By Alex Watkins (The Cascade) – Email

Date Posted: September 1, 2011

Print Edition: August 25, 2011

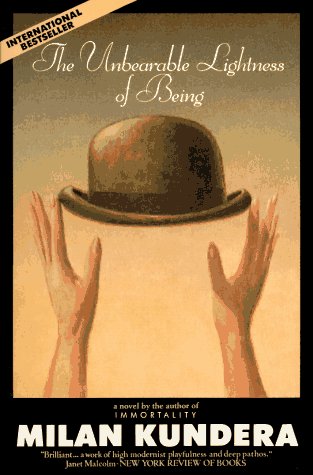

Milan Kundera is a singularly inventive and interesting author, and his most famous work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, is an exemplary illustration of the deftness and wit which has brought me wholeheartedly into his camp.

Milan Kundera is a singularly inventive and interesting author, and his most famous work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, is an exemplary illustration of the deftness and wit which has brought me wholeheartedly into his camp.

The novel explores relationships, human desire, and the capacity for love (both human and animal), but it’s not just all hearts and flowers – he also delves into the nuances of philosophy, music and literary composition. Kundera can stir up sympathy and wistfulness on one page and shock and horror on the next, but even more impressive than his range is the fact that all this is accomplished with the guiding voice of the author, who continually breaks through the wash of what could have been just another love story with interjected musings on the events and ideas that breathe life into the characters themselves – people who, as Kundera reminds us, “were not born of a mother’s womb… [but] of a stimulating phrase or two from a basic situation.” The reminder of the author’s presence nudges the sole focus off of the workings of his character’s lives and onto the greater topics that he wrestles with, perhaps most prominently, the opposition of lightness and weight.

This opposition is introduced within the first few pages as an offshoot of Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return – the notion that every experience could recur infinitely, and that the knowledge that these actions recur would lend more weight to them than if they were a mere fleeting occurrence in the kind of linear history we are accustomed to. If recurrent actions have “weight,” then actions that only occur once – the kind we are familiar with in our world – are transitory; they have “lightness.” Weight, as he explores, ties us to our earthly being, while lightness releases us from it, making it seem inconsequential. But knowing this, he asks, which is better: lightness or weight?

Characters continually deal with this opposition between lightness and weight, struggling to craft something enduring and meaningful in a life that is only lived once and is therefore passing and insignificant. Tomas, protagonist and lifelong philanderer, is an ideal illustration of lightness, having rid himself of his ex-wife, their son, and, along the way, his parents, until he is confronted with the cumbersome, needful love of one of his chance conquests, Tereza. She drags her “enormously heavy” suitcase into his apartment and a weightier kind of romance into his life than he has ever known. And though Tomas, despite his love for Tereza, can never give up his many “erotic friendships,” he also cannot let her go. In this sense, the lightness of being is made unbearable after moments of true weight are experienced and when Tereza briefly leaves Tomas, what would once have seemed to him the perfect, symmetrical and pleasingly literary closure to their love affair (and the glad reawakening of his unfettered bachelorhood) now seems tragic, and he follows her. Tomas forsakes the lightness of his dealings with numerous women for the heaviness of Tereza’s steady and dependent love.

Kundera also explores the German notion of “kitsch” – defined as “the absolute denial of shit, both in the literal and figurative senses of the word; kitsch excludes everything from its purview which is essentially unacceptable in human existence.” Sabina, the best and closest of Tomas’ erotic friendships, devotes her life and her art to the eradication of kitsch, preferring to reveal the weightiness of what lies beneath this “mask of beauty.” Sabina’s style of painting, favoring “double exposures” wherein the smooth and perfect “intelligible lie” of the surface is flung off by the seamier “unintelligible truth” hiding beneath, reflects Kundera’s own approach of penetrating mere sentimentality and posturing by calling attention to the art form itself, and all the artifice that goes with it. His style makes the presence of the writer as visible as what lurks beneath the surface in Sabina’s paintings.

With all respect to that behemoth of German philosophy, as I read I couldn’t help but consider the possibility that, contrary to the initital Nietzschean proposition, the absence of eternal return did not seem to make the characters’ decisions insignificant (at least merely in the scope of their own lives) but rather more precious. Indeed, it makes the contemplation of the other, unchosen roads seem insignificant – as we can never know for sure what could have been – but the choices faced and decisions made are weighty because there will only be one opportunity to make them.

But could this idea, too, be dismissed as kitsch? Could my belief that events in some single, transitory life can hold importance be mere evidence of my own experience with this triumph of emotion over reason – a “folding screen set up to curtain off death?” Kundera, you wily fella, I suppose I’ll have to revisit you again and decide.