By Jennifer Colbourne (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: October 16, 2013

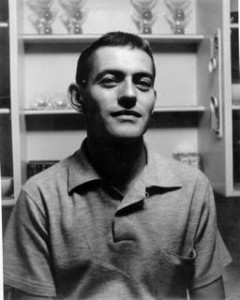

Miriam Nichols has been an English professor at UFV since 1994, specializing primarily in 20th century literature and literary criticism. Recently, she published a book entitled Radical Affections: Essays on the Poetics of Outside, and she is currently on sabbatical writing the biography of Berkeley-Vancouver poet Robin Blaser.

Nichols edited Blaser’s collected poems, The Holy Forest, his collected essays, The Fire, and has another of his works, The Astonishment Tapes, in the midst of publication. Now, this November, Nichols is heading to the UK to talk about Robin Blaser and 20th century poetics.

You’re lecturing at East Anglia University in Norwich and the University of Kent in Kent, correct? What are your lecture dates?

I am attending a one-day conference at East Anglia on November 23. This event is about the Vancouver Poetry Conference (VPC) of 1963, a rather famous event that brought a lot of American poets to UBC for lectures, workshops, and readings. The participants of that conference became very well-known. Among the Americans were Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, and Denise Levertov, all of them rock stars of the mid-20th century literary avant-garde; the Canadians were student-poets at the time, but they too developed luminous writing lives – George Bowering, Fred Wah, Daphne Marlatt, and Frank Davey among them.

The East Anglia event is called Beyond the Border, and it is a retrospective look at the intellectual heritage of those poets and of events like the VPC. That 1963 conference is the most famous of its kind from that period, but it was one of many. UBC professor Warren Tallman and his wife Ellen brought the New American poets, as they were called, to Vancouver on numerous occasions, so that there was a real cross-border discourse going on.

The other event is scheduled for November 27, at Kent University. The English department at Kent has a series going for guest lecturers and I’m to be one of them. So it’s not a conference – just me and some Kent faculty and students.

What are your lectures about?

The East Anglia paper is about the poet Robin Blaser’s take on the Berkeley poetry scene of the 1950s. Blaser was a colleague of Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, and Charles Olson, and of that generation of New American poets, he was the one who actually immigrated to Vancouver. He taught at SFU from 1966 to 1986, when he took early retirement.

I have done a lot of work on Blaser and this paper is coming out of a series of Blaser audiotapes that I have edited for publication. Blaser called these taped talks about his life and work “Astonishments,” and a selected version of them will be published as The Astonishment Tapes. The University of Alabama Press is doing that, but … I don’t know when it will be coming out exactly. Presses move in their own mysterious ways.

My paper for East Anglia is called “The Astonishment Tapes: Robin Blaser on the Berkeley Scene.” The scene in question is the arts scene around the University of California at Berkeley in the late 1940s. Some commentators call that period the Berkeley Renaissance because there were so many new writers and artists with new ideas floating around. Many of them went on to become pretty well-known, but they were students at that time. Blaser did his undergraduate work there between 1944 and 1949.

The Kent lecture is a little more general. It is called “Variable Measure in Modernist Poetry: Pound, Olson, Hejinian.” The term “measure” in the context of the paper refers not only to prosody [poetic form], but to aesthetic and social judgment – a worldview, in other words.

I am comparing three generations of 20th century writers from early modern [Ezra Pound], mid-century [Charles Olson], and contemporary [Lyn Hejinian]. In my view, these poets constitute a particular line or genealogy in avant-garde poetics, and my purpose is to track changes in that line over the three generations.

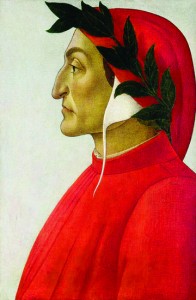

I think these poets are important because they try to do for the 20th century what some of the great epic writers did for the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Consider, for instance Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, the great Catholic epic of the 14th century. Dante gives us a journey through hell, purgatory, and heaven, and the cosmos that comes out of that journey gives shape and meaning to historical person and events. That’s what poetry is about – making meaning rather than creating knowledge in the scientific sense. Or consider John Milton, the poet of Paradise Lost, who again re-wrote the universe, this time from a Puritan perspective.

We don’t see the writers of our own times in the same way, perhaps because they are too close to us, but Pound, Olson, and Hejinian, after their fashions and from a secular perspective, give us the world again.

Tell me about your sabbatical project.

My sabbatical project is a literary biography of Robin Blaser. It will be called Performing the Real: A Biography of Robin Blaser. A literary biography considers the work, as well as the life, of its subject, so I am writing about Blaser’s development as a poet and the significance of his work as well as the details of his life.

This project is closely related to the UK papers. The talk at East Anglia on The Astonishment Tapes is directly relevant to the biography. The tapes are, after all, Blaser’s own account of his early life. They were never finished, but they contain some very important information. Blaser worked his way up to about 1955 (he was born in 1925), and then the energy for the series just ran out.

To contextualize a little more: these talks were recorded at the home of Warren Tallman [the above-mentioned UBC professor] in front of a small group of Vancouver writers. There were tensions between Tallman and Blaser from the beginning, and some of them were over what biography is supposed to be. This was one reason why the series was never finished. Blaser always considered his writing life an integral part of his biography, and by writing life I mean his journey in language as a poet – the intellectual moves he was able to make and the battles he fought with his peers over poetry. Tallman was more interested in biography in the conventional sense as the personal story of a life. There is a lot of push-pull on the tapes over the direction of the talks.

The talk on modernism at Kent is related to the biography at the level of ideas. I’m not talking about Blaser, but I’m talking about a genealogy of poetic art that he spent his life thinking about and contributing to. I’m sure it seems quaint to talk about poetry now because it is such a marginalized genre, but think about it as the engine under the hood of the literary car. Most people want to know how fast the car goes and whether it looks cool. But the engine makes it go. Poets are technicians of the literary imagination. To shift metaphors, Shelley said that they are the unacknowledged legislators of the world; Charles Bernstein said that they are the legislators of the unacknowledged world.

How did these opportunities come about?

The contemporary poetry world is pretty small. I heard about the East Anglia event through a friend who is doing graduate work on contemporary poets at the State University of New York at Buffalo and just sent in a paper proposal. (And by the way for your readers, SUNY Buffalo has one of the most comprehensive poetics departments among US universities).

I didn’t want to cross the pond just for one conference, however, so I contacted a friend at Kent to ask if there was anything else going on in poetics at that time.

Are you excited to go on your trip? What else do you plan to do in England?

Well, I have some days in London between East Anglia and Kent. If I can get it set up, I would like to interview Sir Harrison Birtwistle for the biography. Sir Harrison is a composer and he worked with Blaser on The Last Supper, an opera about the titular biblical event that focuses on an imagined conversation between Christ and his disciples. What would Christ say about the history of Christianity if he and the disciples were to reconvene in the year 2000?

Blaser wrote the libretto, Birtwistle the music, and the opera was debuted in Berlin in 2000. That libretto was Blaser’s last sustained work, although he wrote a lot of short lyrics afterwards. Blaser died in 2009, but he was ill with a brain tumor some years before that. I’m hoping to talk to Sir Harrison about the process of writing the opera and about his impressions of Blaser.

Do you think it’s important to lecture abroad/bring in guest lecturers to universities?

It’s important to keep up, however one manages that. I love the exchange with colleagues and students. I find that very stimulating. Sometimes that exchange can really shift one’s point of view and I look for those occasions. Keep moving, keep thinking, get better. There’s a phrase by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze that I love—the clear zone—expand your clear zone – that’s the point. I need a T-shirt with that phrase on it.

I suspect that many students, if you asked them to come and be lectured to (especially about poetry), would run screaming, but such events can be transformative. I had a wonderful experience with some Berkeley students this past spring. They pushed me hard with their questions, I can tell you, and I’m always grateful for that. Universities have as a mandate the exchange of ideas, and guests can contribute mightily to that aim.

Events don’t have to be faculty-driven either. The whole Vancouver Poetry Conference thing that has gone down in literary history as such a big deal was very much student driven. Tallman had a class on what was then contemporary poetry – we would probably call it postmodernism. It was awfully hard stuff and the students had lots of questions, so they put their money together and paid Robert Duncan’s travel expenses from Berkeley to Vancouver. They wanted him to explain his difficult poetry. The 1963 VPC came after that event. So who would you like to see? You never know – it might be possible.