By Katie Stobbart (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: March 4, 2015

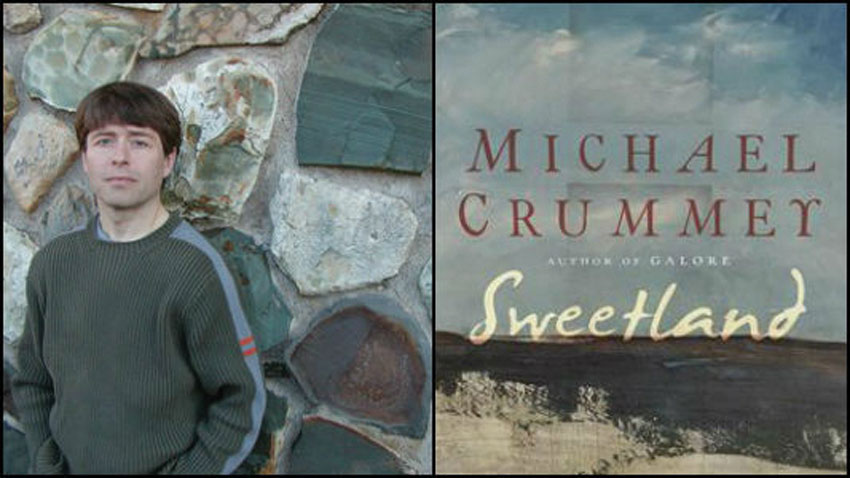

The ideas behind Michael Crummey’s Sweetland are intriguing. I knew before flipping to the first page that it would feature a retired Newfoundland lightkeeper living in total isolation on an uninhabited island. I knew he would be separated from the central characters in his life, that he would have a particular relationship with the place he lived, and that he would struggle to survive cut off from the rest of the world.

Yet the story doesn’t go much further. The book is split in two equal chunks of narrative — pre- and post-inhabitation of the island called Sweetland — with the main character, Moses Sweetland, not reaching that state of isolation until the second half. A few scattered subplots are threaded into the bifurcated storyline, ends sticking out askew.

I had some criticism for Crummey’s last novel, Galore, but overall the structure was reasonably effective. Here the sprockets — structure and synopsis — don’t quite mesh. The reader spends the first half of Sweetland wondering when we’re going to get to the “good” part, while searching for reasons the characters matter in the grand scheme, and the second half wondering why the story didn’t start here, why we needed so much preamble.

The real meat of the tale is the question of Sweetland’s sanity; while the structure suggests Crummey might intend to establish contrasts by demarcating the beginning of that mental shift, it would have been more effective to compare lucid moments with fractured ones, to raise that question in the reader: which are real? As it stands, that question falls flat; the element of surprise is lost before it can be invoked.

The characters have their moments, and I enjoy their authenticity; they don’t pigeonhole easily. Ultimately, though, their quirks do not make them unforgettable, and moments in their lives that should have been charged with emotion felt curiously distant, almost unmoving except when Crummey adds shock value (mutilated rabbits and ocean-brined bodies, for instance).

Sweetland is almost comically unprepared for self-imposed isolation; perhaps there’s a point Crummey is hoping to make somewhere in that, the idea that none of us today, even a supposedly sea-smart and gritty geriatric, could do without electricity, internet, plumbing (but wait, there is running water somehow?), and community. Still, if his aim is not to die anytime soon — and it doesn’t seem so — I have a hard time with a man who buys scant supplies and tends a vegetable garden, but doesn’t ensure he has a decent fishing vessel or comprehensive supply of canned goods and ends up having to use old Harlequin pages (wink, nudge) for toilet paper.

I wish I could say these problems were redeemed by flawless prose, that Crummey brought his poetic sensibility out to play, but frankly the writing was not as strong as I expected, either. Fragments and splices were distractingly prevalent, Sweetland’s internal voice and the narrative vernacular seesawed between the fisherman (Sweetland) and the academic (Crummey), and every bit of Newfoundland slang (even words I liked upon first use, like “glim”) dried of its original sheen from overuse.

In an article for CBC Writes, Crummey said he had no organizational devices when it came to writing Sweetland, that he just sat down and wrote without referring to his notes, and liked the way it turned out on the page.

Unfortunately, the result is a novel that feels poorly structured, unrefined, and like a disappointing example of what Crummey is capable of — a step down rather than an improvement on his last work.