By Michael Scoular (The Cascade/Photos) – Email

Print Edition: January 21, 2015

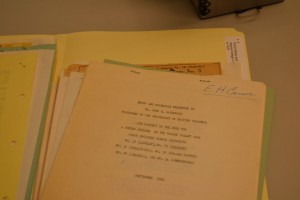

I have come to realize that an archives is not something that you can give a summer student three-and-one-half months to organize and present in an accessible manner. Furthermore, an archival collection of an institution such as Fraser Valley College does not cease to grow when time, money, and space allotted for it has been used up. There is always an urge to reconstruct the past … old records and documents are needed and used by new members, therefore, they must be accessible and stored in a manner so as to preserve them. — Ed Sanders, “Why Establish an Archives” (1977)

Behind two doors covered with blinds in the upstairs stacks of the Abbotsford campus library sits the most readily accessible archives of UFV’s 40 years. It covers less than half of a row of shelving, and exists despite there being no active archives program at UFV, nor a qualified archivist among the university’s staff.

While the lack of a fully organized archive is not a new development at UFV, it has, as an integral part of an academic environment, been explored multiple times in the past, the first in the early years of the institution. Ed Sanders’ proposal came just three years after the formation of Fraser Valley College, when a new dedicated campus building had yet to be built and existing documents or historical accounts would have been few and short. However, its main points remain unaddressed after decades of expansion: that in order to be successful, the archives must be separate from the library, it must be managed by a dedicated archivist, it must be able to collaborate with and receive contributions from the various departments throughout the university, and requires a climate-controlled archival space, not simply storage, as is the case for the university’s holdings in Chilliwack, which are larger in volume than the Abbotsford library’s collection, but unidentified and unorganized.

The most recent concentrated effort to change this occurred 10 years ago when Kelly Harms, an archivist from the Chilliwack Museum, was hired as a consultant to assess the state of UFV’s records, which lay in several locations, some completely unorganized or in poor condition. Harms identified four main archival holding locations throughout the institution, the worst of which, the garage at Friesen House, was infested by rodents and insects, and outlined a plan for the next decade, including policy and a potential budget.

“An archives repository provides a safe and accessible location for records of enduring value, which contributes to overall historical awareness within the institution, as well as the broader community,” he wrote in a rationale contained in his closing report. “This is especially important in light of the retirement of many long serving faculty and staff. The accumulated knowledge, wisdom, and experience of founding faculty needs to be recognized and preserved, in order to better understand the origins and development of the institution.” Harms also recommended an archives applied studies program at UFV.

Following these findings, the damaged materials were assessed and restored, and the current collection in the library was started. But since the 2006-07 academic year, no further work has been funded.

This has left the archives under the management of librarian Mary-Anne MacDougall and logistics manager Bob Peters. “I am not a trained archivist … [archivists] have a very different approach to information management from what librarians do,” MacDougall says. “[Bob] is not a trained records manager. As far as permanent retention with an archival destination, it’s not his job, and it’s not my job, but we do it because we know there’s a need.”

While the archives are in a better location now, the historical record of the people that worked at and attended UFV continues to be added to, and, MacDougall notes, is not being saved. As staff and faculty retire, with no formal policy for archival collection or donation, the most common practice is for documents to be shredded.

“It’s just what people do,” MacDougall says. “They don’t want to take the stuff with them, and there’s no process, there’s no archival program — and Bob can’t manage that, that’s way beyond his scope.”

Similar cases appear in Harms’ report. Photographs lack dates, locations, and other contextual information, and as time passes, fewer people remain who could identify what the photos show. An attempt to compile the history of the athletics program was met with “enormous difficulty” due to a lack of records. And due to a lack of space, 17 of 18 boxes of documentation of the building of the Mission campus were destroyed.

An historical perspective can also change the way decisions are made at different levels of the institution. MacDougall describes how, in order to interest the administation in archival work, they presented documents to then-president Skip Bassford showing previous discussions about the potential purchase of Canada Education Park for UCFV, suggesting that as a university encounters many of the same types of problems and decisions, background on how the university has dealt with similar issues in the past can only help.

“We don’t realize that if there was ready access to this information, we [would] have a better idea of where we’ve been,” MacDougall says, “because the new people that are coming in are not going to have that kind of institutional memory.”

The university continues to be aware of the archive situation. The library advisory committee created an archives and special collections subcommittee in 2011 to discuss the situation again, but due to a feeling that budget reductions and similar priorities would not result in a commitment to any structured plan as outlined in the past, the subcommittee has not met since September 2011.

“Everyone thinks it’s an important thing, but not to the point where financial resources are going to be allocated to it as opposed to something else,” Kim Isaac, one of the university’s librarians, says, adding that provincial funding reduction and the reality that an archives achieves long-term, rather than immediate benefits have only made an archives program less likely.

“I think as an academic institution and an important community agency that’s been in existence now for 40 years, we should have something,” she says. “It could be minimal, but it should be more than we have right now; it should be an identifiable space and we should have done something with those archival materials to make them retrievable and to know what we have.”

University administration was not available for comment by press time.

Elsewhere, in local museums and in the library’s heritage collection, there are community newspapers that document some of the events and changes at the university, but these are mostly limited to funding reports, the announcement of new programs and cutbacks, and an annual article on the student enrollment for the new year. Still, in the absence of an organized archives accessible and directed toward use by students and the community, those are the items that will reach a wider public. Closing his 1977 report, Sanders is particularly blunt, saying, “Without an [institutional] program, there is little use in collecting bits and scraps, cataloguing them, and calling them the Archives.”

There are academic debates over the use of archives more generally, particularly with regard to how much is lost by focusing only on printed documents. Sanders included in his proposal an idea for tape-recorded oral histories, but, like the rest of his report, this would rely on an employed archivist and potential student positions. Today, digital archives have changed the way we think about preservation, but electronic forms require no less expertise and attention from archivists as storage formats change and data expires or is removed online.

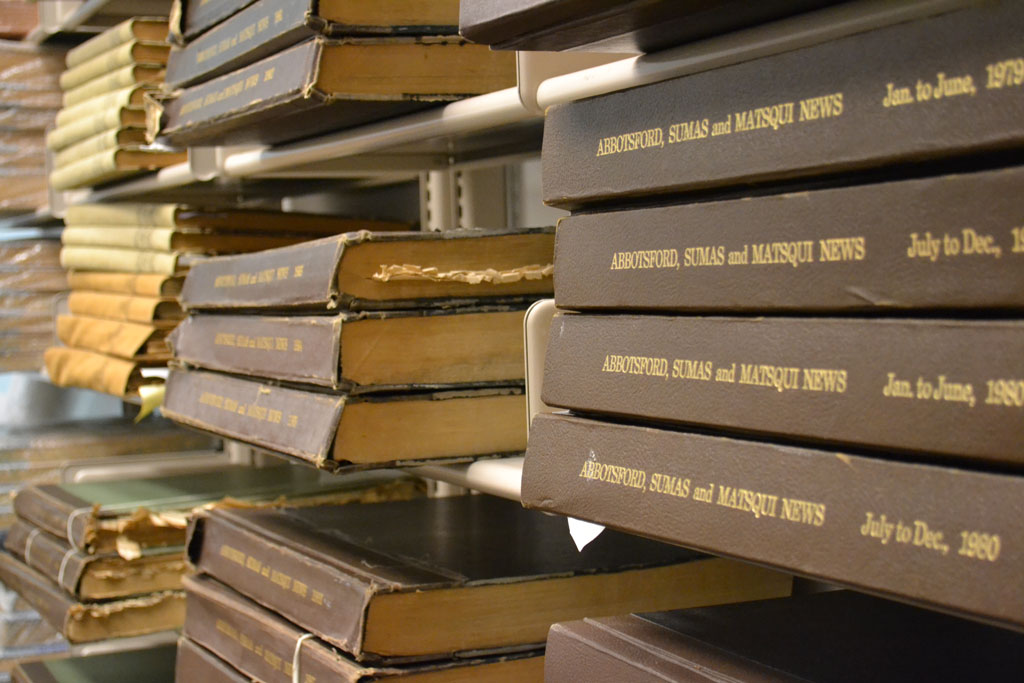

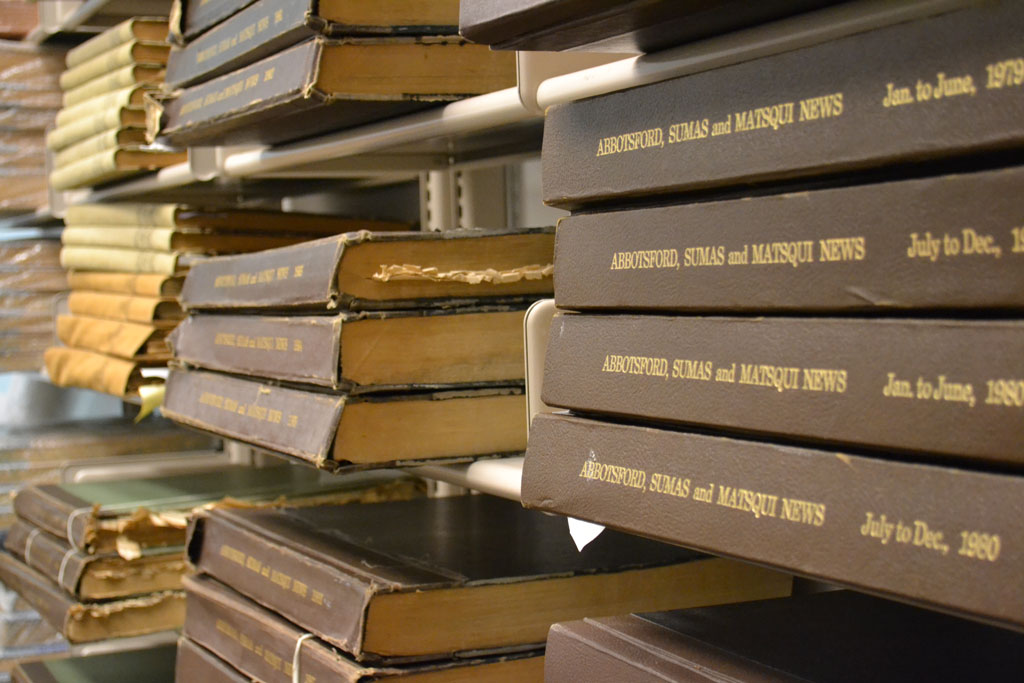

For now, MacDougall has other (funded) projects to focus on, including digitization of century-old community newspapers, map preservation, adding to the library’s heritage collection, and a repository for UFV’s academic output each year. She sees in the scanning and making available of old copies of the Abbotsford-Sumas-Matsqui News, a project done through UBC’s digitization centre, an act similar to what UFV’s archives would potentially provide: “If you look in them, you see the whole life of the community unfolding in its pages.”

One particular advantage that archives have as carriers of collective memory (besides their persistence) is that they can lie unnoticed and undisturbed while individual memories fade, while collective memory is refashioned, or even while there are conscious efforts to efface memory. Archives may be of most value not when collective memory persists, but when they provide the only sources for insight into events and ideas that are long forgotten, rumoured but not evidenced, or represseed and secreted away.

— Margaret Hedstrom, “Archives and Collective Memory” (2010)