The Canadian federal government will release a new nutritional guide for Canadians early this year, containing many changes from the previous version. The new nutritional guide is not yet confirmed, but a sample version used in focus groups reveals details about what it will contain and how it is organized.

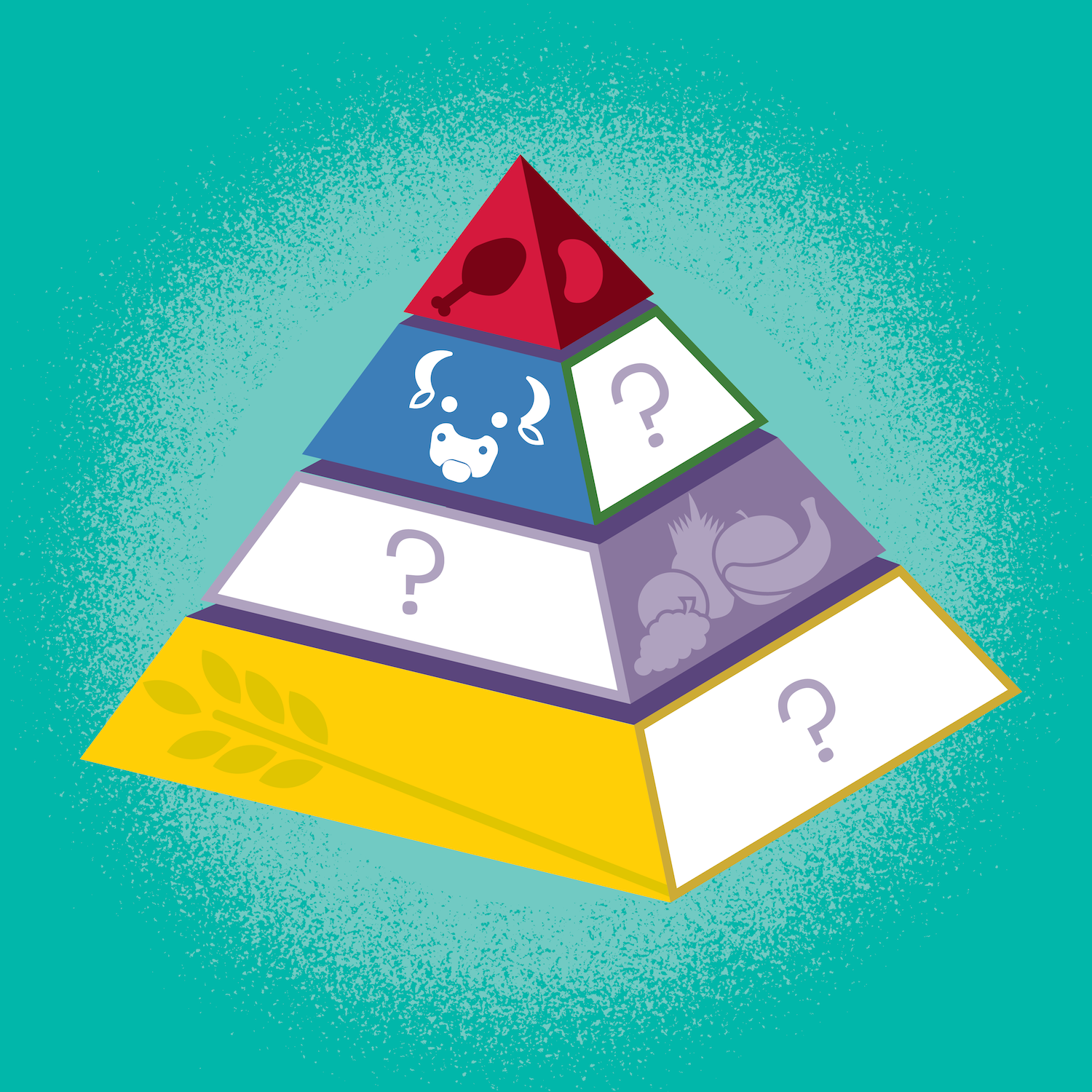

The familiar “food rainbow” of the previous guide sorted foods into one of four categories: grain products, fruit and vegetables, dairy and alternatives, and meat and alternatives. This will apparently be done away with in the new guide, according to the focus group document, with plant-based foods given greater emphasis, meat further reduced in importance, and dairy nearly eliminated.

This preview has attracted the ire of Agriculture Canada, and dairy and livestock industry lobbyists who take issue with the new guide recommending plant-based proteins as a substitute for meat and dairy. The lobbyists claim that this will hurt Canada’s agricultural industries, which are allegedly already suffering from recent foreign trade concessions. They also fear that the new guide will create “confusion” about the healthiness of dairy products, according to a statement mentioned by Global News.

Despite this, Health Canada has vowed to rely solely on independent and internationally-recognized nutritional studies as the basis for the new guide, which has been in the making for some years now. It is comforting and gratifying to see a government willing to put the health of their citizens above satisfying private industry interests, especially when that government is our own. I for one applaud Health Canada’s willingness to stick to their guns and not allow the lobbyists to dictate policy. That being said, I sense there is more at work here than mere nutrition.

Cultivating livestock is much more resource-intensive than doing the same with crops, in part because additional crops must be grown to feed the livestock. Methane expelled by farm animals, especially cows, is also believed to be a major source of greenhouse gases. In addition, animal feces can seep into groundwater supplies, resulting in contamination. In this time of resource shortages, climate change, and environmental degradation, I suspect the guide’s recommendations are designed at least in part to reduce demand for foodstuffs that are environmentally costly to produce.

Multiculturalism and inclusivity may also play a role. It occurs to me that the assumptions of the old guide are somewhat Eurocentric. European cuisine (especially northern European) traditionally makes heavy use of meat and dairy, and so Europeans have developed a tolerance for high-fat foodstuffs. Among most East Asian peoples by contrast, lactose intolerance is the norm rather than the exception. A meta analysis conducted of 62,910 participants from 89 countries found that 64 per cent of those in Asia experienced trouble absorbing lactose, as opposed to 4-30 per cent in Northern and Western Europe. The new food guide may be an attempt to be more aware and inclusive of those with dietary restrictions (such as allergies, religious taboos, etc.) since plant-based foods are generally a safer bet in these situations.

With regard to nutrition itself, the dairy farmers may have a point about confusion. The part of the guide revealed to the public listed specific foodstuffs that one ought to consume on a regular basis, but it gives no indication of how much of each is recommended. Also, meat and dairy are not necessarily unhealthy. Milk is an excellent source of calcium, and certain nutrients like iron and vitamin B12 can be difficult to acquire without resorting to eating meat. Conversely, plant-based foods are not always healthy. Gluten from grain products is known to cause problems, especially, but not exclusively, for those allergic to it.

In the end, I don’t think the new food guide will have much influence on the foods we eat. Our food choices seem to have more to do with personal preferences, cultural tradition, and the cost and availability of ingredients. Where the new guide will likely have the most impact is in how we see our food, and our concept of a balanced diet. My generation was taught to classify food into the four basic groups (with possibly a fifth for junk food), and that as a rule of thumb, one should try to consume some of each on a regular basis in order to lead a healthy lifestyle. The new nutritional guide will change those assumptions and the way we look at food, if not what we actually eat.

Image: Cory Jensen/The Cascade