By Katie Stobbart (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: March 25, 2015

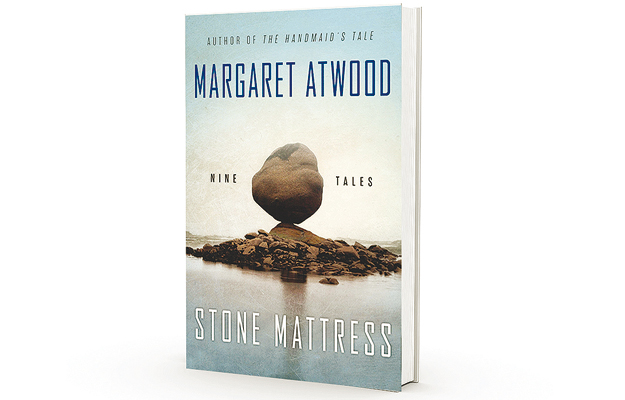

“It’s astonishing how folks can get so worked up over something that doesn’t exist,” muses Constance, the author of an imaginary world, “Alphinland.” The first three stories in Margaret Atwood’s Stone Mattress are linked to Constance and the world she writes into a successful, if notably non-literary, fantasy series.

Alphinland is not a real place.

That is not exactly a true statement. Despite its status as imaginary, Alphinland is real in its threat to a poet’s ideas of what real literature is; insofar as it sculpts the research focus of a young scholar; and in the myriad ways it affects or is affected by “real” characters (within the larger context of Atwood’s made-up story).

Such play with the layering of realities continues throughout the book.

With three linked stories out of the starting gate, one might expect the following six to carry forward a short story cycle. However, neither Alphinland nor the characters from the first third of Stone Mattress reappear in later tales.

Any budding expectations of how the stories might cohere are interrupted by “Lusus Naturae” (“freak of nature”). Though the story’s first-person narrative purports a kind of realism, the fact that it is told by a quasi-mythic heroine-or-monster calls its likelihood into question. Its authenticity, though, depends less on an argument of whether or not such events could happen and more on the way Atwood shifts the lens. I’m reminded of “Half-hanged Mary” and “Owl Burning” in morning in the burned house. The maligned character — the witch, the monster transformed beyond popular recognition of humanity — is no less human, having faced the darkness, looking back with mirror eyes.

By this point in the collection a unifying element begins to show itself: our love of scapegoats, of using human figures as figureheads when blame is to be laid.

“When demons are required someone will always be found to supply the part, and whether you step forward or are pushed is all the same in the end,” Atwood writes in the freak of nature’s voice.

The stories that follow darken gradually, and are eerily plausible. Maybe at first you are astonished when a group of radicals blockades and burns down retirement homes, but it becomes believable and unnerving when you realize you’ve heard this narrative before somewhere: in the news, maybe. It’s a strange, hard bed to lie in.

In many ways, Stone Mattress is unsettling in its portrayal of the modern world, using the same, perhaps more honest, way a long history of folk tales have depicted, somewhat askew, their respective contexts.

Maybe in another light (here, that of tales) the looking glass is clearer.

It’s also worth noting that despite their darknesses, most of these stories end with a strange sort of optimism: with love, with liberating calm, and dancing in the firelight.