Mission: find a room.

But I keep getting distracted. The subway looks like a mirror held against a mirror — row after row of people stand and sit. They all look the same. The SkyTrain, which I’m familiar with, is made of seperate cars — can’t look the length of it. Looking straight down the TTC Subway, passengers arc their way up — first the front, then each car follows — and to the side and down and around as the subterranean train winds beneath Toronto. The way it looks: like when you stare into a reflection of a mirror in a mirror, and move it around. It bends with each mirror after mirror, passenger after passanger, forever.

I’m looking at the other passengers, obviously disinterested in my affairs, but I’m ready with a defence for anyone who might ask. “I figured I’d have a better lay of the land once here,” or something. Second night in town, and still no room. Fortunately, a friend’s parents put me up for a night.

Spending time to spend less on a room, I’ve wasted hours since I landed, on and off, scrolling through Airbnbs. Now I just want something under $40 a night. The week between Christmas and the new year: should have booked a month ago. Hostels are good, practically the same price as a cheap hotel though.

Here I am, counting each cent for the night, and yet I’ll spend more on lunch than the night’s bed. The economy of being a millenial.

Let’s go with a hostel. Mine’s the next stop, I’ll book when I surface into reception. Not sure if I’m living out of a suitcase, proverbially, metaphorically speaking, or living out of an iPhone.

I trip up the stairs from the TTC subway: Daylight. Foreshadowing? I awake, essentially, to a bundle of filthy blankets and Tim Hortons cups.

“Cold?”

“Huh?”

“Are you cold?” I clarify. Probably too casual with someone I don’t know. It’s a habit.

“No,” he asserts.

The walk sign changes.

“Cool,” I respond. Great help I was, I think as I walk on with a mob of pedestrians. At least I asked. This isn’t the West Coast, you can’t just live outside here. How do they do it, I wonder.

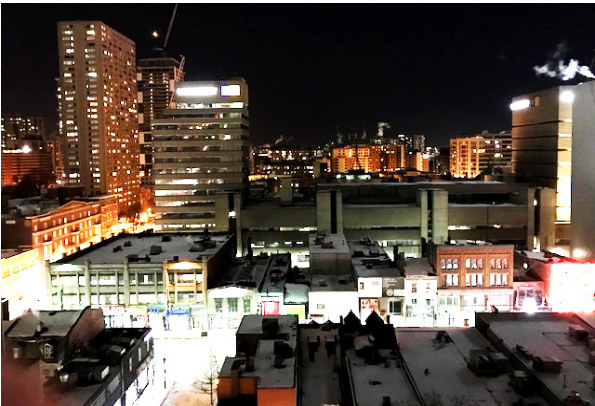

College and Yonge Street. From here, the sky looks bright and clear. The air is a lie though; everything I look at, concrete and glass walls, alleys, gigantic advertisement screens, it’s all on the other side of a -10°C choke hold. In minutes, my moustache is ice — condensation from breath. Not long after, the rest of my beard is stiff.

The hostel emailed a booking confirmation. That was easy. Dragging my carry on — ready to burst, with two weeks’ provisions — I walk south on Yonge. I could have checked a larger bag, but I will not lose another blazer at Toronto Pearson.

The city is complex. It’s also contained.

Getting to the hostel, I double check the address. Won’t make that mistake again. Steep stairs lead to a glass door, which opens to more stairs stretching out of sight. It’s all brick. The hostel patio is small, just enough room for a team huddle and an ashtray. Hostel door on the left, backdoor of a Mediterranean diner on the right. Not a bad pair.

I climb the flight and wander to the front desk. Apparently it’s overbooked, and someone’s sleeping on the couch. I get a bed by luck; I don’t inquire, it’s probably a mixup. Is it odd that the hostel’s patrons include businessmen and well-dressed travellers? Can nobody afford a real room, or is this slumming? Is it neither, is the hostel a cultural experience? Explains the rising prices.

“There’s a $10 deposit for a key. The outside door locks at 11:00, so I recommend getting one. I’ll get you your bed sheets. Bathroom’s before the kitchen. Take your shoes off at the door, too much water getting tracked in.”

“Cool, thanks.”

“Any info you need is on the board behind you, or ask. Wifi password’s there too.”

“Great.”

“The bunk at the back of the room is free.”

“The room at the end?”

“Yup.”

“This one?”

“Yes.”

“Thanks.”

I hoist myself up the bunk ladder, the whole bed leans into me. Instinctively, I lean into it, rebalancing. It steadies. Reassuring. Glad I’m on the top.

Unpacked, sheets mounted on the bed, laptop hidden: dinner sounds good. Where to go? I start out.

You can feel the ice in the air. A chill that seems mythical, so I’d been calling it a dastardly wind.

I first stroll, then canter, keeping pace with determined looking walkers. Determined to arrive, or determined to stay warm? Not sure where I’m going yet, I like a quick gait, though. Where for food? I don’t even know the town’s districts. There’s familiarity in Chinatown: unfamiliarity. Foreign characters, unreadable languages. Just like the cities I know well. Just like home.

Walking south, I pass giant financial institutions, and their big buildings. A cathedral, large in stature, but not looming. Just ornamental. I wonder what they do inside. St. Andrew’s, it says on a sign. I had guessed St. Peter’s.

Along the way, I notice every manhole is hidden by a body, curled up, collecting heat from the escaping steam. Rancid smell, I wonder how long it takes to get used to. Through an alley, behind a hotel/bar, then down towards the CN Tower, I wandered too far; got to go west, and back north a bit. Now late for dinner. Late for a date with my imagination.

Back to the hostel. Home for the week. Abode for deployment — to galleries, museums, and jazz bars — basecamp of the adventure. That’s what the city’s good for. It has to be good at it. A good city is a mosaic. This is the melting point, boiled down to a cultural reduction.

Sunday.

My phone’s second morning alarm increases in volume, and I flail through the sheets to find it. Adrenaline now deployed, I kill the soft piano music — which is actually awfully harsh piano music — anxiety inducing — as it gets louder and louder. Music off, the room realizes it’s calm once again. Someone rolls over; the sanitary plastic hospital-style mattress shrieks and crumples under any twitch. I prop myself up slowly, to avoid waking this banshee.

I figured I’d go to St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church — it’s more of a cathedral (technically Romanesque Revival) — for their Sunday morning service. A cultural experience, never been to a Presbyterian church. I also became curious about the sandwich board sign out front that I passed on my way to a pub. “Out of the Cold,” it said. Food program for homeless or something.

I put on what some of the hostel-mates call my “Vancouver jacket.” “Vancouver,” because it looks good, but that’s about all it does. Brown boots slipped on; scarf wrapped tight and tucked into my vest. Ready.

The cold is disorienting.

I arrive at St. Andrew’s: Wooden doors, large. A shivering doorman with a welcoming smile.

“Can I bring this inside?”

“I don’t see why not,” he responds, smiles knowingly.

I sit down, spend a moment balancing my coffee beside me on the wooden bench, give up, set it on the ground, and begin to take off my coat. No, better not; it’s cold inside too. I reverse the landing process and take a sip of coffee, this time keeping it in hand. I settle back as an observer.

The preacher’s sermon is themed on the new year, looking forward. We sing hymns older than this city. We stand up, sit down; stand up, sit down. Rituals.

He delivers parting words, and mentions the Out of the Cold program: “We can always use more hands. Plenty of potatoes, onions, and carrots to chop.”

Leaving the sanctuary, we shake the preacher’s hand: “Thank you, pastor. Great sermon.”

A priestly looking priest. A look that makes him hard to see. Hard to differentiate from past priests.

He extends his hand. So do I, then I pause.

“Do you actually need people, or was that a pleasantry?”

“No, no. I think today we’ll be short. We usually do need more hands.”

“I’ll stay then.”

“Wonderful. Follow the back hall. The ladies in the kitchen will put you to work.”

I turn and walk. “Thank you, pastor. Great sermon,” I hear over my shoulder.

I pass stained-glass windows set in the brick walls of a darkened room. They turn the sun’s light, pure light, into rainbows. The colours fall around my feet. They’re pretty. They’re beautifully crafted, but do a damned job at brightening the room.

The back of the cathedral is complex. There’s a language within the rite. Each sign and symbol, significant for some reason, whether for conveying divinity, sovereignty, or for the sake of itself — meaning lost to time, only the symbol remaining. A symbol of time, but only implied.

The back of the building, behind the sanctuary, is outfitted with a proper kitchen and tables set up in the adjacent room. A box of knives and boxes of vegetables on one table. I hang my coat with dozens of others at the entrance, roll up my sleeves, test the knives’ sharpness.

Chopping is meditative. Slicing, peeling, sorting; all forms of meditation. Great sages must have peeled a lot of potatoes, I think to myself. It’s true. Peel, peel, peel; chop, chop chop; knife down, cutting board up, slide the cubes into a bucket. I repeat several times before changing techniques. Peel, chop; peel, chop; peel, chop; knife down, board up, into a bucket. The first technique is faster, but I’m new to meditation, and monotony feels a lot like withdrawals.

Leaving, I’m encouraged. It’s good to be in a room of strangers prepping food for the hungry. Encouraging each other in love, as it were; love for a city.

I start walking home, walking as fast as is just short of a jog. The streets are chaotic and angry. It’s busy, very busy.

Home. Leaning on the stairwell of my hostel’s porch to chat with a few hostel mates on their cigarette break; I watch a car wait more than 10 minutes before inching into the torrent of pedestrians to push past into a left turn. Road traffic speaks, horns a conversation between frustrated drivers. There’s tension, aggravation. People walk quickly. It’s New Year’s Eve, and it’s still cold.

New Year’s is extravagant. Fireworks are nice. Fanfare and crows. The mates and I stay up late. Two minutes from the action, we walk back and forth from the Nathan Phillips Square, where the outdoor ice rink and fireworks are. Where the concert was supposed to be. It’s too cold, so the city shortened the lineup. It’s just too cold to be outside at night. We brave it for smokes and cheers, but our night needs the light and warmth of the indoors.

I awake, shower, pour coffee, stare at a plate of crackers and cheese, pour another coffee.

In the common room, there’s a TV. I switch on the CBC. First story of 2018: Another cold weather warning was issued last night, beds went unfilled.

Apparently there was “confusion” over the amount of free beds available to homeless. Several workers were told that the shelters were full. They weren’t.

It was -22°C, no confusion about that. Last night, most shelters operated at 94 per cent capacity. Street workers who called in looking for beds were told the shelters were full. The CBC story continues: city officials confirmed that the 62 shelters are at 94 per cent.

Doug Johnson Hatlem, activist and former street pastor who spent seven years advocating for the city’s homeless, called the central intake to ask if beds were available at the city’s newest emergency shelter. When he walked down to the shelter, it appeared that there was space. He accused the city of being cheap, said city staff deliberately “fudged” data.

Apparently independent shelters get paid a per diem for the beds that are filled, the CBC reported, not the beds that sit empty. If the bed’s unfilled, the city doesn’t have to pay for it. The city explained why the beds were unfilled: Paul Raftis, the general manager of the city’s Shelter, Support and Housing Administration (SSHA), told reporters that he’s “very concerned” with the communications mistake. He blames a “very dynamic” system, in which the beds “fill and become empty regularly through the 24-hour period.”

“They have beds, but they’re not releasing them,” Hatlem said, suggesting it wasn’t a miscommunication between Toronto’s shelters and the downtown call centre that’s exposing the city’s unhoused to the bitter cold.

“This is a strategy the city has had for years. Once they get over about 90 to 95 per cent capacity, then they start telling people the beds are full.”

“Damn.”

I pull up the Globe and Mail app on my phone. Pullquote: “Someone is not counting, or somebody is outright lying.” Said by Paul Ainslie, councillor for Scarborough East.

Interestingly, the community responded. The CBC story continues: Jennifer Evans, a community volunteer, saw that one of the intake centres posted that they were full. She reached out to her online network saying she’d pay for a hotel room if others did too. Over 130 people pledged to pay for rooms, some paid for multiple rooms.

Street workers, activists, and overdose prevention workers all reported over the course of the weekend that they couldn’t find beds.

A man isn’t far from street living. Three or four bad decisions away from sleeping on the ground.

Curiously, this hostel shuts down for good this week. Another hostel to close. More money in renting space to lawyers. The long-term tenants here will probably find another room. Probably. The unhoused on the streets of Toronto and Vancouver weren’t capable of civilized living — unique cases of falling from grace. Nothing like my situation.

I lay back on the common room couch and I wonder: what does it mean to be one of the richest cities in the world? Must be a complex issue.