By Valerie Franklin (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: March 25, 2015

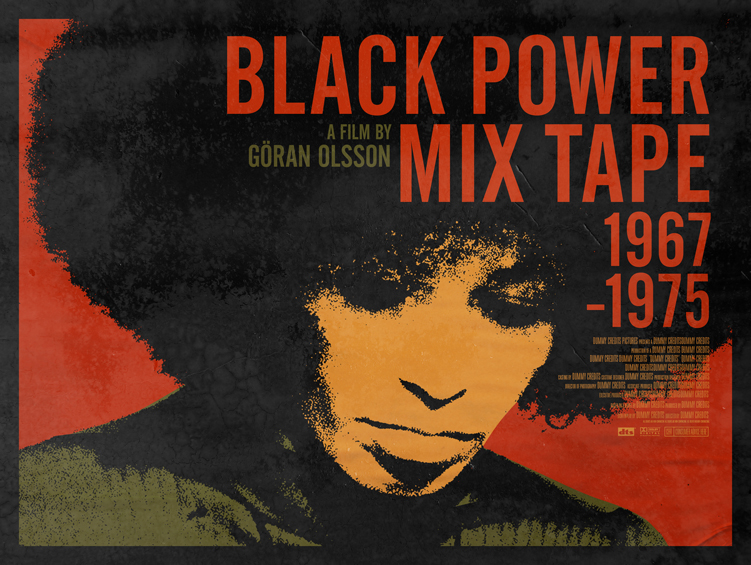

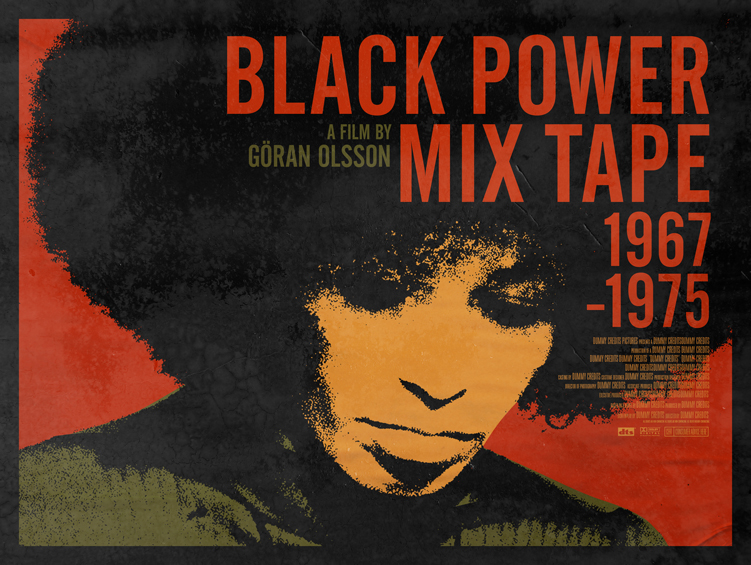

Students and faculty filled B121 on March 19 to view The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975, a documentary following the rise of the black power movement in response to segregation, police brutality, poverty, and other social ills. The film was shown as the final installment of the Slavery, Race, and Civil Rights in the Americas film series presented by the history department, hosted by professors Ian Rocksborough-Smith and Geoffrey Spurling.

Presented in nine chapters, The Black Power Mixtape is a collage of footage shot by Swedish journalists in the US between 1967 and 1975. The recordings were forgotten in the basement of Swedish Television until they were found 30 years later, and modern filmmakers stitched the footage into a documentary. Directed by Göran Olsson, the film overlays black and white footage from the 1970s with commentary from modern-day civil rights activists such as rapper Talib Kweli, singer Harry Belafonte, and professor Angela Davis, who appears in both the 40-year-old footage and the present-day audio commentary.

“The story of black power in America is one that often ends tragically through the mid-to-late ‘60s,” notes Rocksborough-Smith. The documentary surveys some of the most powerful events of those nine years, including the Vietnam War, Davis’ unjust incarceration and murder trial, the Attica Prison revolt, and the deliberate introduction of heroin to African-American communities as a method of controlling the rebellious population. Above all, the targeted assassinations of high-profile leaders who had expressed support for civil rights, particularly Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and the Kennedy brothers, sparked a furious revolution in the black communities of America.

The formation of the Black Panther Party (BPP), originally called the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, provided a radical and violent counterpoint to Martin Luther King’s pacifist approach to civil disobedience. Stokely Carmichael, a formerly nonviolent activist who took up a more militant philosophy and became the “prime minister” of the BPP, features largely in the film.

“In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience,” Carmichael says bluntly. “The United States has none.”

Angela Davis, a young professor, socialist, and civil rights activist in the 1970s, was arrested and almost sentenced to death after her gun was used in the armed takeover of a courtroom, even though she was not involved in the crime. She describes living under perpetual scrutiny and prejudice as a black woman, including being frequently stopped by police for no apparent reason. Although she doesn’t condone violence, she acknowledges that the violent philosophy of the BPP was a frustrated response to this culture of abuse — a means to an end.

“When you talk about a revolution, most people think ‘violence’ without realizing that the real content of any kind of revolutionary thrust lies in the principles and the goals that you’re striving for, not in the ways you reach them,” she says.

But African-American professor Robin Kelley, a modern-day civil rights activist, notes that the black power movement wasn’t just about racial violence; it built a foundation for the modern incarnation of the civil rights movement.

“I always think of [the black power movement] as three different movements, three different legacies,” he says: building black institutions and supporting black business, but not necessarily in a revolutionary capacity; cultural nationalism, which can be seen in black communities’ enthusiastic responses to films like Malcolm X; and the black radical tradition, which exists in some forms of hip-hop and modern counter-cultural organizations.

The film’s Swedish point of view offers an unexpectedly intimate perspective of the American racial conflict, presenting the story from the eyes of outsiders.

“For me to have lived through and seen this through my young eyes in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, but then to see it all through the eyes of a Swedish crew, it’s even more fascinating,” says Kelley in the film. “There’s a sense of innocence that I think is evident, but yet it’s not really an innocence as much as it is also a global perspective.”

Rocksborough-Smith points out that although modern America may have a black president, conditions are in many ways no better today than they were 40 years ago, including the startling overrepresentation of people of colour in the prison system. As racial tensions continue to rise today in response to police brutality in Ferguson and elsewhere in the United States, it becomes more important than ever to continue to document inequality so it can be faced and challenged.

“We have to write and document our history right now,” says modern-day musician Erykah Badu in a voice over.

“It’s really not about black and white — it’s about the story.”