By Dessa Bayrock (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: April 2, 2014

There are some things you can never know enough about, which is why this week’s column is a collection of things you probably didn’t know about everyone’s favourite cephalopod — the squid.

Squid are difficult to study; where other sea life can be kept and observed in aquariums, the squid’s natural habitat is the open ocean. Living quarters for an octopus can be recreated fairly easily, since octopods like to hang out in rocky outcroppings and cave areas. Translating miles of open ocean into an enclosure for squids, however, is a different story altogether.

But while it’s pretty much impossible to study squid in captivity, researchers are slowly building a wealth of facts and figures from watching squid in the wild.

The colossal squid

Disproportionate creature of the deep

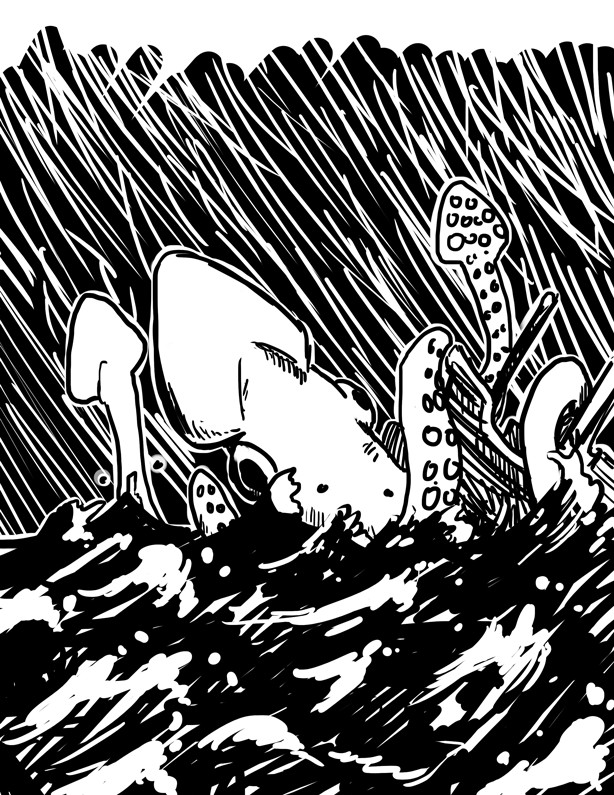

The giant squid is known for being, well, giant. But what do you name a squid species that’s larger than the giant squid?

Meet the colossal squid, or Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni.

It’s one of the rarest species of squid on the planet, and only six specimens have ever been caught. Researchers estimate it can grow up to 45 feet long, which is just a little shorter than a school bus. However, most specimens are only a couple meters long; a particularly large one caught in Antarctica in 2007 measured about 30 feet from top to tent

acle.

The colossal squid is actually about the same length as a giant squid, and the colossal’s tentacles actually clock in a little shorter than the giant squid’s. The squid earns its title for its giant, giant top half — the fleshy part of the squid, known as the mantle, which is two to three times heavier than the corresponding part on the giant squid.

But like most alarmingly enormous animals, the colossal squid is a gentle giant — and with a bulbous, disproportionate body, it’s more of a comical sidekick of the deep than a monster.

Excellent eyes

It’s not the size that counts … or is it?

Squid lay claim to the largest eyes on the planet; the colossal squid beats the blue whale by a fair margin. Even the eyes of smaller squid are quite large; the Humboldt squid’s eyes are the size and shape of cupcakes.

But the size of squid eyes has, until recently, confused researchers; theoretically, a squid shouldn’t need eyes bigger than an orange to see prey, even in extreme low-light situations. After having a chance to study the eyes of a colossal squid, however, researcher Dan-Eric Nilsson at Lund University in Sweden says the eyes might be designed to track predators, not prey. The larger eye is designed not only to see food nearby, but also large and far-away objects — such as the sperm whale, one of the squid’s main predators.

But perhaps coolest of all, squid eyes have no blind spot — unlike human eyes, where the optic nerve creates a visionless spot that the brain fills in automatically. Squid don’t have that problem; their optic nerves are organized differently, meaning they can see everything without the brain having to fill in the gaps.

The squid rocket

It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a squid?

Squid move around their ocean habitat using what is basically jet propulsion; they suck water in and shoot it out to cruise around.

But it’s only one short evolution from jet power to rocket power, as squid seem to have realized; many species not only jet themselves through the water, but can jet themselves above the surface and take short flights through the air.

The orangeback flying squid (as the name may suggest) has mastered this skill; at two-and-a-half inches in length, it can launch itself out of the water for several feet of flight at a time and hit speeds of five miles an hour.

There are several reasons squid may choose flight instead of simply swimming around. First of all, it can make for a clever and unexpected escape if a squid is being chased by a predator. It also takes less effort to move through the air than through the water — the squid can save about 20 per cent of its energy by taking to the surface.

Finally, as Dr. Craig McClain of Deep Sea News suggests, maybe squid just have a grand old time doing it.

“Who wouldn’t want to be a rocket?” he says. “Why be an astronaut when you can be a rocket?”