Print Edition: November 2, 2011

In a sea of makeshift placards held above the heads of their authors, one particular message etched a lasting impression in my mind as I waded through the crowd at Occupy Vancouver: “If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention!” It is with this notion that I want to share what I’ve learned about the Occupy movement – an issue that didn’t end with the initial protests but rather grows, strengthens, transforms and perseveres.

In a sea of makeshift placards held above the heads of their authors, one particular message etched a lasting impression in my mind as I waded through the crowd at Occupy Vancouver: “If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention!” It is with this notion that I want to share what I’ve learned about the Occupy movement – an issue that didn’t end with the initial protests but rather grows, strengthens, transforms and perseveres.

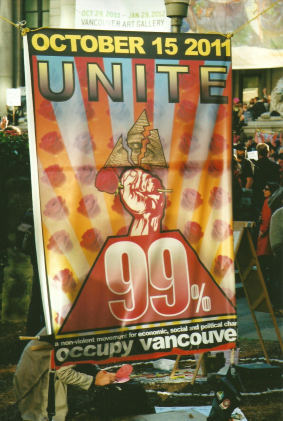

Since September 17, Wall Street has been the setting for a gathering of frustrated Americans, voicing their outrage about economic, ecological and social injustices. On October 15, the rest of the world joined in, flooding each city’s public venue of choice to express mass discontentment. Many thousands of citizens continue to occupy hundreds of cities globally.

Traditional media outlets have struggled with their coverage of the movement. Initially, they ignored what was happening completely; but as alternative, digital forms of media began to spread the word, newspapers and television broadcasters became obliged to make mention of the quickly growing campaign. However, the traditional requirements for media—to compress all events and issues into brief summaries—cannot properly address such a multifaceted demonstration. In abandonment of the examination required to properly dissect and accurately report on the Occupy movement, many newspapers and TV personalities sum up the issue by accusing it of ambiguity and lacking focus, instead. Firsthand experience with the demonstration, however, makes these claims seem impetuous – and the movement does indeed have relevance and legitimacy.

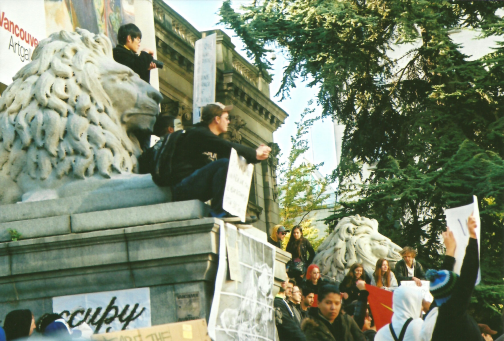

I first attended Vancouver’s demonstration on the day it began. As I approached the crowd on the lawn of Vancouver Art Gallery, I immediately noticed that the demographic of the occupiers was more diverse than I had expected. There were many grey-haired elders, middle-aged professionals, young families, and, of course, the 20-somethings the movement has been identified with. The face that has been attached to Occupy since it began has been that of an out-of-work, student loan-laden, desperate youth; it is comforting to know that the outrage touches those beyond a single demographic. A scan over the crowd made it clear that this is the people’s movement, not the young people’s movement.

Walking through the gathering, I was struck by the incredibly joyful atmosphere. Wide smiles were found on many faces between the bobbing signs; hula-hoopers played on the barricaded street; strangers acknowledged one another in a way never seen on this intersection of Howe and Georgia. A smaller crowd happily danced to a group of drummers pounding out a mesmerizing beat – even the police officers watched with content amusement from the perimeter. The sense of community that had been established in those first few hours was profound.

It must be noted that the event wasn’t one to be witnessed; it was to be participated in. The voice of every attendant was equally valued. As a speaker took the microphone, a simple system of hand gestures allowed every person in the crowd the opportunity to show their approval or disapproval, to ask a question, or to respond. The process was respected, and a collective discourse took place throughout the day, discussing a variety of injustices and possibilities for change. Through this dialogue, citizens were given a method of constructively sharing their opinions. A large-scale, productive public forum sprung up overnight – a vital component of effective democracy.

I happened to see a familiar face, UFV English professor Trevor Carolan, stopping to read the many messages adorning the sign-making station. I caught up with him later in his office at UFV to ask him to respond to the question that’s been asked since the movement began: what do the “occupiers” want?

“What they’re wanting is social justice,” he explained. “They want an end to social and political segregation… [and] they’re looking for a form of sustainable living that’s founded on sustainable economic order.” He added that there will, of course, be regional differences.

Carolan clarified that the movement is “still a conversation – a communal conversation… [and] the challenge is going to be whether the beginnings of this movement morph into something larger and more collective.”

“At last, it’s the rise of participatory democracy,” he added. We certainly hope so.

As I took a seat on a bench just beyond the perimeter to load a fresh roll of film into my camera, I overheard a nearby elderly man blurt to his companion as they watched the emotionally-charged mass of demonstrators: “They don’t know how good they’ve got it.” This struck a chord with me, because it was an outlook I had struggled with myself as the movement initially gained momentum. After all, the motto “We are the 99 per cent” means one thing when referring to Canada, the United States, or North America – but when we consider society on a global scale, some attendants of Occupy Vancouver are more likely in or at least nearing the 1 per cent bracket. This causes us to ask whether we, the wealthier portion of the world’s population, are in any position to protest our circumstances.

My internal debate was settled once I attended the event and noticed that the demands adorning signs on sticks and the conversation amongst provoked citizens are not founded in self-interest. In most cases, they are not asking for more privileges for themselves, but are intervening on behalf of those less fortunate. The conversation, and the demands that will arise from it, are ones for the collective benefit of our world, not just to serve the personal wishes of the occupiers. One sign displayed the message “We! Not me!” – a common sentiment. The smiles indicated that this crowd does know how good they’ve got it, but they are conscious that there are many who don’t enjoy the same privileges, and that there is ample room for improvement in their own circumstances as well.