By Nick Ubels (Cascade Alumnus) – Email

Print Edition: April 9, 2014

“Imagine how you would feel if, when you woke up this morning, you knew that by sunset you would be off the Earth. It changes how you eat breakfast.”

This is how Chris Hadfield began “The Sky Is Not the Limit,” his hour-long address to a North Vancouver audience that covered his incredible journey from awestruck Ontario nine-year-old watching humanity’s first steps on the moon to living aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

The April 4 event was planned as the capstone on UFV’s 40th anniversary celebrations.

The 660-seat Centennial Theatre was filled to capacity to hear the retired astronaut speak. Seniors in formal attire sat next to kids in bright red and sky blue NASA t-shirts, a testament to the child-like curiosity Hadfield inspired throughout his career and particularly during his six-month mission as ISS commander in 2013.

“It’s a million stories,” Hadfield said. “But like most things in life, the great adventure began with some sort of launch, some sort of first step.”

[pullquote]“[T]his is like a tuning fork because everything’s so tightly bolted together. It is rudely powerful. It has 80 million horsepower. It burns fuel at 12 tonnes a second. It’s just a stupid way to get to space.”[/pullquote]

He credited US President John F. Kennedy’s drive to “give people a defiant challenge that was beyond their current capability” for motivating him to become an astronaut. So it was fitting that Chris Hadfield found himself waking up at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida over 20 years ago, ready for his first flight aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis.

The moon landing was a watershed moment not only for a young Hadfield, who would subsequently find himself sitting in his first simulator, a cardboard box he dubbed “Quaker Oats 215,” but for an entire generation.

“It inspired millions of people,” he said. “In the United States, if you track the number of PhDs per capita, it has never in the history of the country been so high as in the years following the original Apollo landings.”

Dedication to a nearly impossible dream influenced every decisions along the path that eventually led Chris Hadfield off this planet. He decided to find a way to realize his goals at age nine (in spite of the fact that Canada did not have a space program) on July 20, 1969, when Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong first set foot on the moon.

“Up until this morning, it was impossible to walk on the moon, but now there are two guys up there. By the time I walked back inside, those guys were sleeping on the moon. How audacious!” he said. “It allowed me a certain confidence that would help me shepherd all the little decisions of my life, that big mess of fractious sheep that is everyone’s actual life, in a direction that may someday get me to the Kennedy Space Center.”

The 54-year-old Sarnia, Ontario native was the top test pilot in the US Air Force and Navy before fulfilling his childhood dream of becoming an astronaut in 1992. Since then, he has lived on the ocean floor, served as NASA’s director of Russian operations, participated in three space flights, and is the first and only Canadian to command a space ship so far. He has been around the globe over 2600 times.

Despite being the most celebrated astronaut in Canadian history, his greatest accomplishment might be connecting with those of us back on Earth. One way Hadfield accomplished this was through a series of simple, but effective tweets. Throughout his mission, he dispatched photos of Earth snapped from onboard the ISS with brief captions that spoke to something universal and human found in the striking imagery.

[pullquote]“There’s a helicopter escort and police out front, police out back, F-15s flying over and you’re kind of at the hub of the maelstrom, and you come around the corner and in the distance … you see your space ship.”[/pullquote]

“I would think, ‘why did that one strike me as beautiful?’” Hadfield said. “We left Earth permanently on the space station; we put our first outpost in space 15 years ago, but you miss it in all the noise. We left Earth. And that’s different than sending out robot probes. That’s humanity changing its perspective on itself.”

It is Hadfield’s keen awareness of the importance of this sort of massive inspiration that led him to share his unique experience with the world.

“I took 45,000 photos because you would too,” he said. “It gives you a different view of the world.”

Hadfield realized the very improbability of human existence, the delicacy with which we survive on the Earth through this lens. One particularly striking photograph captures all five great lakes, one fifth of the world’s drinking water, as “tiny, fragile, temporary puddles on the Earth.”

“You become much more intensely aware of how it all fits together,” he said. “That’s our entire existence, that little bubble [of atmosphere and crust]. We’re all breathing out of the same bubble and yet we treat it like it’s guaranteed, like it’s inevitable.

“We’re the most arrogant goldfish in the universe.”

Last May, Hadfield performed a song live from orbit with over 700,000 Canadian students through satellite feed. He said that taking the time to do these sort of activities was perhaps the most important task of his mission, setting a benchmark about what is possible for the next generation, to show them that “Canadians command space ships.”

Though a pilot and scientist, Hadfield is also an avid musician, quick to note the importance of arts education, a comment that was met with rapturous applause from the packed crowd.

Joanna Wagstaff, CBC weather specialist and host for the evening, aptly summarized Hadfield’s greatest feat: “infusing a sense of wonder into our collective consciousness not felt since the first moon landing.”

Hadfield dedicated a significant portion of his talk to taking the audience on a visceral ride through take-off, landing, and life in space. He described launch day as a mix of the sublime and the crushingly mundane.

[pullquote]“We’re the most arrogant goldfish in the universe.”[/pullquote]

“The day is spectacular, it’s triumphant, there’s horns blaring and fireworks; that’s how it’s supposed to be,” he said. “But in reality, you wake up in this humble little room in quarantine, like it’s a Motel 6 kind of wake up.”

The astronauts are outfitted with diapers and long black socks and fitted into their orange pressure suits before descending down an elevator and into the crew bus driving out towards the launchpad.

“There’s a helicopter escort and police out front, police out back, F-15s flying over and you’re kind of at the hub of this maelstrom, and you come around the corner and in the distance,” Hadfield said, pausing, “you see your space ship.”

It is a dramatic moment when Hadfield first witnessed the Space Shuttle Atlantis sitting on the tarmac, rising above the pre-dawn plains of Florida some 30 storeys.

“It’s probably how the pharoahs saw their pyramids, this beautiful light shining down,” he said. “Yet as you’re driving towards it, everybody else is driving away from it because they realize that it’s a 4-million-pound bomb sitting out there.”

Once the astronauts are settled in the cockpit, the countdown begins. Three-and-a-half minutes before launch, “the vehicle is alive.”

Hadfield showed a clip of the launch sequence, and breathlessly describes the acceleration out of the Earth’s atmosphere:

“It is phenomenally powerful, like the hand of God is beneath you just hurtling you up from the Earth. The vibration is enormous, not like an airliner where you get that sort of slow flopping vibration as you go through turbulence; this is like a tuning fork because everything’s so tightly bolted together. It is rudely powerful. It has 80 million horsepower. It burns fuel at 12 tonnes a second. It’s just a stupid way to get to space.”

Eight minutes and 42 seconds later, after continuously increasing pressure and burning through most of the shuttle’s fuel reserves, Atlantis settles into orbit.

“The engines shut off and you’re weightless,” he said. “How did you get there?”

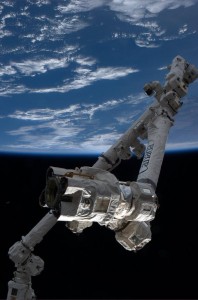

Hadfield cited latching onto an objective just beyond what was currently possible and a spirit of international collaboration between 15 countries who were “enemies within living memory” for coming together to build the ISS. Canadians, too, can claim their contribution with the Canadarm II, which carried out much of the station’s construction. It stands as a testament to what can be accomplished with a common purpose.

“Any kid in the world, no matter where they grow up, can walk outside when it’s dusk or dawn and, when the station is still high enough to be in the sky, watch the brightest star in the sky go from horizon to horizon in about four minutes,” he said. “It’s an undeniable, visible example of what we can do together when we do things right.”

For his part, Hadfield is glad to have had the privilege to travel to space three times. But after 26 years of living abroad, he’s happy to be back in Canada.

[pullquote]“It is phenomenally powerful, like the hand of God is […] just hurtling you up from the earth.”[/pullquote]

“The Sky is Not the Limit” also launched the non-profit Summit Negotiations Society, which plans to use software tools to aid conflict resolution, and a served as a fundraiser for UFV’s new peace and conflict studies program. The night was filled out by preliminary addresses from UFV president Mark Evered and Summit Negotiations Society executive director Elsie Wiebe, a welcoming message from Sheryl Fisher of the Squamish Nation, and a number of honours bestowed on the celebrated astronaut.

The mayors of North Vancouver, Darrell Mussatto and Richard Walton, declared April 4 Chris Hadfield Day, to which the colonel wryly asked whether he could get away with illegal parking now. He was also presented with the World Peace Tartan by its designer, Victor Spence.

The World Peace Tartan has been presented to eight Nobel Peace Prize laureates among other prominent world leaders. This is the first time it has been conferred on Canadian soil. Spence, sporting a vest matching the tartan’s pattern, launched the initiative in December 1999 after an encounter with the Dalai Lama.

Before placing the scarf over Hadfield’s neck, Spence said the retired astronaut’s striking message of our interconnectedness through images of Earth captured aboard the ISS had earned him the honour.

“We create false separateness through a lack of understanding,” he said. “Chris Hadfield took the opportunity to remind us and made an extraordinary contribution to creating that peace on Earth.”

The scarf, which Hadfield wore for the duration of his address, is a beautiful medley steeped in light blue to represent the cooperative promise of the United Nations, with the tartan’s Scottish roots represented in the purple and green of the thistle. Black and red lines represent the realities of war and violence while the white is a counterbalance that symbolizes the hope for peace.