I was sitting in the back of a 1974 Dodge Tradesman. My right boot, kicked up onto the counter to stop dinner from sliding off — terrifying right-hand turns. My left boot, braced against the stove to stop myself from bailing — lefts, too. Coastal roads are windy. In the event of a rollover, pillows would be deployed; and so would everything else from the overhead shelves and bed. Moving, rattling, bouncing — riding along while driving along the coast, flying like a bat out of hell. In my mind, I was still.

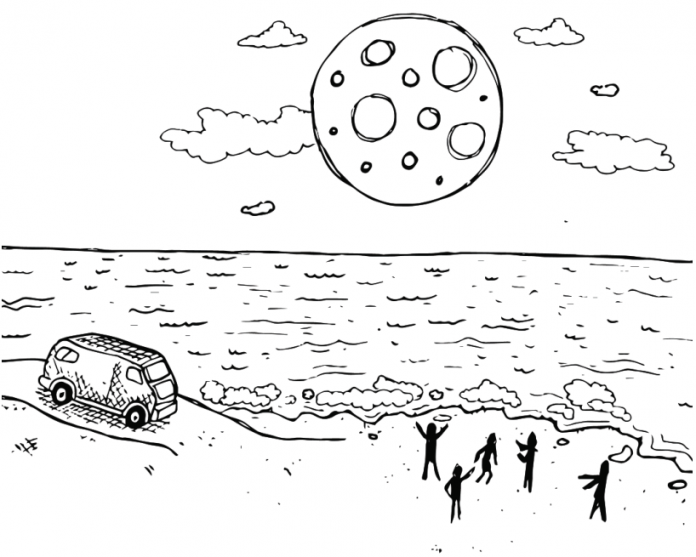

It was two days after the full moon. The moon, still bright, with just a soft shading on its left cheek. Three friends and I took off to rethink Thanksgiving — to rethink in general. We set a course for the shores shared by Discovery and Resolution.

We hit the beach by sundown and nearly collided with the moon. Beside us, a short row of old RVs and Subarus outfitted with roof racks, surfboards, and Aztec blankets encroached the rocky shoreline. Within moments of arrival, I wandered towards the waning tide.

Here in the Botanical Beach tide pools, near Port Renfrew, the sea does its best to recreate the night sky. It’s what John Steinbeck meant, I think, when he wrote, “It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool,” in The Log from the Sea of Cortez. When you stand over a tide pool at night, you stand over the sky — perspective.

My friends met me in the dark, on the edge of the ocean. We talked about the moon and the sky and the waves. We walked around the pools teeming with life. Red sea urchins, green shore crabs, and pink-tipped anemones populated the pools. Their dance is truly with the stars. Everywhere under the moonlight, something to discover or uncover.

Then, I was lost. Purpose pales in comparison to the grand plans of the ocean — cycles.

I realized: oh, here I am, “bound by the elastic string of time,” as Steinbeck put it. Getting lost in the double mirror reflection in the tide pool and everything it sends back at the night sky. Lost between the sea and sky. The beauty is undeniable, and it’s in what’s unknowable. I guess I’m okay with that. Somehow, we fit in as a part of it, anyhow.

When you stand over a tide pool at night, “the meaningless words of science and philosophy are walls that topple before a bewildered little ‘why.’”

When standing over a tide pool at night, friends nearby — the silhouettes of inland douglas firs and cedars defining the intertidal zone on one end, and the ocean retreating and intruding on the other — don’t forget to stop everything and ask, “why?”