By Paul Esau (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: March 20, 2013

I don’t know when I first held a basketball.

I was probably two or three and there’s probably a photo of it in an album somewhere. Most likely it was Christmas, since my dad spent the first decade of marriage with the word “basketball” at the top of his Christmas list.

It didn’t matter how many basketballs he got, that word stayed at the top, not that we could afford decent basketballs in those early years.

When I was seven or eight we bought a portable hoop from a neighbour and set it up at the top of our driveway. It sits there to this day, staring down the 20 per cent grade to the street below. We used to joke we had our own ball machine, since every rebound would roll right back down the driveway.

I’ve spent a lot of time staring at that hoop, shooting on that hoop, cursing that hoop. When I think about my basketball-playing days, I think of that hoop, of the hundreds of games of “Around The World” I’ve played on that hoop.

And the man I played against.

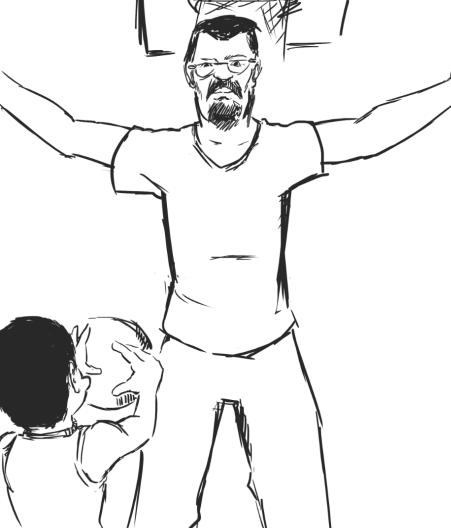

My father didn’t just collect basketballs every Christmas, he was the sport’s physical incarnation in our house. He was the one who signed me up for all the Friday night leagues and the summer camps, the one who, when I wanted to go inside, would say “20 more shots.” Becoming a true basketball player, for me, was supposed to be the moment I could beat my father one-on-one (in a game to 11, possession after three). That was the true rite of manhood.

Honestly, I can’t remember if I ever did beat him. At some indeterminable point I realized that I did not love basketball the way my father did, and I turned in a different direction. I played him occasionally after that, but never aggressively, never the way real father-son competition is meant to be played.

I know that hurt him. He loved the game and he wanted me to love it the same way. He could tell childhood stories of practicing outside in sub-zero Albertan temperatures, forced to adapt his shot to compensate for gloves. He sacrificed for the game; I sacrificed the game for my other dreams.

I always thought that at some future point I might get back into basketball, perhaps join a men’s league, and finally return to the gym with my father. It was on the agenda somewhere between a day-dream and my “five-year plan.” I figured I could always return to form, using the maturity of a 20-something academic to compensate for the burgeoning athleticism of a high-school senior.

What I didn’t realize was that my father’s time had run out.

No son really understands the effects of time until they compare the image of the father of their youth to the one before them as a young-adult. I remember my father as the white Albertan beating upstart players from the college team, the man with stories of playing street ball in the Fresno ghetto.

Then I blinked, somewhere between 19 and 22, and life, as it often does, changed the rules.

I can’t remember the last time my father played basketball. I should know, he always retells his defeats and triumphs over dinner on the days when he competes (in almost any sport). But sometime, a few years ago now, he simply stopped playing. It was only recently that he revealed why he’d had to quit.

I didn’t notice at first. In my mind basketball was too much a part of my father to be separated from him. Despite his age he had always worked harder, competed harder, been more intense on the court than I cared to be. It shocks me, even now, to think he’ll never unwrap a Christmas basketball again, or get his photo taken on a court wearing those horrible pastel ‘80s shorts.

And it hurts me, as I know it hurts him, that I’ll never really be the player I could have been. I’ll never shake his hand after that final, eleventh basket, and look him in the eyes as the baton is passed to the next generation of Esau athletes. The chance to complete that rite of passage is gone for good.

I wish I’d realized it was slipping away.

Yet my father is not a man to give up on sport peacefully. Six months ago he drove to Vancouver to buy a squash racket, and returned with an ugly, stubby implement that made me laugh. “Why?” I said, “squash is a sport for sweaty old men!”

At that point he didn’t answer, he just looked at me, and I felt the uncomfortable premonitions of something I didn’t want to understand.

He plays squash almost every day now over at Apollo. Sometimes he wins. Sometimes he loses. Every time, I hear the scores over dinner.

Every once in a while I tag along and play this alien game that was not at all a part of my childhood. We used to play to 11 points, but then one day I got to 11 first and my father decided that, actually, we were playing to 15.

I’ve never reached 15 first.

And I hope I never do.