Print Edition: November 20, 2013

There’s a space storm that’s been raging for centuries – and until now, no one has been able to explain why.

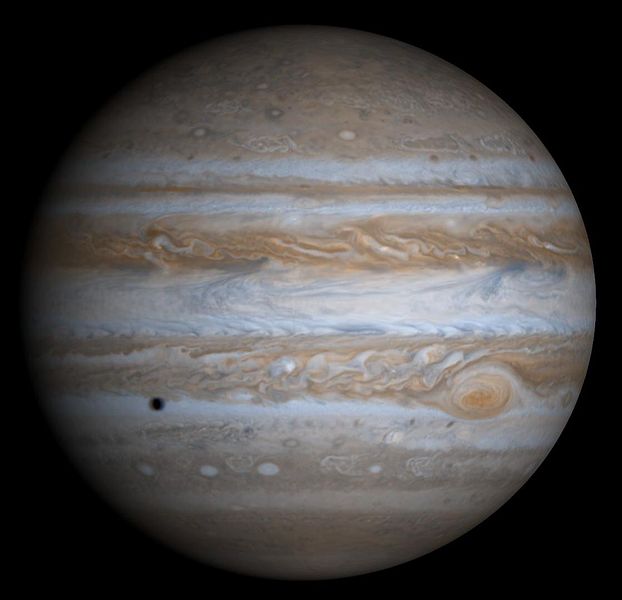

Jupiter’s red spot is perhaps its most recognizable feature – a pleasant visual break when viewed from space, but also a giant whirling storm in the planet’s atmosphere. Known officially as the Great Red Spot, this storm is approximately the size of three Earths and was boiling before humanity discovered fire.

Jupiter has twelve jet streams flowing in alternating directions, which are what cause the striped appearance of its surface. The Great Red Spot shoulders out space for itself between two of these bands. These two bordering streams should resist and slow the spot’s winds, and according to current theories the spot should also lose energy by radiating heat – the Great Red Spot is colder than earth’s polar regions, but is still slightly warmer than its surroundings. Among others, these factors point to the fact that the Great Red Spot should have worn itself out centuries ago.

Now two researchers think they know why the vortex appears to have no intentions of settling down.

“Based on current theories, the Great Red Spot should have disappeared after several decades. Instead, it has been there for hundreds of years,” Dr. Pedram Hassanzadeh, a post-doctoral research fellow at Harvard, told Science Daily last week.

He and his partner, fluid dynamics professor at Berkeley Dr. Philip Marcus, built a high-resolution three-dimensional model of the spot, capturing not only the horizontal winds of the vortex but the vertical flows as well.

“In the past, researchers either ignored the vertical flow because they thought it was not important, or they used simpler equations because it was so difficult to model,” Hassanzadeh told Science Daily.

Most of the energy being thrown around in the Great Red Spot is travelling in the horizontal winds, but Hassanzadeh and Marcus found that the vertical flow brings hot and cold gases into the centre of the vortex from above and below, replacing the energy the horizontal winds constantly lose.

The researchers also found their model hypothesized that a radial flow runs around the edges of the spot, sucking in power from neighboring jet streams and fueling the vortex.

Hassanzadeh and Marcus are preparing to present their work at the American Physical Society’s Division of Fluid Dynamics later this month. The research they’ve done into the Great Red Spot may also apply a little closer to home – some underwater oceanic vortices, for example, operate on the same principles of fluid dynamics. While they might not have the same lifetime as Jupiter’s spot, they sometimes can last for years at a time.

For now, Hassanzedeh and Marcus are modifying their model to include an older theory, which suggests that once in a while the Great Red Spot sucks in smaller vortexes and feeds on their energy to power itself.

“Some computer models show that large vortices would live longer if they merge with smaller vortices, but this does not happen often enough to explain the Red Spot’s longevity,” Marcus told Science Daily.

But working that into the fluid model might just be one more piece of the Great Red Spot puzzle.