By Nick Ubels (The Cascade) – Email

Date Posted: October 17, 2011

Print Edition: October 12, 2011

I heard a faint olé

I heard a faint olé

True love but

I had other ways to hurt myself

Garbled, percussive low-end rumbling squelches and fades over Glenn Kotche’s insistent and elliptical drum riff. Like a radio dial slowly zeroing in on the correct frequency, electronic blips and odd, disquieting instrumental flourishes flare up and die, gradually overwhelmed by a swell of polymorphic strings and pulsating keys that pull back in turn to reveal vocalist Jeff Tweedy’s nakedly-honest inner monologue.

“No! / I froze / I can’t be so / Far away from my wasteland,” he sings in his shaky tenor with little accompaniment to hide behind. It is a brief, boldly vulnerable expression of self-doubt and an anxiety-ridden reflection on the weight of constant creative and social imperfection that is soon joined by Kotche’s now familiar drum pattern and an impossibly funky bass-line from John Stirratt.

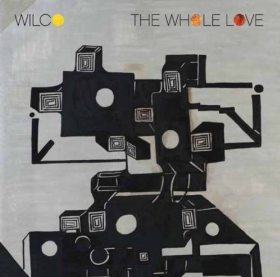

It is this expertly crafted, genre-defying concoction that opens The Whole Love, Wilco’s eighth studio album and the first on their own dBpm Records imprint. First impressions have always been one of the band’s greatest strengths and the seven-minute “Art of Almost” is no exception.

Opening tracks from throughout Wilco’s 17-year career have inevitably served as defining statements-of-intent for each era. The Chicago band has seldom shied away from placing their most alienating and experimental work at the front of each of their albums, the one notable exception being “Either Way,” which served as a breezy and benign introduction to 2007’s mostly breezy and benign LP Sky Blue Sky. While “I Am Trying To Break Your Heart,” immediately brings to mind the numb and fractured noise pop of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, “At Least That’s What You Said,” captures the passive aggressive minimalism of A Ghost Is Born. These songs have all done their part to reassert the importance of the album in the era of shuffle-ready singles by establishing a certain frame of reference that informs the listener’s experience of the songs to follow.

“Art of Almost” is challenging, messy, and disorienting, but it works because its more experimental elements remain rooted in a fundamentally melodic instinct and lyrical sincerity. It sets up an album marked by a return to the sense of discovery and confident experimentation that made Wilco one of the most exciting and progressive post-millennial American bands, but has been sorely absent on the band’s most recent efforts.

Unlike the aforementioned Sky Blue Sky or 2009’s goofily self-aware Wilco (The Album) which does a passable job of summing up the band’s career thus far, Wilco’s latest pulls off the impressive task of seeming at once effortless and adventurous. Their last two records only succeed on one of these fronts respectively. Sky Blue Sky feels natural, but complacent and lags in places. Wilco (The Album) is more interesting musically, but seldom moves beyond its stylistic trappings.

Variety and risk-taking are hallmarks of The Whole Love; its weakest track, the rambling, vaudevillian “Capitol City,” still features a few offbeat instrumental choices. “I Might,” is a vital and energetic acoustic guitar and fuzz-bass propelled track replete with shimmering organs, bells, playful backing vocals and a frenetic guitar line courtesy of a less obtrusive Nels Cline while mesmerizing album closer “One Sunday Morning (Song for Jane Smiley’s Boyfriend)” finds Jeff Tweedy in shuffling folk balladeer mode. Elsewhere, “Dawned On Me” boasts Wilco’s most affecting pop chorus/bridge combination since Summerteeth.

These highlights prove that Wilco is still able and willing to surprise. The current line-up is now the longest-running in the band’s history and that consistency is finally beginning to pay dividends. Nels Cline and the band’s other recent additions no longer stand out in the manner of talented, but un-invested session players; instead, they seem to work first and foremost in the service of the song. The Whole Love may not be perfect, but it is a heartening return to the sort of artistic restlessness that has produced Wilco’s most compelling work.