On Oct. 18, the UFV Centre for Sustainability, along with volunteers, conducted the third annual waste audit. Each year, the centre collects more data, and uses it to inform UFV’s waste disposal system.

“What we would do is take one day’s worth of garbage waste from A and B buildings, pile it up on the Green, then rummage through it and put it in different piles,” UFV Energy Manager, Blaire McFarlane, said. “[Then we] look at what was found in the landfill bin, how many items and in what percentage should be in recyclables, what should be in compost, which was miscellaneous glass or styrofoam.”

Travis Gingerich, a UFV geography student and sustainability coordinator assistant, also participated in the audit. His work has been instrumental in the development of the waste collection system.

“Basically, the goal of the waste audit is to assess the effectiveness of our waste collections systems on campus,” said Gingerich. “With the rollout of our sustainable waste stations this year, it was especially important to do the audit and assess the success, as well as find the areas we still need to tweak and find tune.”

Results from the 2015 audit found that a lot of plastics ended up in the garbage, rather than recycling. Using that data, the UFV Centre for Sustainability started a new recycling program. The impact was tangible, it reduced mixed recycling previously going into the garbage by 25 per cent.

In 2016, the audit found that the amount of organic compostables in the garbage actually increased. This came as somewhat of a surprise.

“We recognized as a department that we needed fundamental change, and those results spurred on this project of the sustainable waste stations,” said McFarlane.

That project led to September’s implementation of the four-bin system: Landfill, refundable beverage containers, mixed recycling, and organics.

This year, the auditors examined all four of the new waste streams. While it’s the first audit for the new system, which means there isn’t directly comparable data from previous years, what was found showed an improvement in proper waste disposal.

What led up to the new system?

The UFV Centre for Sustainability conducts research, collects data, and works to make UFV a more environmentally sustainable institution. Over the years, the centre has led multiple initiatives that focus on reducing negative environmental impact. In September, the four-bin waste system was employed across campus.

“We’ve been trying to implement a decent recycling program for the last decade,” said David Shayler, associate director of operations.

Several years ago, facilities decided to take garbage cans out of single-occupant offices. Shortly after that, they created the “bin-be-gone” program, which continued to remove bins, placing an emphasis on centralized waste bin locations.

“There was some resistance, but we pioneered through that, and the majority of faculty and staff adhere to our new policies.”

Shayler said they had janitorial staff going into offices every second day to pull out garbage bags. It resulted in thousands of bags each week heading to the landfill. Most times, the garbage containers only had a few pieces of paper in them. The change meant far fewer plastic bags alone would end up in the landfill.

“Now that the towns and cities are doing the same things, where you have to separate your garbage at home, it makes it easier for us to pass on that educational message to people,” said Shayler. “We say, ‘Come on, you’re responsible at home, be responsible at work and separate your waste accordingly, and we’ll give you all options that you need.’”

Before the four-bin system, mixed recycling and refundable beverage container bins were available, but their placement was somewhat sporadic, according to Gingerich. Not as much thought went into their placement as with the new system, which is actually quite comprehensive.

In fact, far more work went into the placement of the bins than you might think. Gingerich, for his GIS certificate capstone project, built a program that used different spatial indicators to optimize waste bin placement.

“Some of those indicators we looked at were proximity to classrooms, for one thing, [and] the size of those classrooms too, so a large classroom is going to have more people coming out of it,” he said. “The whole concept that we worked with was waste production potential. How much waste is a specific space going to produce?”

The first step in optimizing bin placement was to identify key spaces for waste production potential (WPP). Classrooms have a high WPP; common seating areas have a high WPP. Once they collected that data, the team developed a map of UFV that showed clustered hotspots for waste production.

From there, Gingerich said they looked to optimize placement in terms of line of sight and buffer creation. You’ll find that you never need to walk more than 20 metres to get to a waste station, anywhere within a corridor.

“So, if you walk out of the classroom, you should have a waste station within sight,” said Gingerich.

Where does the waste go?

UFV has a general landfill dumpster, organics bin, and multiple recycling bins. But most waste isn’t processed at UFV, so it’s important that each type of waste ends up in its proper stream, ie. the right bin.

Garbage waste first gets compacted here in Abbotsford, then sent across the border to the U.S., where it likely ends up at the Roosevelt Landfill. Roosevelt does run an electricity generation plant off of the emitted methane gas, but this is still the least efficient way to dispose of waste — especially waste that could serve a better purpose, like cans sent to a bottle depot, or food waste to a composter.

Refundable beverage containers are collected by Pacific Pathways, an organization that provides support for intellectually disabled persons. The proceeds earned through returns goes to the Pathways participants, who collect refundables bi-weekly.

Mixed recycling (cardboard, paper, glass) is bailed and shipped to China — hardly the most environmentally friendly option.

And finally, compostable organics are transported to The Answer or Enviro-Smart, in Abbotsford and Delta, respectively. Once processed, these organics are repurposed as topsoil. This is by far the best option for waste. Transport costs are minimal, and it becomes reusable. This means that absolutely everything that can be composted should be composted.

While there is a compost system at CEP, it’s relatively small, and better suited for paper towel or the food scraps produced by the CEP’s culinary program — things that break down easily. Actually, most composting systems like that of a backyard compost aren’t capable of composting a lot of UFV’s organics. You’ll see “PLA” on the bottom of a lot of the cold beverage cups coming out of any food service establishment on campus. PLA, polylactic acid (fermented plant starch), which looks and feels like plastic, is what all the utensils and cups at UFV’s food services are made up of. It’s compostable, but only under certain circumstances.

According to Scientific America, PLA is technically “carbon neutral” because it’s made from renewable, carbon-absorbing plants rather than petroleum-based plastics. It also doesn’t emit toxic fumes when incinerated, another plus.

The trouble with PLA is, in order for it to break down, it requires a heat that can’t be generated in a backyard bin. For PLA to break back down to its constituent parts (carbon dioxide and water), it needs to reach temperatures in excess of 60°C. If the compost doesn’t reach that temperature, those forks and cups won’t break down.

“Analysts estimate that a PLA bottle could take anywhere from 100 to 1,000 years to decompose in a landfill,” according to Scientific America. Though it’s far friendlier than traditional petroleum-based plastics, it still needs to find its way to an industrial compost facility, where higher temperatures are reached.

“They do decompose, but for one thing we’re not getting the benefit of being able to reuse those substances for soil formation to get it back into the food cycle,” Gingerich said. “Secondly, they will decompose in a different way. They’ll decompose anaerobically as opposed to aerobically.”

Aerobic decomposition produces carbon dioxide, anaerobic decomposition produce the far more harmful greenhouse gas, methane.

This is why, Gingerich said, the Centre for Sustainability is stressing the importance of placing waste in the right bin. PLA may not be as bad as petroleum-based plastics in the landfill, but it certainly won’t reach its full potential there.

‘The Audit Results’

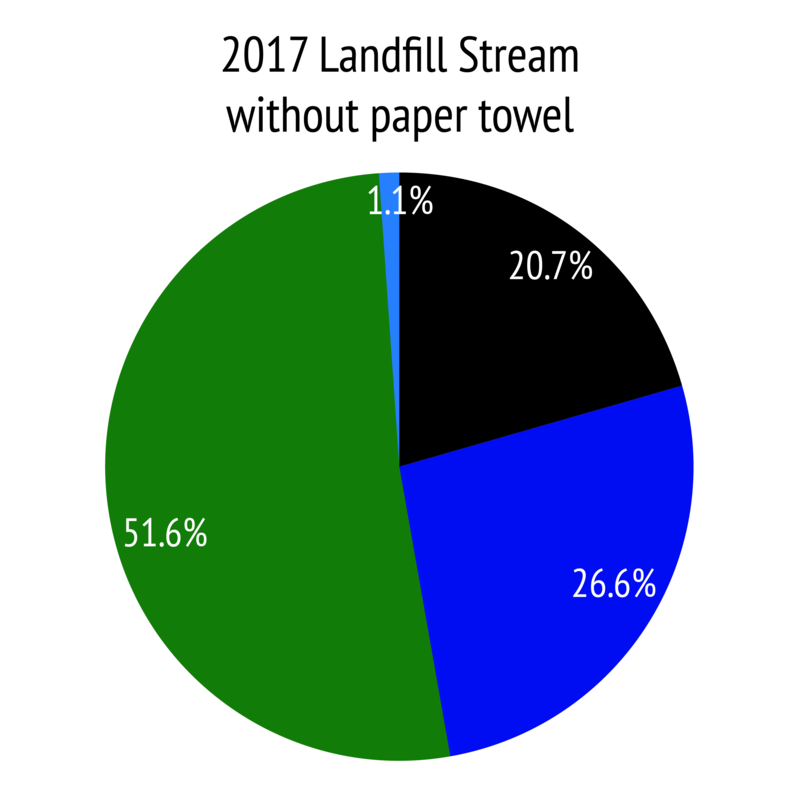

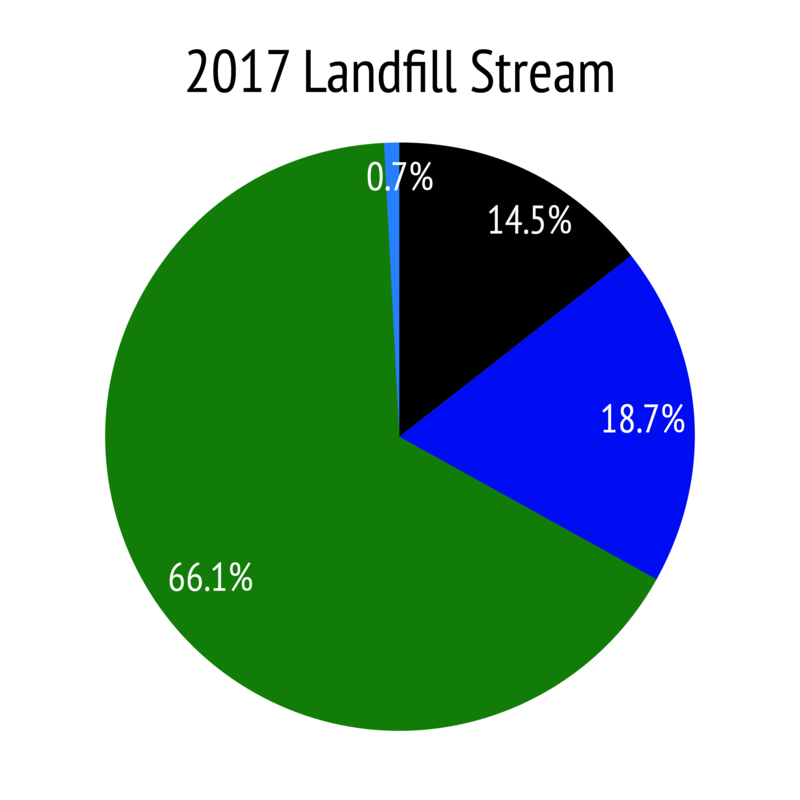

In the past, success was gauged based on how much true waste ended up in the landfill bin. Although there are now four waste streams to audit, comparing previous years’ results to this year’s brings a focus to the landfill stream.

In terms of landfill waste, this year actually saw a decrease in compliance. Since last year, true waste in garbage bins dropped 40 per cent. Why? Likely paper towel, which is technically an organic compostable. Some garbage bags found in the waste audit contained almost exclusively paper towel.

Since the audit, signs have been placed in bathrooms to inform users that these bins are for paper towels only. But even if the paper towel is factored out of the results, 50 per cent of garbage was made up of organics.

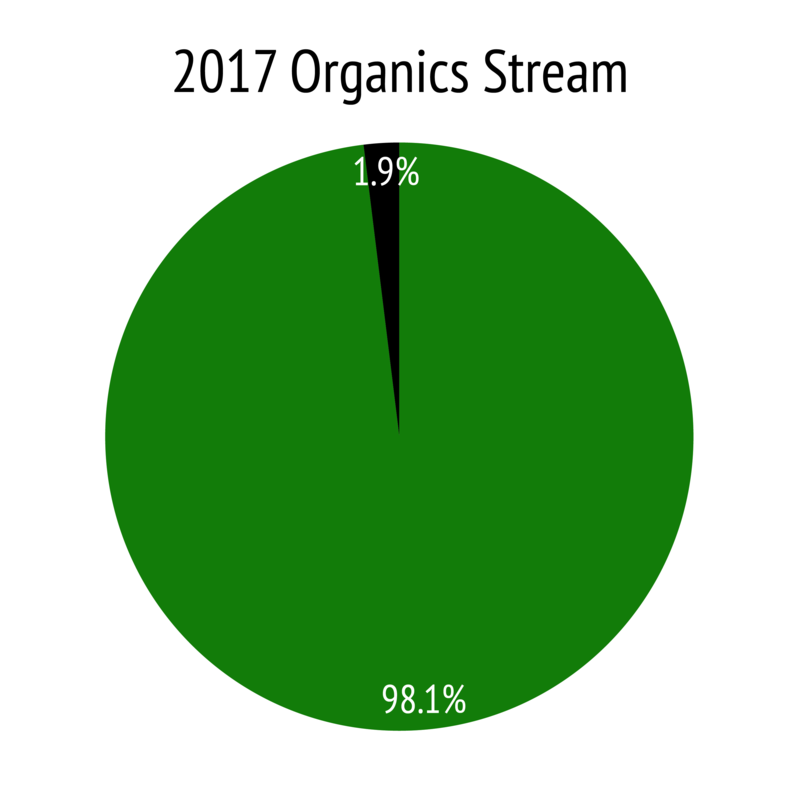

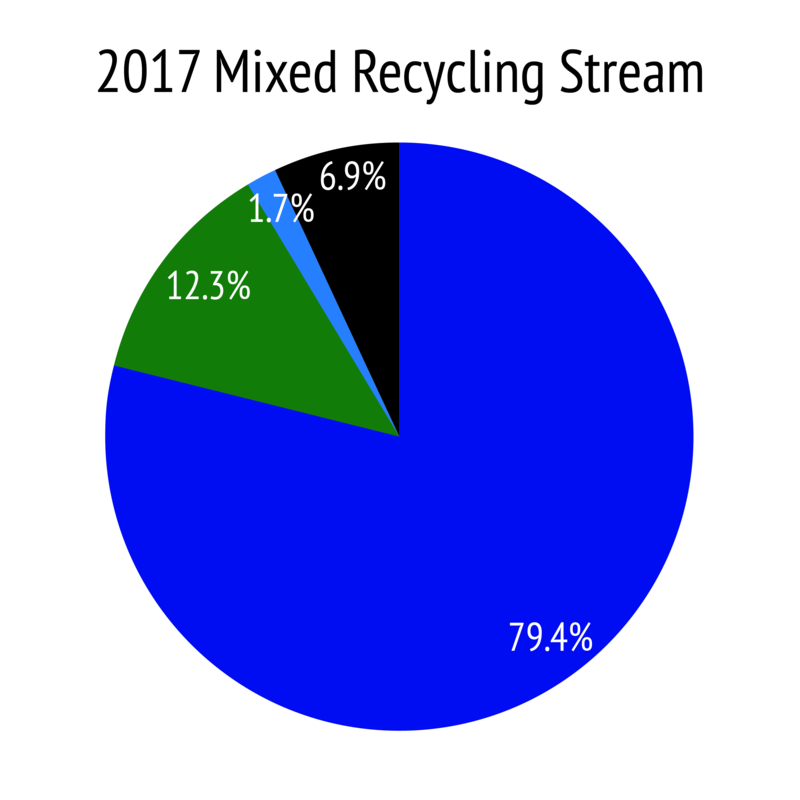

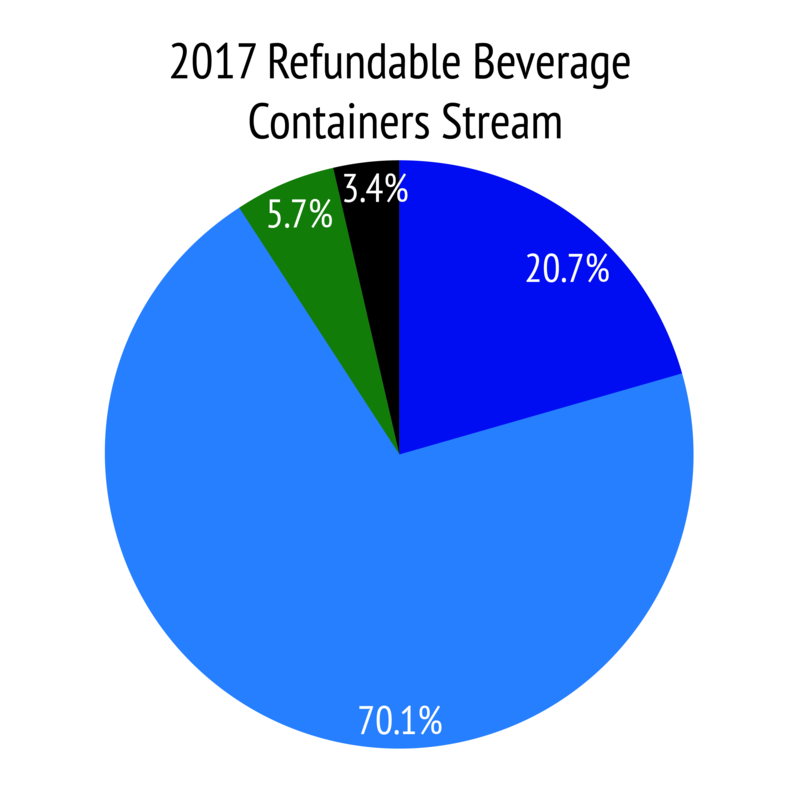

Refundable beverage containers, mixed recycling, and organics, saw a 70 per cent, 79 per cent, and 98 per cent compliance with proper disposal, respectively.

In the refundable beverage container waste stream, the biggest issue is the inclusion of coffee cups. Perhaps people see the round hole and associate it with their cylindrical cups. The problem with this is cups from Tim Hortons or Starbucks are considered mixed recycling; cups from UFV food services are PLA compostables. Either way, too many of them end up in the refundables bin.

The mixed recycling bins saw fairly good results. Still, organics composed a majority of the non-mixed recycling waste in the stream. Again, probably because of a lack of education regarding which types of containers are compostable, and which are recyclables.

Organics saw an incredible, nearly perfect, compliance. Gingerich said they were surprised at how successful this stream has proven to be.

Making sense of the data:

Though it’s difficult to compare the multi-year data directly, each audited waste stream provides insight into how UFV’s waste is disposed.

“We can draw some comparisons between landfill streams of years passed and this landfill stream,” said Gingerich. “But if you’re looking at, for example, total amount going to the landfill, that sort of thing, it’s really tough to compare apples to apples here, just because there has been such a drastic change.”

What can be determined, more or less, is how much the additional three bins contribute to the reduction of non-garbage waste in the landfill stream. And, as indicated by the audit, 50 per cent of non-true waste was diverted to other waste streams — this is a massive improvement.

“What we did see in this waste audit is a lot of the organics are going into the landfill container, rather than going into our organics container,” said Gingerich. “It was probably the biggest surprise, and also the largest area that we recognize. There either needs to be greater education, more effective signage, or some other method of getting that point across.”

“There’s a few questions there around what it could be. It could be an education component,” said Gingerich. “We have decided to put lids on the organic containers just to reduce the smell, but that could deter people from opening it up to throw their organic waste out.”

Moving forward with the sustainable waste program, Gingerich said the centre will continue to refine the system. Though the four-bin system has proven to be beneficial for sustainable waste disposal, improvements can be made. The data collected during the audit doesn’t necessarily show why people choose to put waste in the wrong bins, but it does suggest that more can be done. With more education and signage, Gingerich hopes to see an improvement each year.

“Everyone interacts with waste, there’s no one on campus who won’t approach these bins at some point in their day, most likely,” McFarlane said. “So, it affects everyone in some capacity, and everyone is capable of making a significant change for the university.”