By Katie Stobbart (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: February 25, 2015

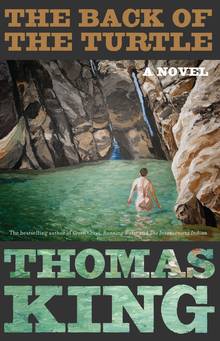

“Showcasing King’s brilliant wit and trademark wordplay, The Back of the Turtle is a funny, smart, sometimes confounding, and altogether unforgettable tale of betrayal, salvation, and the resilience of life.”

The promises made by anonymous book jacket writers are most often doomed to be broken. Thomas King’s latest novel, however, which appears after a decade-long post-Green Grass, Running Water sabbatical from the genre, lives up to the hype.

While The Back of the Turtle was written true to King’s signature comedic style, a sense of growing immediacy makes it more intense than his last novel. His commentary on corporate thinking, consumerism, and environmental catastrophe, among other contemporary albatrosses, cuts in with a sharper edge.

Dorian, CEO of a fictional corporation called Domidion — which is responsible for a slew of oil spills and devastating chemical pollution — often articulates that commentary within the narrative, followed by a note, of course, that he’d never share those thoughts with the media.

“It was all a waste of time. North American Norm didn’t give a damn about the environment. Cancel a favourite television show. Slap another tax on cigarettes. Stop serving beer at baseball and hockey games. That was serious.

“Spoil a river somewhere in Humdrum, Alberta? Good luck getting Norm off the sofa.”

That said, King’s most effective method of conveying a sense of horror — at what has been done, what we have done to the world we live in and rely on — is through his depiction of setting. The novel takes place in two central locations: a nearly vacant ocean-side town in British Columbia whose environs and economy were decimated by human interference, and the sleek, fast-paced metropolis of Toronto.

At the start of the novel, it seems to be set sometime in the future. The contrast between the two distinct milieux, coupled with the ever-present steel of reality as the sanctity of Canada’s wilderness appears to teeter, invokes a sense of horror in the reader, an internal plea for a way to slam the brakes before this really happens, before —

It’s too late. As the novel progresses, it becomes clearer that not only have the dominoes already been set to falling, the flat-line is only a hairsbreadth from the present. To an extent, such a narrative seems to forget survival and flirts with a seething unrest reliant on the inevitability of destruction.

It’s a good way to spark a panicked reaction in the reader, a sudden need to be aware of what’s really happening, a desperation to find the key to a way out. Is there one?

Aha! King shouts. See, that’s exactly the reaction you should have. There’s the key: engage. But anyone who has tried to push for engagement knows that is easiest said, and the frustration of a society that expends considerable energy convincing Norm to stay on that sofa.

It’s possible that frustration will not be assuaged. Instead of its end, King offers a frustratingly tenuous resolution to the Big Problems raised in the novel. The threat is still out there; the dark beast’s slouching away from the spoiled garden is only temporary. Maybe it is too late. Maybe there’s nothing you can do but live as mindfully as you can in your small, remote humanness, hopeful for community and for the return to Paradise.

That is the sliver of hope: resilience. Maybe we survive after all. The question up for debate, however: is that a good thing?