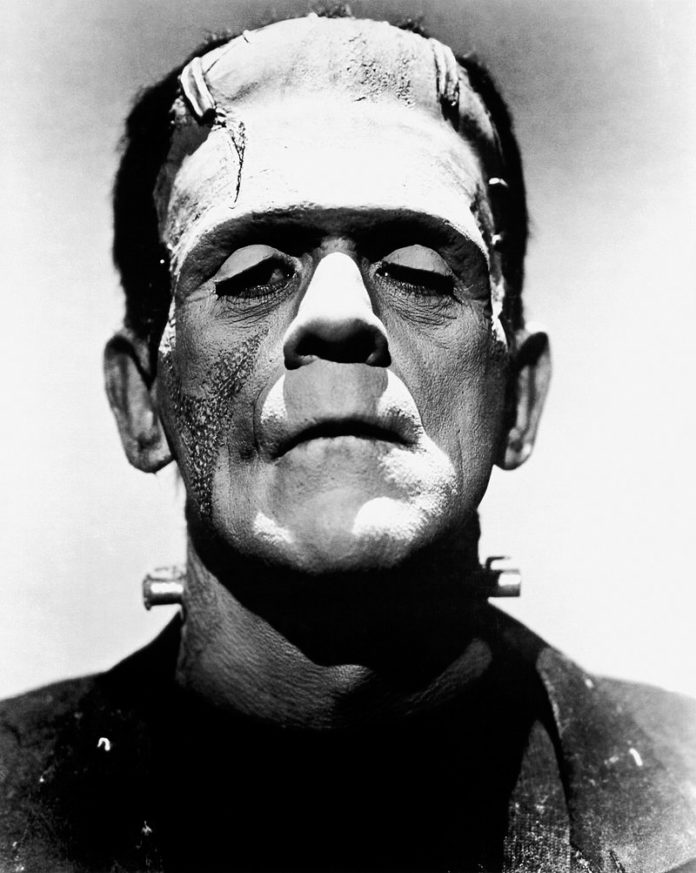

For this Cascade Rewind, we’re really rewinding. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1818, which was 23 years before the stapler was invented. Now, you might think you know the story of Frankenstein: a mad scientist builds a corpse and brings it to life, only for the groaning, green monster to wreak destruction and go on a murder spree. There’s a reason this is a Halloween special. But Shelley’s novel follows a more nuanced, philosophical approach to a creature made from the dead.

It’s true that Victor Frankenstein — more of a college dropout than a scientist or a doctor — robs graves and stitches together a body. But when I first read the book, I was shocked to find that the corpse-come-to-life is presented in a sympathetic light. He’s not a horror movie villain. He’s a creature shaped by his environment — an environment that rejects him at every turn.

In Shelley’s novel, the monster learns to speak English, reads Paradise Lost and other literary works, and conveys arguments that allow the reader to sympathize with him. He speaks in full, articulate sentences. He feels human emotions. And — perhaps his most chilling trait — he’s intelligent. Rather than mindless killing from the hands of an ignorant monster, the novel’s murders are committed with the calculated purpose of causing Victor as much pain as possible.

It might sound alarming that the monster is a calculated and sympathetic killer, but it’s hard to resist pity when he gives long speeches about how he’s been mistreated and rejected by society and his own creator, Victor. In popular culture, the monster speaks only in groans, but the novel’s monster gives us articulate lines like, “God, in pity, made man beautiful and alluring, after his own image; but my form is a filthy type of yours, more horrid even from the very resemblance.”

Maybe Frankenstein feels like horror because of how easily I am swept up by the monster’s sympathetic side. A sob backstory doesn’t excuse horrendous crimes, but here I am, pitying the poor thing, feeling like Victor is more to blame than his creation.

There is a momentous difference between culture’s monster and the novel’s monster. Popular culture presents him as villainous, non-human, one that cannot be reasoned with. Perhaps Shelley wanted to challenge a culture that doesn’t allow for nuance. Instead of simply monstrous, she presents him as morally grey, sympathetic, complex.

And maybe this is a reflection of our culture, that we would rather have a monster that we cannot understand than a monster that we can pity. Because what sort of people would we be if we allowed a monster to speak his mind? It’s much easier to have a Frankenstein who only groans.

Danaye studies English and procrastination at UFV and is very passionate about the Oxford comma. She spends her days walking to campus from the free parking zones, writing novels she'll never finish, and pretending to know how to pronounce abominable. Once she graduates, she plans to adopt a cat.