By Valerie Franklin (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: June 4, 2014

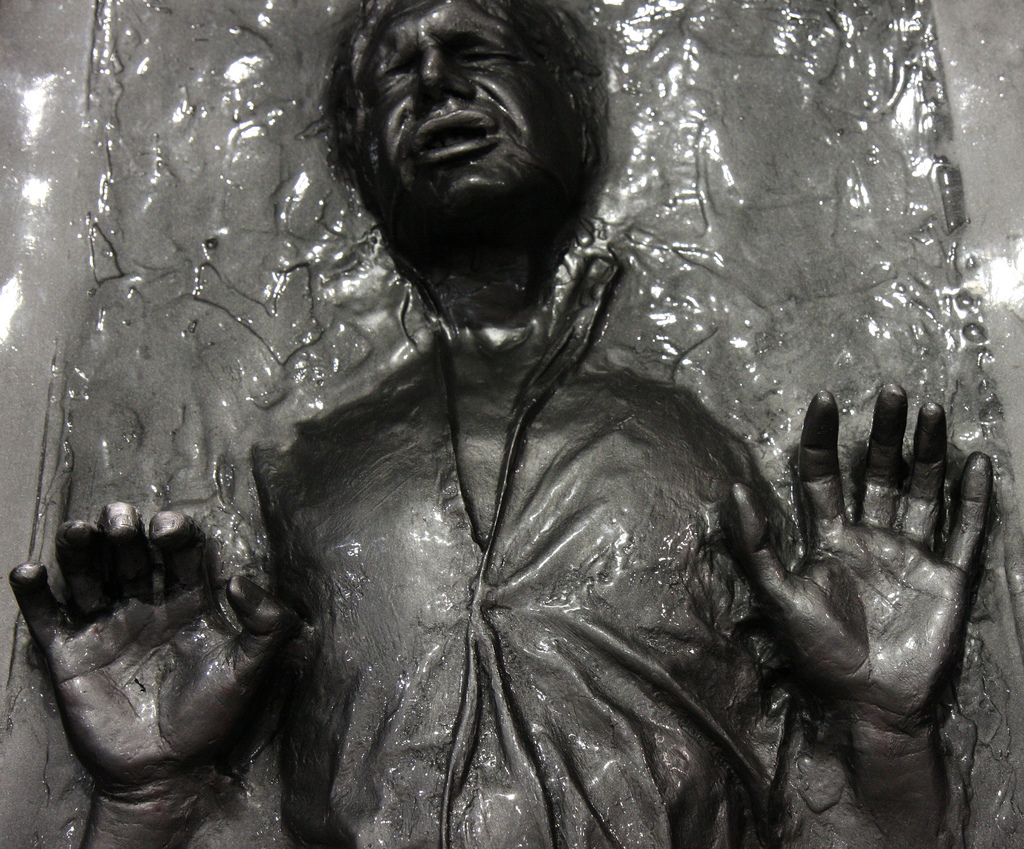

Suspended animation has been a staple of the science fiction genre for generations, appearing in everything from The X-Files to Star Wars — but now it’s set to become a reality. According to New Scientist, the first human trials will begin at the UPMC Presbyterian Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania later this month.

The trial patients will be victims of severe traumatic injuries such as gunshots and knife wounds. Once their heartbeats and brain activity have ceased and they are unresponsive to resuscitation, their blood will be drained and replaced with a chilled saline solution pumped straight into the aorta, rapidly cooling their bodies from the normal 37°C to only 10°C. This will result in a state of suspended animation that can last for several hours — although the medical professionals testing out this new method aren’t comfortable calling it that.

“We are suspending life, but we don’t like to call it suspended animation because it sounds like science fiction,” Dr. Samuel Tisherman, who is leading the trials, told New Scientist. “So we call it emergency preservation and resuscitation [EPR].”

By putting the patients’ bodies into a profound state of hypothermia while they’re on the brink of death, surgeons will buy precious extra hours to operate on their injuries. Although brain damage due to oxygen starvation is a serious danger when stopping the heart at regular body temperatures, it’s not a risk at lower temperatures due to the body’s chemical reactions being slowed down, which causes the cells to need less oxygen. After the procedure, blood will be pumped back into the patients’ bodies and their hearts will be restarted.

Dr. Peter Rhee first tested the EPR technique in 2000 on pigs, first anaesthetizing them, then inflicting arterial damage designed to mimic deadly injuries from car accidents or gunshots. Among the experimental group that underwent the EPR procedure, Rhee reported a 90 per cent success rate. The animals were revived without any apparent cognitive or physical damage once their warm blood was replaced, despite being clinically dead for several hours. Of the control group of pigs which did not undergo the procedure, none survived.

Because the potential EPR patients will be suffering from deadly wounds that require rapid intervention and will likely be unable to give consent, the FDA has permitted Tisherman’s team to perform the EPR procedure without their patients’ approval. The team has offered the public the ability to opt out by signing up on their website, but so far no one has chosen to do so.

The results of the human trials will be measured against a control group of similarly injured patients in order to determine the procedure’s success rate, leading to future research and experimentation.

What does this mean for the medical community? If Tisherman’s trials are successful, it will revolutionize the field of trauma surgery, saving countless lives. With some development, it may offer a way to suspend incurably ill people until medicine catches up with their illnesses. If science fiction continues to inspire reality, perhaps it could even open the door to long-term space travel. At the very least, EPR challenges the current medical definition of death.

“After we did those experiments [on pigs], the definition of ‘dead’ changed,” Rhee told New Scientist. “Every day at work I declare people dead. They have no signs of life, no heartbeat, no brain activity. I sign a piece of paper knowing in my heart that they are not actually dead. I could, right then and there, suspend them. But I have to put them in a body bag. It’s frustrating to know there’s a solution.”