by Chelsea Thornton (Staff Writer)

Email: paul at ufvcascade dot ca

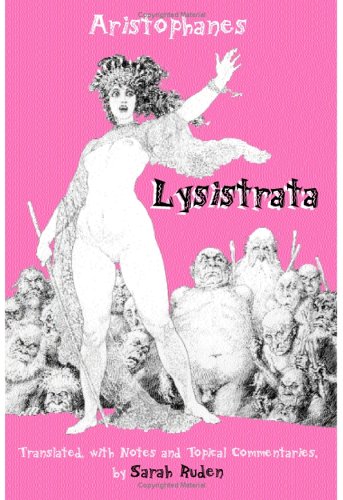

I’ll admit, what drew me to this translation of Lysistrata was the cover: hot pink, block letters, trolls, and nudity don’t often find themselves gracing the cover of ancient classics.

I’ll admit, what drew me to this translation of Lysistrata was the cover: hot pink, block letters, trolls, and nudity don’t often find themselves gracing the cover of ancient classics.

The unusual cover is not, however, a random grab for attention. The vivacity of the cover is matched by the playfulness of this translation. As translator Sarah Ruden explains in the preface, most available translations of the comedy do not capture the plays raunchy spirit: “The play was raunchy enough, but somehow heavy and prim too, and not particularly amusing.” The difficulty arises from the fact that many jokes are literally lost in translation; ancient Greek and modern English are two very different languages. So in Ruden’s translation, she admits to straying away from a perfect direct translation in favour of a translation that captures the feeling of the play in Greek. The lightness with which she infuses the play runs throughout the preface and historical notes as well.

The result of Ruden’s efforts is a fitting linguistic stage for one of Aristophanes’ best known comedies. Whether or not you think you’ve heard of it, you have definitely experienced the fall-out. It may be the first recorded instance of women withholding sex in order to get their way.

Essentially, the women of Athens are sick of the seemingly endless Peloponnesian Wars. Led by the “good-looking young matron” Lysistrata, they ally themselves with the women of Sparta and decide to abandon their husbands beds until the war is brought to an end. Meanwhile, in support of the younger women, the older women seize the Acropolis and the treasury held within. The men are forced to face a war without funding or womanly comfort. Before long, a Spartan envoy arrives in Athens to seek peace, and the women triumph.

I promise, this is not the kind of Greek play you might typically come across in the classroom. Almost every line is structured around some sexual pun or poorly veiled innuendo. In the opening scene, Lysistra attempts to convey the importance of her plan to her friend:

Calonice: Precious, what is eating you?

Why summon us in this mysterious way?

What is it? Is it … big?

Lysistrata: Of course.

Calonice: And hard?

Lysistrata: Count on it.

Calonice: Then how could they not have come?

Lysistrata: Shut your mouth. They would have flocked for that.

The exchange between the two women reveals one of the central sources of comedy within the play. Although the men suffer from the denial of sex, the women do too, and Lysistrata needs to work hard to get them to agree and stick to her plan. The contrast of their noble aims and their baser drives ensures the play comes across as comedic instead of moralizing.

This translation of Lysistrata’s greatest strength is its universal appeal: whether you read it because of the play’s position in literary history or for a raunchy good time, you will not be disappointed.