Dr. Lucy Lee is an invitromatest, a term coined by Lucy and her colleagues to describe the unique work they do growing cells in vitro.

Lucy researches fish cell lines, a cell culture grown in a flask from a single cell that continues to grow seemingly indefinitely. The basic characteristics of these cells can then be analysed, or used in a variety of research applications, from toxicology to pharmacology.

Throughout her 35 years in research, Lucy has grown hundreds of unique cell lines that are now used worldwide. Her first cell line, created in 1983 — the rainbow trout liver cell line — is still used today as a standard for in vitro testing.

Lucy started her career at UFV in 2012 as the Dean of Science. She will be returning to UFV this September after sabbatical/administration leave, which she spent traveling the globe, giving workshops and presentations, and advancing her research program.

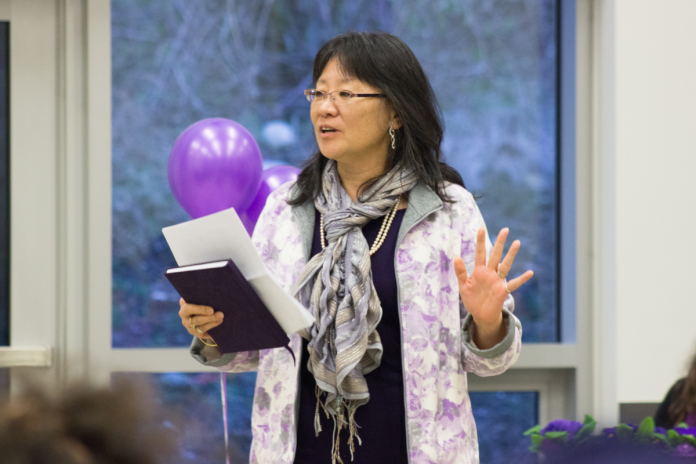

She presented her research Tuesday, Feb. 20 as part of the Faculty of Science Dean’s Seminar Series, where she discussed her past, present, and her thoughts on the future of invitroomics.

What are you most proud of in your research career?

The fact that I’ve created these cell lines. I’ve done easily hundreds of different cell lines of fish.

People do basic research, and then they find the applications later on. When I started, I loved looking at the cells, and I just wanted to see what we could do.

But then, over the years, you see the applications. You see them in toxicology, you see them in medicine, you see them in fish farming, and everywhere.

What made you start in this field?

I lived in Peru, and I went to medical school there. But this is in the 1970s, and the country was in unrest. There were always strikes. In my third year of medicine, there was a countrywide strike. My dad didn’t want me to stay in Peru, because the guerrillas were happening, and people were being robbed.

So, I came to Canada. For medicine here, you had to have a few years in university. I went to Waterloo, the university my brother was going to. I took biology courses, which I figured I could use to apply for medicine. But in my third year there, I took a course in developmental biology, and the labs had hands on cell culture work.

I loved it. I got to culture chicken embryos, and I was a geek. By the end, I’d cultured every part of this chicken embryo, and had heart cells beating in my flask. So that hooked me.

I wanted to do more research with cell culture, and there was really only two people who were doing the research with cell cultures at the time. There was either one with fish, or one with chick embryos. But I didn’t like the professor with the chick embryos, so I went with fish.

I’ve seen you travel a lot with your work. What’s the most interesting country you’ve ever been to?

Well, actually I grew up in Peru, and I still find that’s the most interesting country. I go back almost every year, and there’s always something new, and something interesting. It’s an amazing country.

They have everything. They have all kinds of biodiversity. Not only that, but their Inca culture and pre-Inca culture. There’re ruins everywhere. You go dig in the soil somewhere, and you can find clay pieces.

What are you working on right now?

Right now, I have a new grant for a cell line that is nonexistent in fish: olfactory cells. There are no fish olfactory cells. To get to the cells, I get to chop off fish heads.

How do you make fish cells grow in a flask?

So that’s the thing, many fish have what is called indeterminate growth. They keep growing, and growing, and growing.

It’s unlike humans, who have a limit on how much we grow, unless we have cancer. In humans, there are two sets of genes that control how cells grow, a growth gene, and a “stop” gene. There must be a fine balance between the two genes in order for us to be normal.

In fish, a lot of those that have indeterminate growth seem to have genes that work differently. So, they continue to proliferate, unlike ours, which will stop at a certain time.

It’s an area we should be studying more, especially the expression of those certain genes, because it could give us insight into humans. There’s so many things that are interesting about fish. They’re not just slimy.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.