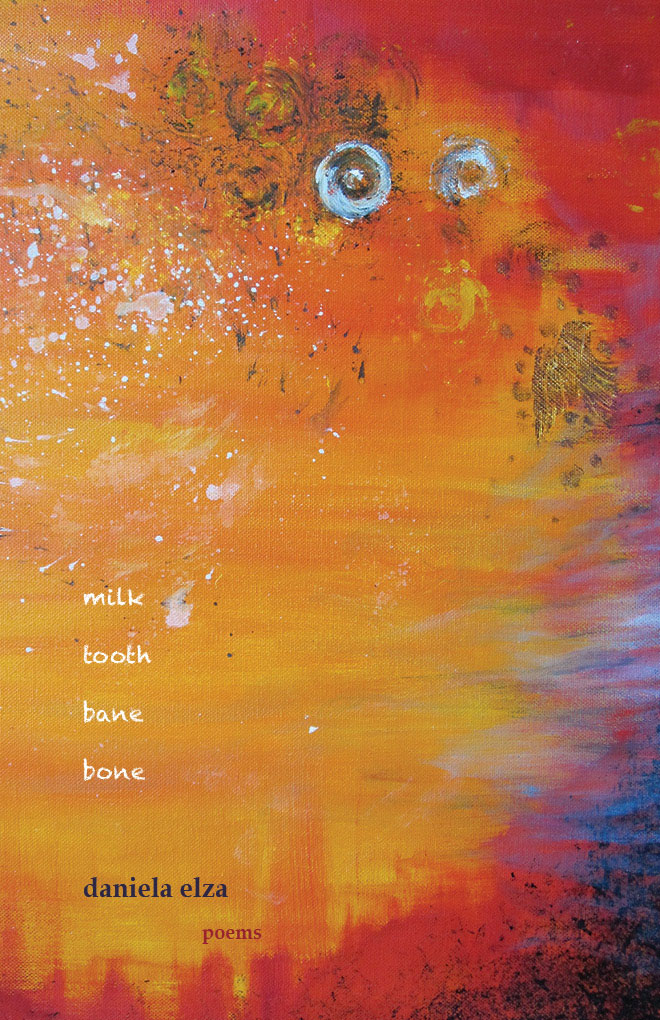

Print Edition: January 29, 2014

“How does it start? Read me the first line,” a colleague said, spotting my copy of milk tooth bane bone on the desk. Another coworker balanced the book in her hand, turning to the first poem.

“Today, a crow flies up,” she read. The response was a smile.

“That sounds like a ‘Katie’ book.” Maybe because I love poetry, maybe because I have been vocal about my feelings on crows, of being haunted by them. Either way, Daniela Elza’s most recent collection of poems resonates with me on a personal level. It attends to the curious blend of fascination with and fear of crows I’m sure many of us feel at some time or another, and to their insistent presence in our quotidian mythologies. Although Elza never explicitly states, “This is what crows are. This is what they mean,” her poetic exploration in milk tooth bane bone implies there is an answer. In many ways, the collection recalls Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” not just because the subject is the same, but due to its pure, emotive ambiguity, and because to understand it means looking deep into the eye of mystery — of feeling something rather than trying to logically justify it. Elza takes it further: she gives us hundreds of crows, murders of them. She observes their patterns, their strangeness, and their familiarity. She explores the tight weave of two narratives: the crows’ and our own.

“We look at each other

sideways crow & I

for an instant agree—

this kind of

sustenance is miserable.”

The collection is at once a product of obsession and philosophy, resulting in both mythology and truth, by means of both language and the unsaid — perhaps the unsayable. Yet it is concrete. We see “dendrite reflections of trees” and the flash of sunlight on a black wing. The poems are intimate, too; the speaker’s personal history is spread open, laced with crows.

I read the poems aloud as I walked to work early in the morning — you can’t walk anywhere here without seeing them. At times the reading was difficult; through unique use of punctuation and italics Elza captures the nuances in language, coaxing the words within words to emerge (sinew and ripples and skin), and opening up spaces in language which are unpronounceable with a singular voice. Perhaps it is this layering of meaning that makes each poem in milk tooth bane bone feel like part of a mythology. Elza also uses parentheses in a distinct way — she will open them without closing them, for example. The spacing of words on the page also affects the ways the words can be read and the poems are full of movement. I don’t believe they should be read a certain way; Elza’s choices in language are all about possibility, not rigidity.

The poems themselves are characters in this curious myth.

“Words are lumps of coal come alive. they spread their wings

and fly off into the night.”

Throughout the book Elza explores the links between the crows, the poems, and the elusive feathers of memory that construct an ideology.

“I gave my teeth to the crows

and they have not left me alone.”

In a way, my colleague was mistaken. This is not just a book for someone who already loves poetry, or whose mind is preoccupied with birds. Milk tooth bane bone is about presence, about seeing the mysterious life of the seemingly ordinary entities around us. It is an attempt to understand what we do not have adequate words for, and it is a reminder that we are not alone. It explores symbiosis. And more still. Most importantly, I think, it tells us to be attentive.

“An instant’s sleek shadow

across my face

pecks a memory

out of my eye,”

To me, this articulates the idea of consciousness. How many moments like this do we ignore? Milk tooth bane bone is insightful, philosophical, and mindful. It is a book worth reading, but more than that, it is a book you live with, you eat with, you walk to work with, and each time you take something new from it.