by Nick Ubels (Online Editor)

In 2005, singer-songwriter Sufjan Stevens catapulted to international attention and critical recognition well beyond indie circles with the release of his landmark paean to the people, places and history of the Land of Lincoln, Sufjan Stevens Invites You To: Come On Feel the Illinoise! or simply Illinois. The meticulously researched, extensively orchestrated and affectionately crafted collection formed the second album in what Stevens claimed to be a forthcoming series dedicated to each of the 50 U.S. states, beginning with Michigan, his 2003 LP.

To be fair, few expected Stevens to complete such an ambitious project. Even if he released a new album in the series each year, he would be well into his 80’s before it was finished. A tall order considering Sufjan’s auteur-like approach to recording; not only taking on the responsibility of composition and arrangement, but much of the performance and production duties as well.

Fans frequently guessed at which state Stevens would tackle next, fuelled by online rumours that suggested California, Rhode Island, and Oregon among others. In a footnote to a 2007 essay, “Friend Rock,” the folk musician mentioned that he was reading a biography of famous New Yorker Robert Moses, setting off speculation that he was working on an album about New York.

Yet as the years passed with little concrete evidence of another state-inspired album on the way, a dwindling number of fans still desperately clung to the hope that the 30-something Michigan native would return with another addition to the beloved series.

Those hopes were effectively laid to rest when Stevens publicly distanced himself from the project, stating in an October 2009 interview with The Guardian, “I have no qualms about admitting it was a promotional gimmick.”

In the five years since his last full length album of original material, Stevens has remained mostly out of the spotlight, making a handful of live performances, releasing a series of Christmas EPs, spearheading 2007’s The BQE multi-media presentation, contributing to a long list of albums including The National’s High Violet and at times publicly questioning the point of recording new albums. Yet it seems that he has found inspiration at last by looking within for his latest LP.

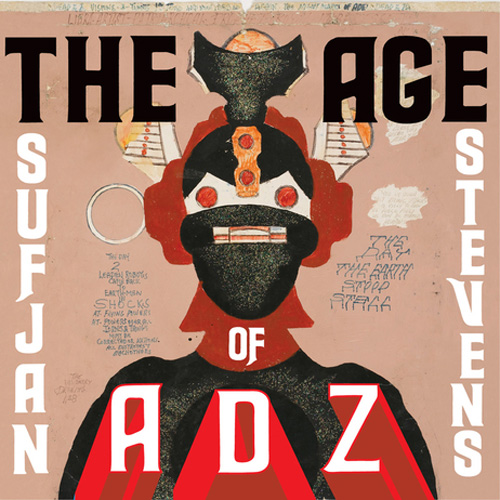

Stevens’ sudden digital release of a 60-minute “EP” entitled All Delighted People on August 20 followed by the announcement of an upcoming full-length album a few days later shocked scores of fans who did not expect such an outpouring of new material from the semi-retired singer-songwriter. The album, entitled The Age of Adz, is an equally shocking experience for long-time listeners.

The new album, streaming live at NPR.org until its October 12 release, opens with “Futile Devices,” a muted, mostly acoustic rumination on unexpressed love that comes far closer to the musical style of Stevens’ earlier work than anything else found on Adz. Nevertheless, the song firmly establishes the vulnerable, introspective mood further explored in the rest of the album, albeit through a haze of twitchy, buzzing electronics.

Track two, “Too Much,” is the first taste of what is to follow. This seven-minute tour-de-force opens with squelches of psychedelic synth feedback reminiscent of The Flaming Lips that gives way to a fuzzed-out drum machine back beat that lurches the song forward through at least five distinct sections of intricately composed electronics and orchestral flourishes before coming to a chaotic, thundering conclusion.

Elsewhere on the album, Stevens mixes familiar elements such as choral backing vocals, fluttering woodwinds and triumphant horns with hip-hop beats (“Age of Adz”), extensive vocal manipulation (“I Wish I Was Well”) and even Auto-Tune on the album’s sprawling, epic 25-minute coda, “Impossible Soul,” as he successfully deconstructs his trademark sound.

“I’m sorry if I seem self-effacing, consumed by selfish thoughts,” apologizes Stevens on the title track, capturing the disarmingly personal tone of the record. Where the singer-songwriter once expressed himself through narratives and character sketches, he is refreshingly direct here in his most personal album to date.

Whatever the genre, Sufjan Stevens retains his folk ethos in the intimacy of his songwriting. While some may feel alienated by Adz’s new emphasis on electronics, others will connect to the very personal feeling of alienation articulated by Stevens both lyrically and musically in this collection. It is the first of his albums to forgo any sort of rigid, conceptual basis, allowing the musician a new freedom of expression.

No longer weighed down by the expectations of an immediate follow-up to a critically acclaimed concept album, The Age of Adz is a compelling reinvention that finds Sufjan Stevens at his most uninhibited and inventive. And that is a great place for any artist to be.