By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Date Posted: October 20, 2011

Print Edition: October 19, 2011

Somewhere Between (USA)

Put a crying girl in front of a camera, and it’s clear what will happen to the audience. When this happens in a documentary interview, the reaction ideally should not be to mimic the onscreen visuals, but to question what kind of questions were asked to lead to such a reaction, and what the purpose of the questioning is. Somewhere Between opens with director Linda Goldstein Knowlton onscreen, receiving an adopted Chinese baby girl in slow motion, with orchestral music filling in those who are a little slow in gathering just how important an event this is. This documentary, apparently, is for that baby girl. While the idea of trying to be the best mom ever by figuring everything out for a child before they need to is inherently parental, the question is what the point is from the point of view of the audience.

Put a crying girl in front of a camera, and it’s clear what will happen to the audience. When this happens in a documentary interview, the reaction ideally should not be to mimic the onscreen visuals, but to question what kind of questions were asked to lead to such a reaction, and what the purpose of the questioning is. Somewhere Between opens with director Linda Goldstein Knowlton onscreen, receiving an adopted Chinese baby girl in slow motion, with orchestral music filling in those who are a little slow in gathering just how important an event this is. This documentary, apparently, is for that baby girl. While the idea of trying to be the best mom ever by figuring everything out for a child before they need to is inherently parental, the question is what the point is from the point of view of the audience.

Somewhere Between jumps between different adopted Chinese girls in different corners of the US, asking the same, stilted questions about just how difficult growing up is in a community not your own, how they feel about this and that etc., but never establishes much of a purpose. Perhaps to fill out its running time, the film segues into tourism advertisement as the girls fly to various corners of the planet to meet and greet, and hopefully find answers. Yet it is in these far away places the film finds some of its most hard hitting moments. It is not the tears, but the answers they arise out of in a questionnaire in Barcelona, that are affecting; the editing together with a separate tearstained interview is blatant audience manipulation, though. Same goes for the wordless reactions of a father in China. Somewhere Between’s best parts are when the director isn’t doing the questioning, when the confines of finding something unfindable are not placed upon its interview subjects, and when sappy music isn’t inserted into scenes. But again, there is very little eagerness to find the unexpected, the uninvestigated in this documentary. The girls’ stories are touching, but to what end are they divulging their secret thoughts? To prove that growing up is hard is to state the obvious. A direction less trite and ignorant than the idea of educational video diaries for a daughter might have yielded something with a better sense of purpose, and a better reason for the girls of Somewhere Between to spill their hearts out on a movie screen.

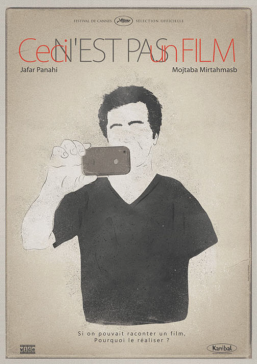

This Is Not a Film (Iran)

Jafar Panahi has made some of the best films of the past decade, not just from Iran, but anywhere. His films take the normal cruelties of life and turn them into narrative poetry, often dealing with relevant, contentious subject matter, yet abstaining from politics or blatant persuasion. Left in his house awaiting a verdict based on an initial sentence of six years in prison, 20 years banned from making movies because of the heated topics his films are about, Panahi does the unthinkable and treats his own situation with the same astounding level of reality and creativity in This Is Not a Film.

Jafar Panahi has made some of the best films of the past decade, not just from Iran, but anywhere. His films take the normal cruelties of life and turn them into narrative poetry, often dealing with relevant, contentious subject matter, yet abstaining from politics or blatant persuasion. Left in his house awaiting a verdict based on an initial sentence of six years in prison, 20 years banned from making movies because of the heated topics his films are about, Panahi does the unthinkable and treats his own situation with the same astounding level of reality and creativity in This Is Not a Film.

Made up entirely of documentary footage, it has the spontaneous, true-to-life feel of Panahi’s films; yet for every minute of watching it comes the dreaded realization that every minute actually occurred, that these are the last minutes of Panahi we might see for two decades. It gives the picture an added importance. These seconds matter, and in them we see Panahi struggle with this question of what filmmaking really means, what this not-film’s making could mean. The brilliance of Panahi comes through in how he does not make this the point, central theme, or answer to a burning question in This Is Not a Film, it just happens. Struggling to express himself in words, Panahi turns to films to explain his own situation, but in part also opens up the idea of cinema as higher communication, as something that can explain what we cannot in limited language. That he does so in an unplanned instance is proof that a world of cinema without Jafar Panahi making films is a lesser one.

“I think the main thing is to document” is said at one point. In documenting and editing this time in his life, Panahi not only captures the little bits of everyday life that are completely real and devastating to watch, but also the humour, the joy that can be found in bleak surroundings. (Despite the depressing reason for its making, it’s far from bleak.) Shot partly by iPhone, This Is Not a Film better exemplifies the idea that film can be created by anyone, in any situation, than any other digital experiment by a director. Not very many could turn it into as eye-opening a work as Panahi, but as the credits roll, we are left with the fact that he won’t be able to anymore, and for whomever wishes to, the tools and resources are there. A film that works as so many disparate yet here connected things: deconstruction of film, a final love letter to cinema, a documentation of a day, This Is Not a Film is everything movie-making should strive to be.

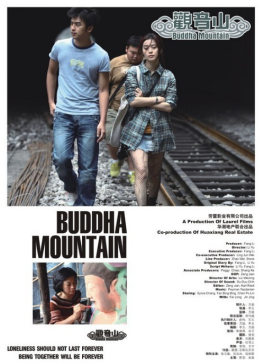

Buddha Mountain (China)

Buddha Mountain has no right working as well as it does. Its three principle roguish characters provide the film’s perspective: inane humour, (about a third of the movie’s lines, it seems, begin with “Fatso”) physical comedy that seems to swing hardest when it misses, and perhaps worst of all, a disconnect that plagues their interactions with their landlady, chief among them. Why this is so critical is that for all of the humour, both good and bad, what sets Buddha Mountain apart from the typical is the performance of Sylvia Chang as the woman renting out part of her home, from scene-to-scene both amusing and emotional, supplying the right amount to keep the movie afloat. But we’re stuck with the young adult view of boredom. Their unfeeling is off-putting, particularly in the cases of the older woman’s love of music and melancholy periods as a result of tragic loss.

Buddha Mountain has no right working as well as it does. Its three principle roguish characters provide the film’s perspective: inane humour, (about a third of the movie’s lines, it seems, begin with “Fatso”) physical comedy that seems to swing hardest when it misses, and perhaps worst of all, a disconnect that plagues their interactions with their landlady, chief among them. Why this is so critical is that for all of the humour, both good and bad, what sets Buddha Mountain apart from the typical is the performance of Sylvia Chang as the woman renting out part of her home, from scene-to-scene both amusing and emotional, supplying the right amount to keep the movie afloat. But we’re stuck with the young adult view of boredom. Their unfeeling is off-putting, particularly in the cases of the older woman’s love of music and melancholy periods as a result of tragic loss.

And then something changes. On their trip to the titular destination in a train, the words cut out and the music takes over. Now, hair flying in the pounding wind while driving, contemplative music that plays is little more than decoration, but it also represents a turning point in the movie. The focus shifts from clubs, pop culture and fat jokes to the protagonist’s difficult position in life, Chang’s character’s own difficulties, and culminates in two scenes that sweep away memories of the brash, teenage pandering opening. Familial tension, questions of satisfaction, and of grief, are hardly uncommon in film, but whether it’s the lowering of expectations from the first half, or that the first half consciously drew these characters as archetypes waiting to be broken, the later scenes work. Buddha Mountain remains a movie with flaws throughout, in its often jerky editing, and complete lack of grace moving between comedy and drama, but Chang adds enough to the movie that by its ending (which also could have been improved) the main impression is a positive one.

Alps (Greece)

If you take away the bonds of friends and family, the love of sports and movies, work and education, people are pathetic imitators of imitators, desperate, cloying creatures. Now laugh. That is the outlook of Alps, which adorns its drab frames with these types of characters, in an attempt to say the above about life, art, or perhaps nothing. Much of the attention paid to Alps around its release has been its insular, cryptic divulging of little concerning plot or explanations for why people do the things they do, but that is mostly dressing for what is at its heart an unoriginal statement.

If you take away the bonds of friends and family, the love of sports and movies, work and education, people are pathetic imitators of imitators, desperate, cloying creatures. Now laugh. That is the outlook of Alps, which adorns its drab frames with these types of characters, in an attempt to say the above about life, art, or perhaps nothing. Much of the attention paid to Alps around its release has been its insular, cryptic divulging of little concerning plot or explanations for why people do the things they do, but that is mostly dressing for what is at its heart an unoriginal statement.

If there was more than this philosophy to Alps, there might be something worth looking for, but the main twist director/writer Giorgos Lanthimos applies to his otherwise monotone movie is smatterings of sadistic humour. The sheer blackness of deadpan non-sequitur questions without punch lines is initially amusing, but is the only trick Alps has. Its mashing of the quotidian and the psychotic is so one note as to prove tiresome by its laborious ending for its protagonist. Perhaps to make a statement about the transience of identity, the most interesting characters in Alps are just about everyone but the one the movie devotes most of its running time to, but this accomplishes little that hasn’t been done before, and better. Antonioni was able to make alienation more than a feeling attributed to an onscreen character, and Herzog’s My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? as a recent example is a far more accomplished, harrowing and humourous look at life imitating artifice. Lanthimos can lay claim to quirky tales of inhuman depravity if he wants, but Alps exists in a niche that’s not nearly as excoriating as it thinks it is. It’s merely wretched.

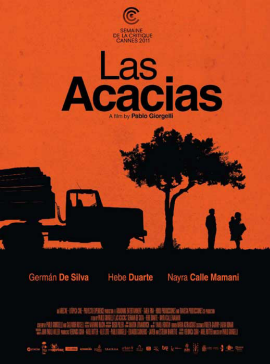

Las acacias (Spain, Argentina)

In Las acacias, a truck driver drives a woman across a border. Their journey unfolds in nothing but the grind of gears, rattling of windows, crunch of tires over dirt roads, and the silence between them. The suffocating normalcy of the affair draws the audience in, every eye droop, turn of the head, every word spoken (all 10 of them or so in the first half of the movie) is paid careful attention to. Like but not equal to the painful unrequited love of the films of Wong Kar-Wai, this first segment of the movie is obsessed with the minute. The camera refuses to move from its resting place inside the truck cabin. Lead actor German de Silva recedes so far into his role that it’s difficult to notice when the acting begins. There are more blinks than syllables in this movie, which makes one wonder what this style will lead to.

In Las acacias, a truck driver drives a woman across a border. Their journey unfolds in nothing but the grind of gears, rattling of windows, crunch of tires over dirt roads, and the silence between them. The suffocating normalcy of the affair draws the audience in, every eye droop, turn of the head, every word spoken (all 10 of them or so in the first half of the movie) is paid careful attention to. Like but not equal to the painful unrequited love of the films of Wong Kar-Wai, this first segment of the movie is obsessed with the minute. The camera refuses to move from its resting place inside the truck cabin. Lead actor German de Silva recedes so far into his role that it’s difficult to notice when the acting begins. There are more blinks than syllables in this movie, which makes one wonder what this style will lead to.

But Las acacias eventually concedes, and moves forward with a substandard romance plot. The two give their accounts: he lost a wife, and she is without a husband, and guess what happens. Director Pablo Giorgelli, perhaps not trusting the film’s audience to have the patience to regard its dusty, unimaginative frames, also brings out a cute baby every so often to liven things up. While there’s something to be said for the incredible lengths the film goes to show just how lonely and tedious a job like truck driving is, art house affectations are the more apt description for what provides this film with its only point of interest. While a film’s elements are inseparable, at its core Las acacias has little to set it apart from typical commercial romance pabulum. Just less words and longer takes.

Jean-Luc Persecuted (France)

Coming off the dissatisfying application of silence in Las acacias and the insulting faux-documentary look of Empire North, Jean-Luc Persecuted was a revelation. Featuring no words outside of its title and a breathtaking vista of hills and mountains, this mid-length feature takes the sometimes deployed experiment of silence in modern film and utilizes it in a way that avoids coming across as anything but right for this movie, it isn’t merely a gimmick. The absence of words leads to a different kind of storytelling, not a lesser one, one occasionally plagued here by going overboard in the depiction of actions to ensure nothing is lost in translation, but one that, in its economy, allows for greater range of expression. Words cannot be relied upon. Emotions cannot be explained away.

Coming off the dissatisfying application of silence in Las acacias and the insulting faux-documentary look of Empire North, Jean-Luc Persecuted was a revelation. Featuring no words outside of its title and a breathtaking vista of hills and mountains, this mid-length feature takes the sometimes deployed experiment of silence in modern film and utilizes it in a way that avoids coming across as anything but right for this movie, it isn’t merely a gimmick. The absence of words leads to a different kind of storytelling, not a lesser one, one occasionally plagued here by going overboard in the depiction of actions to ensure nothing is lost in translation, but one that, in its economy, allows for greater range of expression. Words cannot be relied upon. Emotions cannot be explained away.

Director Emmanuel Laborie understands that silence is not a limitation, but an outlet through which images, faces and music can carry a film in an effective way, one that is convincingly portrayed here as having less pitfalls than a typical dialogue-driven production. The film would fall apart without a great performance, not in the normally accepted shouting, hysterical, serious acting style that is awarded, but one exemplified by lead actor Guillaume Delauney. Through his eyes and face, Delauney is able to convey every aspect of his character. He so capably plays the role of silence that he appears like an actor from the era when this style of acting was the norm, but there is no datedness to his role, or this movie. Picturesque high definition visuals and an evocative score place it quite clearly as a movie of today, just one that embraces a method of storytelling underused not because of its inexactness or inferiority, but because it is apparently so easy to forget how moving it can be. Jean-Luc Persecuted is an impressive reminder.

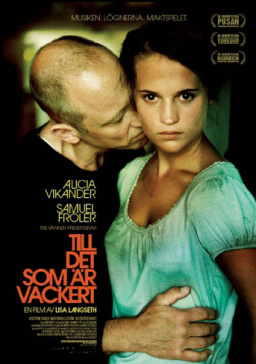

Pure (Sweden)

Another movie that thrives on wordless images and a powerful lead performance is Pure, from first time director Lisa Langseth. Alicia Vikander plays the central role of Katarina, born into the rotten side of her city, but a person with the knowledge that this is not all there has to be to her life. This story setup is a prototypical bildungsroman, at least until it isn’t. Of central importance in the movie is its music. Katarina finds an oasis and a yearning in the music of classical composers, seems drawn to the city’s orchestra, and so too is the movie inseparable from its soundtrack. Sounds move from diegetic to powerful renditions that envelop scenes, of which the symphony’s conductor (in the movie) emphasizes their intensity and speed. It is here we begin to see the acting of Vikander take shape. Playing a teenager can sometimes take on the appearance of not requiring much acting at all, but the jump from the normal scenes involving Katarina, her mother and her boyfriend to the elevated scenes in which she strives to find something, what exactly she does not know, through music is as sensational as what she hears. Vikander finds a precarious balance between innocence and ambition, not flip-flopping as the scenes dictate but finding a range of emotion within the two circles she moves in. From the verisimilitude of teenage arguments to the heightened intensity of where the story of Pure goes, Vikander never loses the audience, always is the anchor for the movie.

Another movie that thrives on wordless images and a powerful lead performance is Pure, from first time director Lisa Langseth. Alicia Vikander plays the central role of Katarina, born into the rotten side of her city, but a person with the knowledge that this is not all there has to be to her life. This story setup is a prototypical bildungsroman, at least until it isn’t. Of central importance in the movie is its music. Katarina finds an oasis and a yearning in the music of classical composers, seems drawn to the city’s orchestra, and so too is the movie inseparable from its soundtrack. Sounds move from diegetic to powerful renditions that envelop scenes, of which the symphony’s conductor (in the movie) emphasizes their intensity and speed. It is here we begin to see the acting of Vikander take shape. Playing a teenager can sometimes take on the appearance of not requiring much acting at all, but the jump from the normal scenes involving Katarina, her mother and her boyfriend to the elevated scenes in which she strives to find something, what exactly she does not know, through music is as sensational as what she hears. Vikander finds a precarious balance between innocence and ambition, not flip-flopping as the scenes dictate but finding a range of emotion within the two circles she moves in. From the verisimilitude of teenage arguments to the heightened intensity of where the story of Pure goes, Vikander never loses the audience, always is the anchor for the movie.

Langseth and cinematographer Simon Pramsten know how to make Katarina and her story relatable, even when her actions or situation is not, immersing the camera’s movements in her worldview, and showing a keen eye for framing her face. The familiar process of a new job is amplified through a repeated high angle, Vikander’s performance tentatively moving between innocence, enthusiasm and euphoria. The story and the characters are not new, but the involving work by director and actor turn Pure into something that nevertheless feels immediately fresh and is evidently well crafted.

One contentious issue following the screenings of Pure at VIFF was its ending, which be forewarned, will be discussed in the following paragraph. While the events of Katarina’s life turn messy, there is a tidiness to the proceedings of Pure that is undone by the ending. But this is not the movie going off the rails, or as one person put it, supporting immoral actions. The arresting following shots of the movie’s climax do not recur; though the camera puts the audience into her head, that is not where the film takes place. Pure lives in a world where actions and their repercussions do not end up nice and neat, and despite how unsatisfying to some the movie may turn, it does not condone, does not wrap up, does not compromise the world it has brought to our eyes. Its ending certainly does not negate all the good that came before in the movie, and neither does it erase what would happen after the final fade to black. For has she reached a destination? Pure refuses to have a clean, facile end to its story – its realistic world of class tensions and unknown futures not undone, but preserved as credible by its ending.

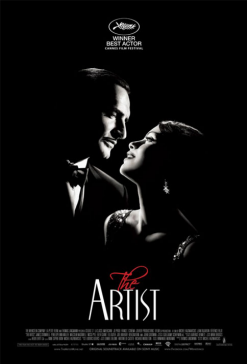

The Artist (France)

Based on its aesthetics, The Artist would appear to be a nostalgia piece, a nice bit of remembrance for those that know the times depicted in its black and white picture. And yes, The Artist’s tale of movies, depression, performance, and love is an entertaining one, but viewed in the context of VIFF this year, and seen on the day after news came out of the silent death of film camera production, it would do Michel Hazanavicius’s film a disservice to look at it only on its surface. Perhaps no scene in the movie is as beautiful as the one that takes place on a set of side-viewed stairs. Not one to attempt profundity in secret, the rising/falling connection is quite obvious. But aside from the movie’s plot, and aside from the movies’ past, this image, of one medium failing in its prime, for little reason other than the whims of executives who see only the value, not artistic, in what this change will bring, and audiences who see all the benefits of the new and forget the merits of the old, and another rising like a star, strikes at the heart of today’s debate, even as it shows the past’s. This is probably not the main purpose or premise of The Artist, which is perfectly delightful in its own right, but this coincidence of topic added a certain relevance to The Artist’s timeworn photographic memory.

Based on its aesthetics, The Artist would appear to be a nostalgia piece, a nice bit of remembrance for those that know the times depicted in its black and white picture. And yes, The Artist’s tale of movies, depression, performance, and love is an entertaining one, but viewed in the context of VIFF this year, and seen on the day after news came out of the silent death of film camera production, it would do Michel Hazanavicius’s film a disservice to look at it only on its surface. Perhaps no scene in the movie is as beautiful as the one that takes place on a set of side-viewed stairs. Not one to attempt profundity in secret, the rising/falling connection is quite obvious. But aside from the movie’s plot, and aside from the movies’ past, this image, of one medium failing in its prime, for little reason other than the whims of executives who see only the value, not artistic, in what this change will bring, and audiences who see all the benefits of the new and forget the merits of the old, and another rising like a star, strikes at the heart of today’s debate, even as it shows the past’s. This is probably not the main purpose or premise of The Artist, which is perfectly delightful in its own right, but this coincidence of topic added a certain relevance to The Artist’s timeworn photographic memory.

And what a memory it is. With a story that strikes at the real life highs and lows of the 1920s Hollywood actor and its silent conceit that works wonderfully when it comes to laughter, yet equally well is able to get at the humanity that is found and lost in performance, The Artist is both a pleasure to watch and a reminder of the fleeting nature of that pleasure. Jean Dujardin has received heaping amounts of praise for his part as the leading actor on three levels, and it is deserved, for he is able to not only pull off the role, but reflect the fact that this is a new movie dealing with an older time. Rather than attempt to mimic in every way a star of the time, he incorporates what makes silent acting work, the expression in every corner of the face, in his otherwise modern acting style. There is no silly playacting mimicry here: even when an actual clip of an actor bearing a certain resemblance to his character turns up, we see the facial similarity, but don’t recognize the tortured commitment Dujardin brings to the movie. And the supporting actors, both American and French, bring the same approach to their roles, embodying the characters of a producer, a co-star, and so on, without being tied down to one influence. They take a part from the past and allow it to exist in the present.

This level of commitment to making a movie set in a time period, and true to that time period, yet not copying its every frame, frees The Artist from trying to be something it isn’t: a movie from the 1920s, and allows it to be what it actually is: a fine movie from 2011.