of an American vessel.

There is the choice in the first place to tell this story over any others. Americans, evidently, like to make versions of history that make claim to empirical, straight sequences of events even as there is always a vested interest at work. Captain Phillips makes some effort at humanizing the situation that traps the four main Somalians, suggesting that were it not for American interests shipping cargo through and using the resources from the area, this might not ever occur, and they might instead be fishermen.

Even if it’s barely connective, the framing of the state of affairs recalls the unprofitable fisherman from Luschino Visconti’s La Terra Trema, an example illuminating if only because Visconti, an actual titled count, was making a film about those in poverty, trying to enliven a situation totally not understood. American treatment of other countries, particularly those in conflict, almost always has the same air about it, and not half the care of Visconti’s films. While Greengrass and screenwriter Billy Ray may try to add some internal conflict to the straightforward, if often tense water-vessel-standoff plot, what stands out is how whatever the disclaimers may say, Hollywood cares about fidelity to American military history if nothing else, which leads to lengthy credit blocks thanking every member of the original personnel involved and position titles like Department of Defense Entertainment Media Liason. Even if the military has to stand up to some criticism, it gets the job done. And Greengrass’ camera, super-focused and illuminated in the light of high-tech displays, can’t help but show it off.