By Christopher DeMarcus (Contributor) – Email

Print Edition: October 9, 2013

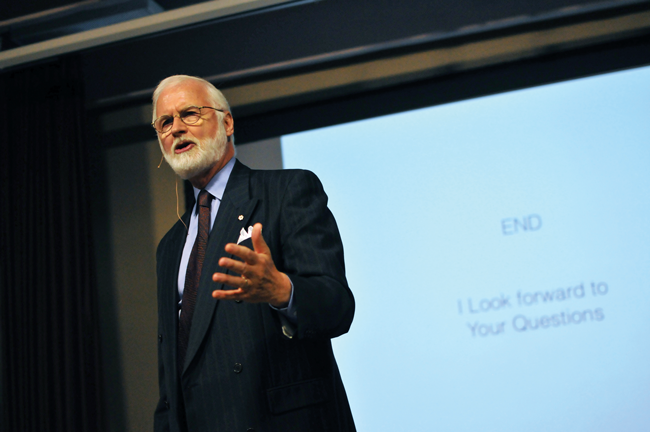

Robert Fowler has had an epic career. After starting out as a teacher in Africa at the age of 19, he joined the Canadian foreign service. He has been the Canadian Ambassador to Italy and the UN, Deputy Minister of Defence, and Foreign Policy Advisor to three different prime ministers.

On top of that, Fowler and his colleague Louis Guay were kidnapped by al Qaeda in 2008 while working for the UN in Niger. Their captors drove them deep into the Sahara Desert where they held Fowler and Guay for over four months.

On October 2, in response to an invitation by UFV political science professor Edward Akuffo, Fowler came to UFV to speak with students about his experiences. There were many topics to cover: international law, economic aid, terrorism, religious extremism, and of course, Canadian foreign policy.

What’s your advice for students who wish to get into the Canadian foreign service?

It’s not as easy as it used to be. When I applied they were looking for people. Now people are looking for them. I had one degree: a BA in art history. Today, it’s highly competitive. Our government isn’t as engaged in foreign policy as it used to be, so there [are fewer] foreign service jobs. I believe that last year they hired less than 20 people, if any at all. They require more credentials, at least two degrees. About 8,000 will apply, maybe 20 will get hired. Only 400 of the 8,000 will be interviewed. How you get an interview is pure luck. It’s a significant crapshoot. It also depends on how well you get along with the hiring board. Do they like you? Are you someone they want to spend a lot of time with?

How has Canadian foreign policy changed over the years?

There are four times more countries in the UN today than when it started in 1945. Canada is less of a big player because the membership has expanded. We used to be in the top rank of peace keepers – now Canada is the 58th most important peacekeeper. Our military strength has declined. During WWII we had around 1 million troops. We were a major military power. Today we have 70,000. Our procurement process for new hardware has become much more politicized and complex. For example, we build frigates in Quebec and New Brunswick, then we try to fit them together. We want to punch above our weight, but the reality is we punch below. There just isn’t enough money to get it all done. If there ever was a “golden age” in Canadian foreign policy, I caught the end of it.

What were some of the policy errors made in Afghanistan?

Foreign policy is a mixture of security interests, development, and values. The more a country talks about values, the more I distrust them. What we were trying to do was turn Afghanistan into Alberta. We [western powers] had poor war aims. We wanted to fix everything in our own way. You can’t change the values of extremists. They’ll wait you out.

When Mr. Obama announced a 30,000 troop surge, he also mentioned a timeframe. He said that in a year-and-a-half the troops would come home. The Taliban will wait it out. They are religiously dedicated. Time doesn’t mean the same thing to them as it does to us.

You’ve spent the majority of your life working in Africa. It seems that Africa functions as a symbol of charity in our culture. What do you think of the commoditization of aid to Africa?

It’s a dilemma. NGOs can be big business. There are some good NGOs and there are some bad. One of the problems right now is that NGOs are not regulated as much as other businesses. At the same time, we need them. If you’ve read Dambisa Moyo’s book Dead Aid, you know her thesis, that imperial forces have created a system of aid that makes African states reliant on the aid of wealthy states. And it’s true, there is an imperialistic aspect to aid. But the World Food Programme fed hundreds of millions of people last year. I don’t pretend to have the answer. How we give aid is a problem that we need to be more creative at solving.

Do you think terrorism is a real threat?

Absolutely. It is the threat of our time. And extremism is growing.

In your book, you describe the members of the al Queda cell that held you. Some of them went to school in France and spoke several languages. Do you think that more education and development is a good way to fight terrorism?

Development is important, but most terrorism comes from religious extremism. When I was kidnapped, it wasn’t about getting more development, it was about [for my captors] Islam. Yes, some of them were educated with bachelor laureates from France. Some were well-travelled. The camp leader, whom I call Omar One, spoke several languages. What made them extreme was their radical religious convictions, not a lack of education. They don’t want development. They want jihad.

I was ashamed about what I knew about Islam before I was kidnapped. My captors didn’t know much about Islam either, but by God, they knew what they knew! They were fundamentalists. They were jihadi. When I spoke to them about things I had to come at it through a religious method.

They were technically agile with smart phones, laptops, and GPS. At the same time they absolutely detested the concept of flexibility. They knew that their view was right and they didn’t care about what they didn’t know.

The cultural gulf was enormous. There was no fun. At no point was my interaction with them friendly. It was all business.

When I was leaving the camp, Omar One told me, “Tell them that I did everything to save you.” “Tell who?” I asked. “When you die, tell the angel Gabriel that I did everything I could to convert you. Tell them you chose to not be saved. Tell them that it was not Omar’s fault!”

What makes someone go radical? How do we prevent extremism with policy?

I don’t know. One idea is to lean on the Saudi princes that fund terrorist cells, to stop the radical poison that is being pumped into children’s heads. Many of the jihadis are sons of devout families that have been given to the cause by their parents. Kind of like how large families used to give one son or daughter to the church, to become a priest or nun. The difference with al Qaeda is that they’re getting fitted for a [suicide] vest.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

With files from Chris Kleingertner.

A Season in Hell: My 130 Days in the Sahara With al Qaeda

Robert Fowler has written A Season in Hell: My 130 Days in the Sahara With al Qaeda, a book which covers his nerve-racking captivity. The account is a bold narrative about how the clash of civilizations plays out in real time with real consequences. It is essential reading for anyone who wishes to learn about Islamic terrorism.

What has made Fowler’s book work is its core perspective of observation. There isn’t a lot of complicated discussion about cultureal relativism or moral ambiguity. Instead, Fowler has written a clear account. His vivid descriptions journey through both his external environment and internal personal trauma.

Throughout the book’s 340 pages, Fowler lays out an even-paced, chronological narrative. In contrast, his captors do not have the same sense of time. While Fowler operates on a strict day-to-day schedule, the terrorists see time as relative – they are completely focused on their extremism, not the dials of a clock. The perception of time in the book is a key indicator of how different Fowler’s culture is from that of his captors.

Pushing the story along, the cultural divide makes for strenuous negotiations. The extremists are committed to a black and white way of thinking. The grey areas of negotiation process—of give and take, conceal and reveal—don’t go over well with al Qaeda.

Beneath the surface of the thriller-like memoir is a constant need for judicial prudence. The ambassador works through mind-numbing fear to clarify and understand his predicament. Physical damage takes a toll, too. Fowler’s back was heavily damaged while being transported from Niger into the vast deserts of northern Mali. He couldn’t lie down. He couldn’t sleep. Yet, he and his fellow hostage Louis Guay were focused on survival and empirical analysis.

Fowler clearly expresses how al Qaeda is dedicated to a cold and brutal ethos. They are an absolute threat to human security and Fowler’s life. But at the same time, the book never feels demonizing. While obviously critical of the ideals of terrorists, it respects them as a real threat – worse than monsters under the bed.