By Alex Rake (Contributor) – Email

Print Edition: October 1, 2014

Leonard Cohen’s latest album, Popular Problems, never reaches the same dark, transcendental depths of his earlier records; there is no “So Long, Marianne,” “Dress Rehearsal Rag,” or “Hallelujah” here. But who says a Leonard Cohen album needs to bring you to your knees in order to rejuvenate your spirit, anyway? Popular Problems is a lovely example of how transcendence can point right back down to Earth.

As with 2012’s Old Ideas, the lyrics here are simple, and many of them are taken from Cohen’s sketch, meditation, and poetry collection The Book of Longing. Those who admire Cohen for the conceptually dense and often shocking lyrics of his earlier work may be turned off by the lack of outrageous imagery and the prevalence of basic couplets. In other words, instead of visual, provocative lines like “Jesus was a sailor / When he walked upon the water / And spent a long time watching / From his lonely wooden tower” (“Suzanne” from Songs of Leonard Cohen), we are given abstract statements like “I could not kill the way you kill / I could not hate; I tried, I failed / You turned me in; at least, you tried / You side with them whom you despised” (“Nevermind”).

This trend towards the abstract is not a decline of poetic talent but a shifting of gears; Cohen’s lyrics used to attempt an understanding of the transcendent, taking the listener along for a bittersweet ride, while now they seem to meditate on whatever that achieved understanding, so far, is. Cohen has become more secure with his place in existence, and so is (paradoxically) freer to do things with a calmness and simplicity that were previously impossible.

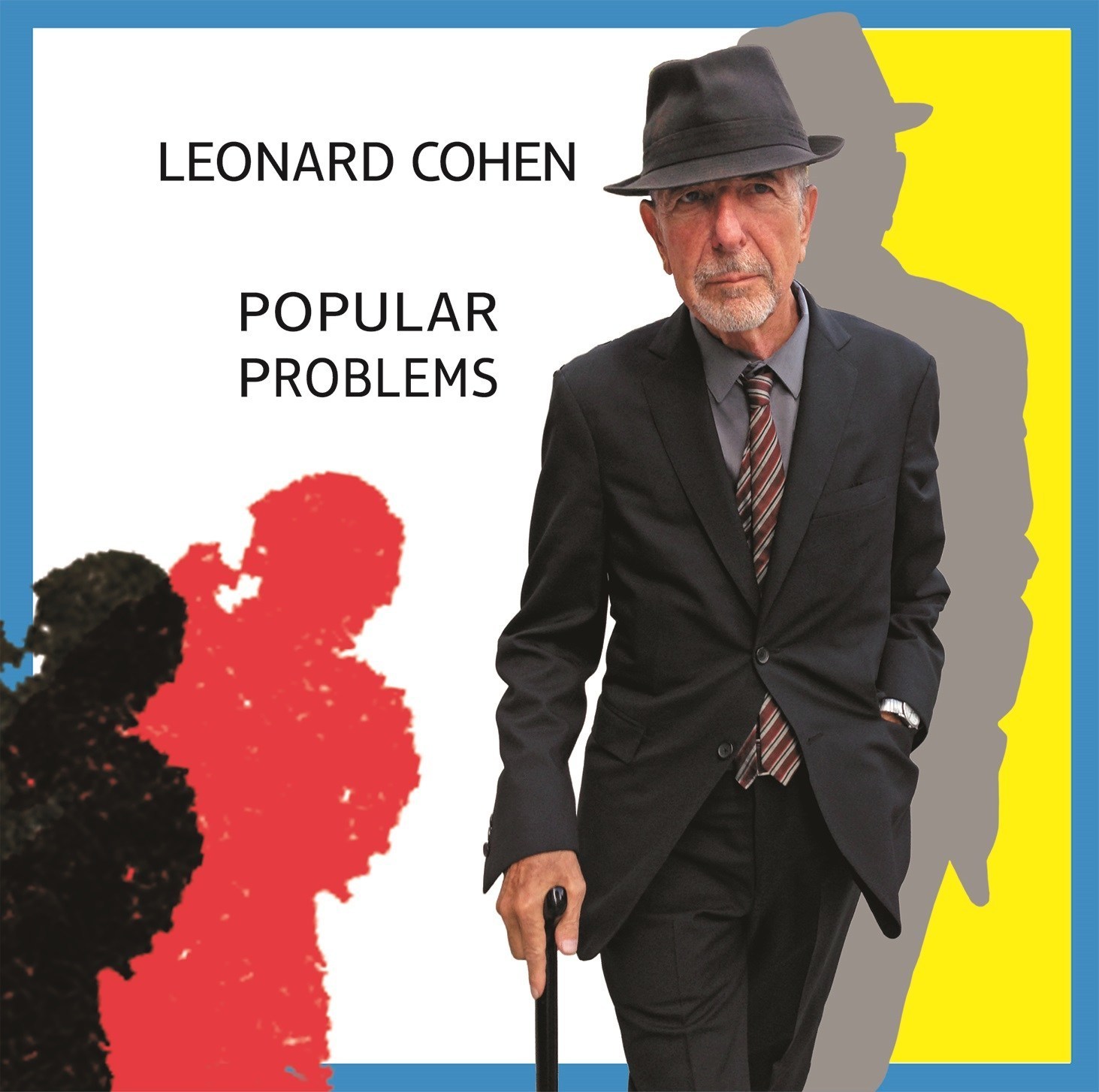

As an extension of this freedom, the compositions are especially playful. A look at the cover should give a preview of what the album sounds like: simple, flat, and incongruous. None of these are insults because Cohen’s producer, Patrick Leonard, did it right: choices like allowing the heavily-produced arrangements to have dynamics, having the cheesy belting-out of Cohen followed by the country-western beat and female chorus on “Did I Ever Love You,” and inserting the unexpected (but not unwelcome) Arabic back-up vocals on “Nevermind” contribute to the album’s refreshingly playful feel.

Even serious moments like “Born in Chains” don’t dominate the fun that threads through the record. The delightful “You Got Me Singing” follows the deeply spiritual “Born in Chains” and ends the album; instead of leaving us with a prayer, Cohen gives us a sweet little love song: “You got me singing even though the world is gone / You got me thinking I’d like to carry on.”

The simplicity and playfulness of the album do not suggest that Leonard Cohen is a spent old sack of songs; rather, these aspects reflect the spirit of a poet who has trudged through the gutters of experience to discover he is alive, on Earth, after all.