By Katie Stobbart (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: May 20, 2015

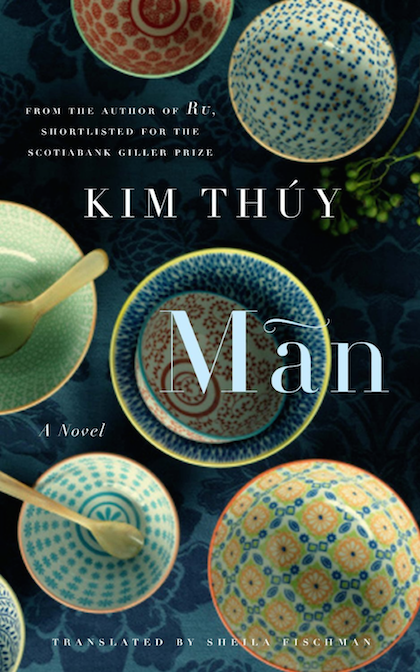

Compared to the intentionally streamlike story flow and strong reflection of central themes in Kim Thúy’s debut novel Ru, the vignettes of her latest book, Mãn, feel scattered across a book whose structure is split clumsily into two parts. A little more than half is marked by extensive and detailed description but little action. The latter part drops this approach, packing in plot with a dash of consequences, ending abruptly with a stunted denouement.

Compared to the intentionally streamlike story flow and strong reflection of central themes in Kim Thúy’s debut novel Ru, the vignettes of her latest book, Mãn, feel scattered across a book whose structure is split clumsily into two parts. A little more than half is marked by extensive and detailed description but little action. The latter part drops this approach, packing in plot with a dash of consequences, ending abruptly with a stunted denouement.

Many of Kim Thúy’s descriptions, especially of food and especially in the beginning of the book, have a sharp, unique focus. However, attempts to link these descriptions to the “food is culture” thesis felt heavy-handed in places:

“It was the last time Maman saw her father: beneath the durians, which the Vietnamese call s?u riêng. Until that day, she had never thought about the name formed by those two words, which means literally ‘personal sorrows.’ One forgets perhaps that those sorrows, like their flesh, are sealed hermetically into compartments under a carapace bristling with thorns.”

Here Thúy’s imagery is strong, but the description as a whole draws the reader out of the story in an almost academic way. The length makes the connection feel forced instead of having an otherwise lovely, simple resonance.

These images also did not recur and thus felt purposeless; instead of remaining in focus they strayed to the periphery, and any image-heavy tangents longer than a paragraph had my eyes drifting from the page, or skimming in search of anchorage.

Sometimes the language, maybe as a side effect of translation, did not feel as strong. I haven’t read Mãn in the original French, but I don’t remember having the same complaint with Ru though both books had the same translator, Sheila Fischman.

I expected the Vietnamese words and phrases in the margins (paired with English translations) throughout the novel to provide that anchorage and speak to the necessity of the vignette format; instead they seemed unnecessary, either because they were obvious or too removed from the vignette, and added little to my understanding or appreciation of the story. The word for “identity,” for example, is paired with a very short section on getting rid of one’s identity for protection. Then the word for “mistakes” is paired with a paragraph on secret education by oil lamplight.

There are a few good examples of character description scattered throughout the novel, like this one of Julie:

“She educated me in languages, in gestures, in emotions. Julie talked as much with her hands as with her wrinkled nose, while I could barely maintain her gaze for the duration of a sentence … She imitated accents with the flexibility of a gymnast and the precision of a musician. She pronounced the five versions of la, là, l?, l?, lã, distinguishing the tones even if she didn’t understand the different definitions: to cry, to be, stranger, to faint, cool.”

However, I didn’t feel a strong, continued connection to or investment in any of the characters — not even Mãn herself, from whom I was separated by a narrative chasm. This was due in part to a quasi-epistolary style in which Thúy tends to recount events in summary, seldom dwelling in a moment long enough to ground and connect with the reader. That is, until Mãn finally meets the married Parisian chef mentioned in the book jacket, on page 79 of 139. This is the moment of that marked shift in focus from description to action before the book speeds toward the end.

Partially because of that awkward division, Mãn is a book I’d have put down if not for the task of reviewing it. That said, it’s only Thúy’s second novel after a winner out of the starting gate, and there’s plenty of promise in her distinct approach and thematic interests. It wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect her to regain ground with a subsequent work.