By Vanessa Broadbent (The Cascade/Photos) – Email

Print Edition: January 14, 2015

We’ve all heard the horror stories of Canadian residential schools, but for most of us, that’s it. We’ve only heard about them. We don’t know enough about them to truly understand what happened, and we certainly don’t know enough to understand why this is such an important issue for Canadians.

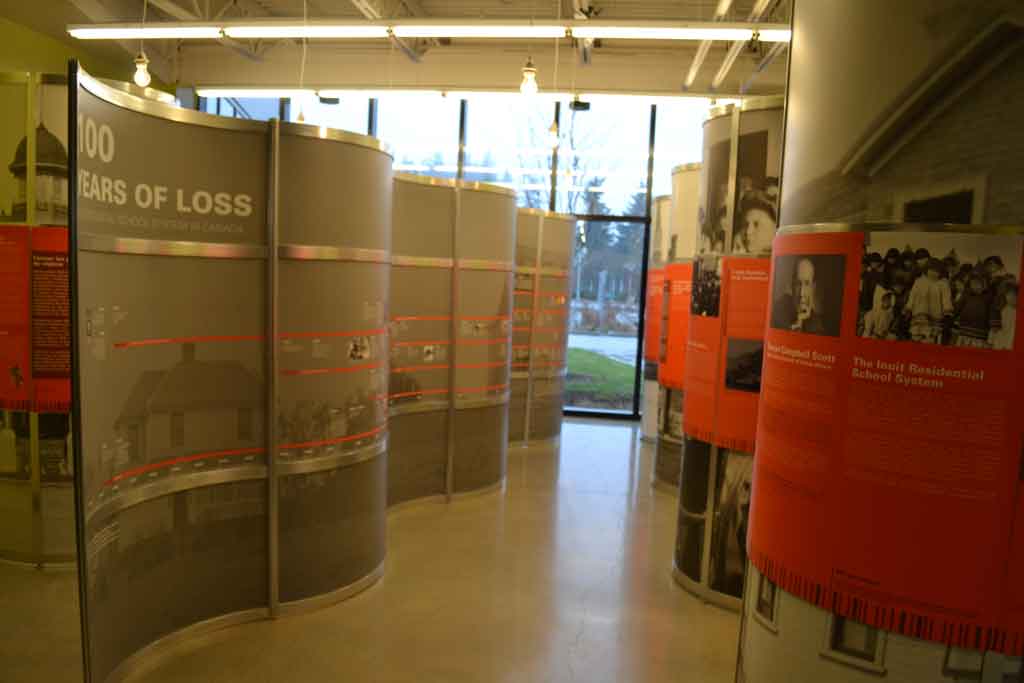

That’s why the Reach Gallery Museum and the Legacy of Hope Foundation opened a new exhibition, 100 Years of Loss — The Residential School System in Canada, on Saturday. The gallery focuses on the history of residential schools, from their formation in the early 1830s to the closure of the last school in 1996, and their impact on Aboriginal Peoples of Canada. The exhibition is targeted toward non-Aboriginal Canadians, with the goal of making it clear why these issues matter to all Canadians, not just those who were directly involved.

Although the exhibition had a disclaimer at the beginning stating that some of the subject matter may be disturbing for some audiences, it was no preparation for what was to come. It’s not that the stories were graphically retold, or that the photographs showed disturbing images. The most disturbing thing was that this was perpetrated in Canada, by Canadians.

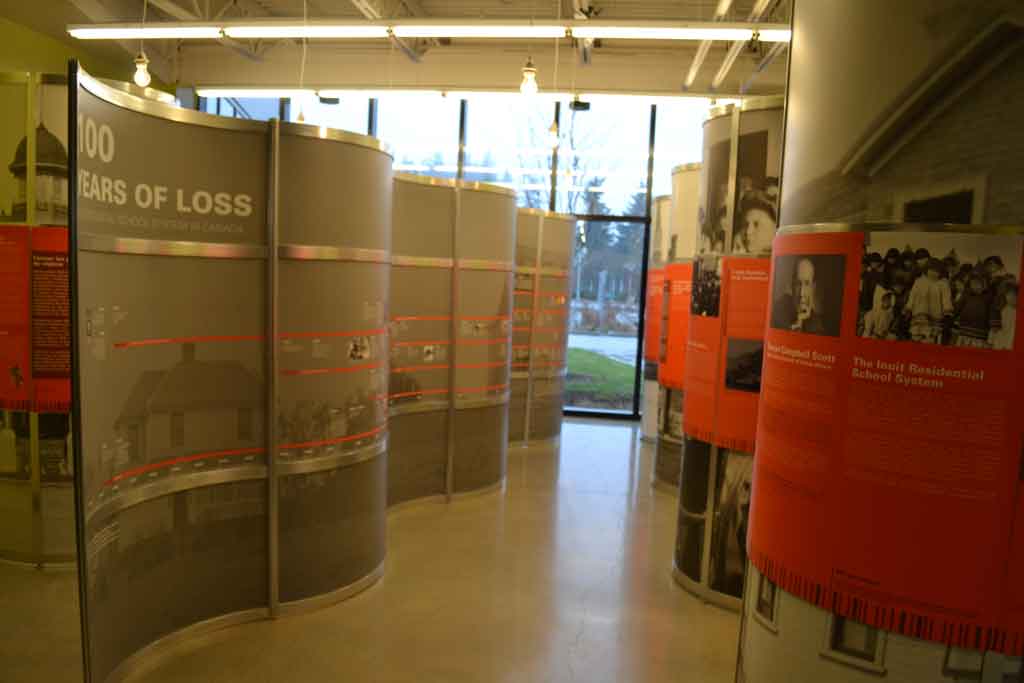

The exhibition is divided into two sides, one in French and the other in English. Each side had four columns, each focusing on a different aspect of residential school history. The two sides were divided by a long, winding timeline of the history of the residential schools. The timeline started with the formation of the first school, and ended with Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s apology to the Aboriginal People involved, as well as the implementation of the Common Experience Payment — a component of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement — to compensate those involved.

The first column focused on the history of residential schools and how they started in Canada. It featured excerpts of letters from Canadian officials, including one from Duncan Campbell Scott, the deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs at the time, stating that he understood that the conditions on residential schools were resulting in deaths among children, but it did not require “a change in policy.”

The second column focused on what actually happened in the residential schools. A combination of photos and stories told about various things that aboriginal children had to endure, including physical and sexual abuse as well as neglect and malnutrition. There were stories of children running away from the schools to go home to their families, as well as families coming to the schools after learning about the conditions and trying to take their children home.

The third column explained why residential schools are still a current issue in Canada, even though they have finally all closed. It stated that although the Canadian government is now compensating those who attended the schools, many Aboriginal people are still unable to receive compensation because they can’t prove that they attended a school. Records of many children, especially Métis, do not exist or are incomplete, and therefore cannot be proven.

The final and fourth column in the exhibition explained to viewers “why it should matter to a Canadian who never attended a residential school.” Reasons included that Aboriginal communities have similar levels of poverty, illness, and illiteracy as in developing nations. It explained that this part of Canadian history is now the responsibility of all Canadians, not only those that were involved. It read, “We must see the legacy of the schools in our streets and communities every day. We must all commit ourselves to a process of reconciliation and healing.”

An afternoon of exploring the graphic history of residential schools can put quite the damper on one’s day, and all though the horrors can’t be erased, you’ll leave the exhibit knowing that there’s still something you can do about it. Raising awareness is key, and it’s suggested that viewers get in contact with local aboriginal groups and encourage others to do the same.